Glasgow's man: David Grevemberg ready to deliver Commonwealth Games

- Published

David Grevemberg is, in his own words, "grinning from ear to ear".

I've just been telling him how excited my six-year-old son is about the Commonwealth Games.

With only a week to go until the opening ceremony, the man tasked with delivering this global event says the fact that children are getting involved and enthused is one of the main things that drives him.

"That's a wonderful thing to hear," he says. "Children have enormous value to contribute to an event like the Commonwealth Games. It's building the future right now."

Growing up

Grevemberg's own childhood was spent in New Orleans, Louisiana. He was quite literally the only white kid on the block.

"Growing up in that environment - you don't appreciate it until you get away from it and reflect on it," he says.

"I grew up in downtown New Orleans, or what Glaswegians would call 'city centre'. I went to public school there and really was the minority in my neighbourhood."

At the age of 12, he began commuting to private school in order to pursue his sporting ambitions.

"I spoke differently," he recalls, "I acted differently and I dressed differently. I was almost like the minority in both locations."

However, he says sport was "the equaliser".

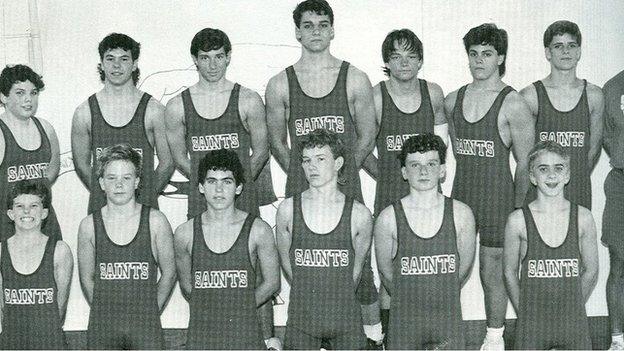

Grevemberg (centre, back) wrestled for school and college teams at national and international level

"Whether I was playing American football, wrestling or doing track and field, sport was really a way of being part of the team."

And it was in wrestling where Grevemberg was to shine.

He competed first in school competitions then at national and international level as he studied on a scholarship at Springfield College in Massachusetts.

Grevemberg says growing up in the deep south gave him a heightened sense of cause and drive.

"My grandfather used to tell me 'confidence will make you good son, but drive will make you great'," he says.

The highlight of his wrestling career was coming second in the US International Open.

'High expectations'

He dreamed of competing at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992 but failed to qualify and then injury cruelly quashed his hopes of representing Team USA on home soil at Atlanta in 1996.

"The injury was a defining moment," he says. "It brought me down to earth and I had to make a choice - and the choice was to focus on my career."

He made the transition from athlete to sports administrator and, more importantly, he made a career-defining move into the Paralympic movement, working with the US team going to Atlanta.

"At that time, the movement had a real identity crisis," he says.

Grevemberg worked to change the face of the parasport movement before coming to Glasgow

And Grevemberg is widely credited with helping change things. "It was about legitimising it," he says.

"You can't be credible until you are legitimate and that required a lot of tough love, honest conversation and courageous moments."

He cites "setting standards" and having "high expectations" as the means by which he went about making Para-sport more credible.

"We put qualification criteria down for the first time," he explains. "Regardless of the nature of disability or classification, if you're not going to win a medal, you don't go."

The team took the top spot in the medals table and Grevemberg's career also took off.

"I attended my first International Paralympic Committee (IPC) General Assembly in Tokyo," he says.

"I was the youngest person there by about 10 years, but I saw it as a great opportunity to really impact on and change the governance of the sport."

Grevemberg went on to spend 11 years in Germany as executive director of sport with the IPC.

He then took his mission to transform Para-sport to the Commonwealth Games - a path that eventually led him to Glasgow.

"It was perfect timing," he suggests. "After all those years of travelling, I was looking for another opportunity.

"Glasgow reminds me so much of New Orleans. It was almost a 'coming home' in some ways."

And, by the time he moved to Scotland to take on his role at Glasgow 2014, he was not alone - he brought his wife and two children, then aged six and four.

"We were immediately welcomed into this magical city and now really feel part of the community," he says.

The family made their home in the picturesque village of Gartocharn on Loch Lomond and are, in fact, so much a part of that community that they'll remain long after the athletes leave.

Grevemberg has already secured a new role - working as the chief executive of the Commonwealth Games Federation in London. But he will commute and his family will stay where they are.

"I call the children my 'wee Scots'," he says.

Grevemberg has put much focus on engaging young people with the Games

Grevemberg's Games role has led him to rub shoulders with some very high-profile people

So for the Grevemberg family the legacy of the Games will be a future in Scotland, but its the legacy for Glasgow, and Scotland as a whole, that Grevemberg has always been so keen to promote.

He talks of the infrastructure created; the new venues that are "world-class but also community led"; the boost to tourism in the city; the Queen's Baton Relay, which has celebrated "extraordinary, ordinary people", and the work that has gone on to increase accessibility and encourage future sporting events to Glasgow.

Grevemberg hopes the reputation of the city has been enhanced and that other host cities will look here to learn lessons.

"With things like the temporary track at Hampden, we did something innovative in keeping with the engineering culture of Scotland," he says.

"The world of athletics is now calling it the 'Glasgow solution'."

'Bold and audacious'

But it's the social legacy of the Games that Grevemberg is most animated about.

He talks a lot of "conversation" and says many of the things Glasgow 2014 has done has helped prompt debate.

He cites the hugely controversial decision to bring the down the Red Road flats as part of the opening ceremony - and the subsequent u-turn after the widespread criticism - as a "bold and audacious, but obviously painful" move.

"Our decision to change on that emphasises the importance of conversation and courageous action," he says.

"People talked about it. It was controversial, but people were expressing their opinions."

And it's those awkward conversations Grevemberg hopes the Games will stimulate, not just in Glasgow but across the Commonwealth.

"We are the first organising committee to put out a human rights statement.," he points out. "Our cultural programme is looking at issues like slavery and homophobia. These can be uncomfortable but are so important."

The controversy over the Red Road flats got people talking and started an "important conversation"

Grevemberg says the opening ceremony at Celtic Park will "set the tempo" for the Games

Early in the interview, Grevemberg promises to give me his "spiel" about the values of the Commonwealth and he delivers.

But, as he talks about humanity, equality and destiny, it is clear this is not just a run-of-the-mill sales pitch. He truly believes in what he's promoting.

I ask what success will look like and he talks about the opening ceremony "setting the tempo" and the city "coming alive" as people get "caught up in the action and stirred up in the passion".

"It's going to be about Glasgow saying: 'We did this - these are our Games.' I really want Glasgow, and Scotland, to teach the rest of the world how to do it right," he says.

He turns once again to the importance of young people.

"It's about the kids out there seeing for the first time this sporting spectacle in their backyard."

And for a judgement on his personal success, the Games chief will also look to the kids of the Commonwealth - his own two children.

"They are so excited about the Games," he says. "They are two of my biggest critics but also evangelists at the same time.

"I'll come home and say 'What do think of this?' and they'll say 'Oh Dad, that's rubbish' or 'We love that, it's great Dad'.

"I'll use them as my real barometer on things."