Battle of Bannockburn: What was it all about?

- Published

The Battle of Bannockburn, fought on 24 June 1314, was one of the most famous events in the wars of independence.

It saw the Scottish king, Robert the Bruce, win a key victory over the English forces of King Edward II, despite being outnumbered two-to-one and facing what was regarded as the finest army in the medieval world.

On the 700th anniversary of the battle, here's some things you might not know about the historic event.

Where was it?

It was one of the most famous battles ever fought, yet nobody's sure exactly where it happened.

The backdrop was Stirling Castle, the last English stronghold in Scotland, which was targeted by Robert the Bruce while on the comeback trail during the wars of independence.

The constable of Stirling agreed to hand over the castle to the Scots unless an English force arrived to relieve him by the 24 June, 1314. They duly pitched up the day before.

Robert the Bruce was thought to have made his stand on what's now known as "monument hill", where his statue sits.

It was the perfect location, on high ground with a good field of vision, but getting up the hill to fight would have been a massive challenge for the English forces.

It seems more likely the main battle was fought on a nearby area of flat, low ground known as the Carse, where the English had camped overnight.

Medieval minefields

The main threat to Robert the Bruce's forces was the fearsome English cavalry - 2,000 heavily armoured men on horseback which could easily crush infantry.

Thinking outside the box, Bruce ordered hundreds of holes, measuring just a few feet, to be dug at a crucial point where the English army was advancing.

The small pits, capable of snapping horse's legs, meant the cavalry had to stick to a narrow Roman road and, unable to fan out, were left defensively vulnerable.

Killer hedgehogs

Robert the Bruce's other great anti-cavalry weapon was the "schiltron" - a body of troops wielding long pikes.

Looking like massive, deadly hedgehogs when fully formed, the tightly packed group would deploy their pikes on three levels, creating a wall of death which was virtually impregnable to a heavy horse charge.

This sort of tactic was vital, since many Scots couldn't even afford swords let alone war horses, and often had to make do with axes and other working tools.

First blood

The day before the main battle saw an event which set the tone for what was to come.

Sir Henry De Bohun, a young English knight looking to make a name for himself, arrived with a vanguard and spotted Robert the Bruce addressing some of his men.

The story went that Sir Henry, seeing an opportunity to take down the king of Scots, got tooled up and charged.

Bruce, armed with only an axe, reciprocated - taking out Sir Henry with such force that his head split in two, from the skull to the chest bone and breaking his weapon in the process.

Another much less heroic account, said to be from an English eyewitness, stated that Robert the Bruce clocked Sir Henry and cut him down as he was trying to get away.

Whatever the truth, English cavalry then charged the Scots, only to taste the sharp end of the schiltron. It was a morale dampener.

For Love

As King Edward arrived on the battlefield, did he also see the defeat of Robert the Bruce as an opportunity to settle a personal score?

Back when his father, Edward I, was on the throne, he hired an English nobleman called Piers Gaveston to work in his son's household.

Chroniclers at the time suggested Gaveston and the then Prince Edward became lovers, and the noble was sent into exile.

On his elevation to the throne Edward II recalled Gaveston, bestowing on him an earldom and other gifts.

But the other English nobles - enraged at the privileged access he had to the king - banded together to see Gaveston banished once again.

According to the contemporary book Vita Edwardi Secundi (The Life of Edward II) the king, sometime before Bannockburn, promised full recognition for Robert the Bruce as king of Scots, in return for giving Gaveston refuge in Scotland.

Bruce refused, and Gaveston was eventually executed in England as an enemy of the state.

Put simply, King Edward may have seen victory at Bannockburn as an opportunity to avenge Gaveston's death on Robert the Bruce, and force the English nobles to bow to his will.

Praying for victory

The main battle commenced not long after first light, on 24 June, 1314.

The Scots forces emerged from Balquhidderock Wood, before getting down on their knees to pray.

The tactic was more than spiritual - it allowed the captains an extra crucial few minutes to form up the battle lines.

Nevertheless, across the Carse, King Edward, with his 16,000-strong army, thought the Scots were surrendering.

He got a shock when prayers finished and the Scots got ready to attack.

Pride before a fall

As battle drew near, a row broke out between King Edward and the Earl of Gloucester, one of England's most powerful men, who complained the English forces needed rest after spending a sleepless night in marshland getting eaten alive by dreaded Scottish midges.

When the King accused the 23-year-old earl of cowardice in front of the men, Gloucester - pride fully dented - jumped on his horse and charged towards the Scots.

He was promptly met by - yes, you guessed it - the business end of the schiltron, and carved up in full view of both sides. Another morale dampener.

Watery grave

The Bannockburn - the long, snaking waterway after which the battle was named - proved to be Kind Edward's nemesis.

As battle commenced, the Scots troops moved across the battlefield, to close the gap.

Penned in between the burn - in reality a large river in some places - and the Scots pikes, the English forces had no choice but to cross back over the waterway, which was almost impossible because of the heavy armour they wore.

As the Scots pushed forward, the English became penned between the water and the enemy pikes, and panic gripped the ranks.

Even the archers, the other feared super-weapon of the English army, ultimately proved useless because the crush left them with no space to shoot arrows.

The getaway

Sensing defeat, King Edward's minders dragged him off the field and fled towards Stirling Castle.

But he wasn't well received by the remainder of the English garrison, who told him it was best if he didn't come in.

Shunned by his own men, the king ended up in the East Lothian coastal town of Dunbar, where he got a lift back to England on a ship.

What changed?

It's arguable whether the Battle of Bannockburn settled all that much.

Despite the outcome, Robert the Bruce had to wait another 14 years for the king's son, Edward III, to recognise him as the rightful king of an independent Scotland.

Bruce died just one year later, in 1329, while the wars of independence rumbled on.

However, if nothing else, Bannockburn did establish Robert the Bruce as someone who was not to be messed with.

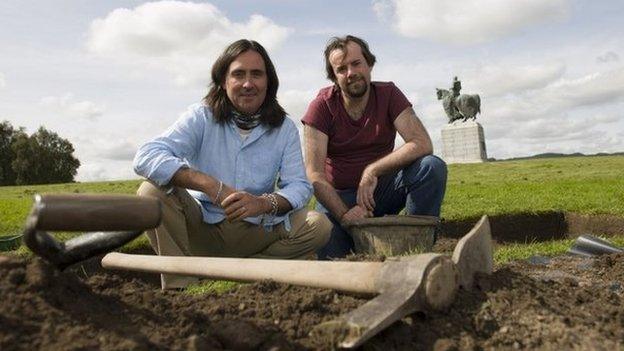

The Quest for Bannockburn, presented by Neil Oliver and Tony Pollard, is being shown on BBC Two at 20:00 on Sunday, 29 June.