Political parties make power play

- Published

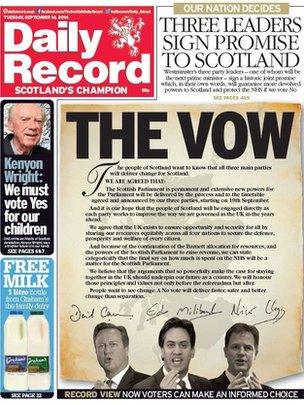

The pledge was carried on the front page of Tuesday's Daily Record newspaper

Perhaps it might help if we took a little look at the pledge of more powers set out by the pro Union parties today.

The one that was trailed last night by Gordon Brown and covered on the telly and the wireless.

Firstly, it would appear to confirm the prime minister's acknowledgement that any notion of deferring the issue of more powers - conceptually if not yet in agreed detail - has been abandoned.

No more talk of settling the question of independence then turning to more powers. The pro-Union parties have seemingly concluded that they must be more upfront, now, about their plans.

That is a conclusion driven by strategy. Let us now look at the detail of the promises one by one. To help this consideration, here they are:

The Scottish Parliament is permanent and extensive new powers for the parliament will be delivered by the process and to the timetable agreed and announced by our three parties, starting on 19th September.

And it is our hope that the people of Scotland will be engaged directly as each party works to improve the way we are governed in the UK in the years ahead.

We agree the UK exists to ensure opportunity and security for all by sharing our resources equitably across all four nations to secure the defence, prosperity and welfare of every citizen.

And because of the continuation of the Barnett allocation for resources and the powers of the Scottish Parliament to raise revenue we can state categorically that the final say on how much is spent on the NHS will be a matter for the Scottish Parliament.

For those of us with long memories, number one - re permanence - is a bit of a throw back.

The cross-party Constitutional Convention, which paved the way to the current Holyrood Parliament, wrestled long and hard with the issue of "entrenching" the Scottish Parliament.

After endless argument, they concluded that, constitutionally, entrenchment was impossible.

Holyrood is a creature of Westminster statute. No Westminster parliament can bind its successors. Strictly, therefore, no Westminster parliament can prevent a future Parliament from rescinding devolution.

The convention concluded that the way round this was for there to be a solemn and binding declaration by the Westminster Parliament that they would do no such thing. In the event, devolution was overwhelmingly endorsed by the Scottish people - and the solemn declaration was quietly forgotten.

Westminster sovereignty

Which, say supporters of the new plan, tells you a lot. It tells you that the concept of unalloyed Westminster sovereignty is, in effect, consigned to history, as Gordon Brown has repeatedly argued.

It tells you, goes the argument, that the Scottish people are sovereign with regard to their own destiny - as are people in the other constituent parts of these islands. Whatever Westminster tradition says.

Thus, it is argued, the devolved Scottish Parliament is permanent as a consequence of the 1997 vote - and this would be entrenched by a "No" vote in Thursday's plebiscite.

By popular choice, in short, not constitutional history. The three pro-Union parties would, individually and collectively, endorse this notion.

Look next at promises two and three. Equity in resources and the retention of Barnett allied to enhanced tax powers for Holyrood. Might these not be mutually contradictory?

Conservative leader David Cameron, Labour leader Ed Miliband and Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg have signed a pledge to devolve more powers in the event of a No vote in the referendum

Consider this.

Historically, every incoming Secretary of State for Scotland was greeted with a gentle little suggestion from the Treasury that there should be an overall assessment of relative budgetary need across the UK.

And who might conduct this review? Why, the Treasury of course. They had the expertise. The likely consequence for Scotland? A reduction in budgets unless a very good case could be deployed.

Consider further.

Clause two of the pledge seeks equity across the four nations of the UK. Wales is one of those nations and Wales cordially loathes the Barnett Formula, seeing it as a malevolent device to deprive their people of funding.

Indeed, there was an expert commission on the subject which concluded, inter alia, that substantial sums might usefully be withheld from Scotland as part of a reassessment of funding.

Might this not clash with Clause three of the pledge? Especially if pursued by a future Westminster government with more interest in "equity" than Scotland's "needs"?

Recalibrating Barnett

No, say supporters of the plan. Read Clause three. That trumps Clause two - and is inserted deliberately to do so. Barnett stays.

Further, they say, the first minister of Wales is careful to say that he wants to enhance Welsh spending - without in any way robbing Scotland.

Any mutual contradiction is illusory and over-ruled in practice. Supporters of independence say: give Scotland autonomy then let the rest of the UK assess relative need.

Which brings us to Barnett. If Scotland gets enhanced tax powers, then Barnett would change.

The proportion of the Scottish budget to be raised by block grant would shrink as the tax powers kicked in.

Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond says only independence will give Scotland the extra powers it needs

That means recalibrating Barnett which determines the annual changes in the block grant by comparison with relevant English spending departments.

It does not mean, say supporters of the Union, that Scotland's budget would be cut. Just that more would be raised in direct taxation in Scotland.

And what say supporters of independence? They say the plan is rushed and implausible. They say that it cannot be guaranteed, given, among other things, grumblings of discontent from Tory backbenchers.

They say further that, even if it is implemented, it would oblige Scotland to rely over much on income tax to protect, for example, the NHS from further depredations.

By contrast, independence would give Scotland full control over the entire basket of taxes and duties.

To which supporters of the Union reply that it is sensible to maintain certain revenue sources such as National Insurance at the UK level to cover shared benefits and demands.

They say that the Scotland Act 2012 gives Scotland taxation powers beyond income tax alone.

Your referendum, your choice.