Scottish independence: Where does the power lie?

- Published

Johann Lamont said Labour would the new plan in its manifesto

At the end of the launch in Edinburgh, Johann Lamont seemed content. Indeed, she confided that she had rather enjoyed the event.

Which is perhaps contrary to expectations when you recall the controversy which assailed her and the Labour Party exactly a year ago.

Remember that? The interim report from Labour's commission on devolution reported to the party conference in Perth.

At the time, the commissioners were "minded" to devolve the whole of income tax to Holyrood and to devolve Air Passenger Duty.

Cue angry row at the conference as various fretful MPs warned that this was a step - indeed a giant leap - too far.

Now the Labour package devolves 15p worth of income tax at all rates - with an added power to top up the higher rates in the pursuit of redistribution.

Other taxes remain at Westminster - but certain welfare elements such as housing benefit and attendance allowance are devolved. Local government gets added clout.

Timid package

So what has happened? Two interpretations offer themselves.

One, Labour has achieved a pragmatic settlement after, to borrow Ms Lamont's description, "wrestling" with the competing desires to maintain the Union and strengthen Scotland's fiscal powers. (Copyright, J. Lamont)

Two, Labour has retreated in the face of Westminster complaints. This is a timid package even by contrast with the interim version. In an internal power battle, the MPs have won. (Copyright, A. Salmond)

It is, of course, up to the voters to judge between these alternative verdicts. However, it is possible to discern a few other factors in play.

Firstly, the orchestration of this year's effort has been deft. In particular, key Westminster figures - Jim Murphy, Douglas Alexander and, above all, Gordon Brown - have played a role in stressing the need for change allied to a narrative of helping the poorest.

Former PM Gordon Brown has already set out his thinking on the future of devolution

This plucked certain Labour chords - while reminding potential dissidents that this was serious stuff, that the party leadership wanted and needed this.

David Cameron played a comparable role for Ruth Davidson at the Tory conference last week.

Secondly, there has, quite simply, been a retrenchment from the more ambitious version of last year. That has led Devo Plus - the organisation which advocates substantially enhanced devolution - to decry the Labour package as "tinkering".

In response to that, Labour's thinking is that their compromise version meets actual, popular desires as opposed to think tank ambitions.

It gives Holyrood added clout - while maintaining pensions and benefits on a UK basis. Potentially, it shoves up taxation and council tax for the wealthiest.

The benefits devolved are linked to current controversies: as in housing benefit and the "bedroom tax". It ticks Labour boxes. It is innately political - rather than merely administrative.

'Revitalised UK'

Thirdly, there is a broader narrative - which, to be fair, also featured in Calman and, to a degree, in the interim commission report.

That narrative is to entrench Holyrood against any depredation of its powers.

But, more, it is to entrench and stress the continuing role of the UK. As in Gordon Brown's preview speech, it is emphasised that it is the UK which will deliver defence, security and common welfare such as pensions.

By that narrative, a revitalised UK is on offer.

The thinking is that the Union of 1707 was voluntary, rather than an act of conquest. (Discuss: please write on one side of the paper only.)

The thinking is that the September referendum offers an opportunity to reassert that voluntary Union.

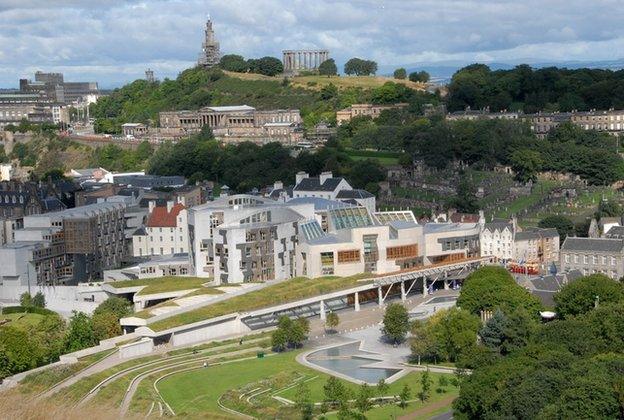

The debate has become about more Holyrood powers versus full independence

So, it is argued, those who vote "No" to independence will simultaneously be voting Yes to the reformed Union now on offer.

Except, say the Nationalists, it isn't really on offer. At least not in the way that independence is.

Vote "Yes" on September 18 and Scotland is on the road to independence. Vote "No" and conditionality kicks in. Which party will win the next UK general election? Can they be trusted to deliver enhanced devolution?

Asked by the wicked media whether Labour would include the new plan in its UK manifesto, Johann Lamont replied succinctly: "Yes."

Asked by the w.m. whether there would now be a pan-Unionist offer, Ms Lamont took a little more time to reply.

She was open to co-operation, if possible, but this was Labour's offer to be delivered by a Labour government.