First ministers questions: government accused on justice reform

- Published

There he sat, silent and lugubrious. All around him, his accusers demanded his head - or at least a stiff sentence of community work.

His name? Kenny MacAskill. His designation? Justice secretary. His crime? Steering a piece of Scottish government legislation through a decidedly sceptical chamber.

There is, of course, more to it than that.

The legislation in question includes the abolition of the general requirement in Scots Law for there to be corroboration - at least two items of evidence - before a case can go to court.

Supporters of the change say the rule prevents prosecution in certain cases - such as domestic abuse or sexual violence - where corroboration is difficult.

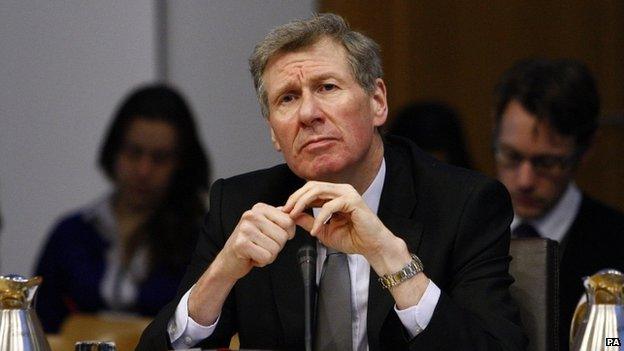

Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill's handling of legal reforms was questioned by opposition MSPs

Critics of the change, including senior figures in the legal profession, say that the rule also prevents miscarriages of justice.

Said critics were less than assuaged by what they regarded as an inappropriate tone adopted by the justice secretary when the bill was agreed at stage one.

He had suggested, inter alia, that his opponents were using the issue as a surrogate for attacking the SNP and the cause of independence.

In questioning the first minister, both Ruth Davidson of the Tories and Willie Rennie of the Liberal Democrats lengthened the charge sheet.

They asked MSPs also to consider issues such as the closure of police stations and courts.

In essence, they were inviting the first minister to condemn his own minister. This he would not do.

Tax talk

On policing, he said that officer numbers were up and crime down. On corroboration, he said that the reform was widely welcomed by victims' groups.

Further, he referred members to the expert group set up under the chairmanship of Lord Bonomy which is to look at additional safeguards which might forestall concerns about miscarriages.

Until those safeguards are in place, corroboration would remain.

But, in the interim, Parliament is being asked to endorse the legislation which would enable corroboration to be scrapped.

Mr Salmond was quizzed over his policy on the return of the 50p tax rate

Anxious critics think this is the wrong way round. They think it is "sentence first, verdict afterwards" - to borrow from that astute political analyst, Lewis Carroll.

More to come on that. But, on the day, Mr Salmond defended his justice secretary or, more narrowly, the justice system over which he presides, politically at least.

Earlier, Mr Salmond and his Labour interlocutor, Johann Lamont, traded tax talk. In the event of independence, she asked, would the FM seek to return the top rate of income tax to 50p?

Mr Salmond did not answer that precise question, preferring instead to refer to his party's record in the Commons.

In 2012, he noted, the SNP had tabled opposition to the plan to cut the rate from 50 to 45 - with minimal support from Labour at the time.

Labour power

More generally, he backed the principle that, with a deficit persisting, it was wrong to reward the relatively rich with a tax cut.

Ms Lamont tried again, pointing out that earlier in the week Mr Salmond had indicated that he would not wish Scotland to be at a tax disadvantage compared to the remainder of the UK, rUK.

That, she argued, implied he would not want to increase the upper rate solely in Scotland.

Then the lesson. Given the FM backed a cut in corporation tax for Scotland - to attract investment - did that not leave him "out Torying the Tories"?

Mr Salmond noted that Labour had held UK power for 13 years - but had reduced the top tax rate for just 36 days of that period.

Independence would give Scotland control over all taxation - plus issues like childcare and free school meals (core offers in the White Paper, external.)