What now for 'the vow'?

- Published

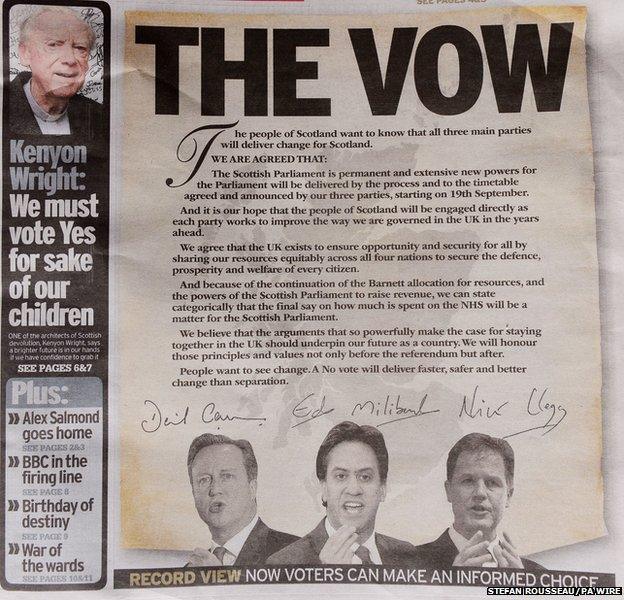

David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband all pledged support for more powers for Scotland

In the aftermath of a bruising, exhausting and above all lengthy campaign, much has been made of "the vow".

On Tuesday 16 September, two days before the referendum, the three UK party leaders joined forces on the front of a Scottish tabloid newspaper.

With the polls suggesting the race was neck and neck, David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg personally pledged that a "No" vote would deliver "faster, safer and better change" than would independence.

"Extensive new powers for the parliament will be delivered by the process and to the timetable agreed and announced by our three parties," they wrote.

The parchment-style front page seemed to suggest ink rather than blood but the idea was the same.

"This is solemn," it said. "You can trust us."

So what of "the vow" now?

It was certainly carefully worded. The pro-UK parties had indeed agreed, at the eleventh hour, on "a process" and "a timetable" to deliver extra powers.

But they had not agreed, and still do not agree, on the powers themselves.

The UK party leaders' promise appeared on the front page of the Daily Record ahead of the referendum vote

The man charged with turning the heat of disagreement into the light of a deal is Lord Smith of Kelvin.

Some job.

The Smith Commission will bring together the Scottish Labour Party, the Scottish Liberal Democrats, and the Scottish Conservatives from one side of the Yes/No divide, with the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Scottish Green Party on the other.

'Radical redesign'

Senior SNP figures say they will use the process to argue for a radical redesign of the UK, in which a powerful federal Scotland has complete control over tax and spending with only defence and foreign affairs reserved to Westminster.

The SNP, in the form of its leader-in-waiting Nicola Sturgeon, is already arguing that the language deployed in and around "the vow" was "something close to federalism or home rule, external."

"This took it beyond the detail of what the parties had previously offered," she was quoted as saying, adding: "People are not going to be easily bought off by a few more powers."

The 45% who voted for independence along with a substantial proportion of the 55% who didn't because they were convinced by "the vow", add up to make a powerful majority for big change, reasons the SNP.

Labour, which appeared happy enough at the time of the Daily Record article to give the impression that something new was on offer, is now busy briefing that "the vow" did nothing more than re-state the party's commitment to implement the proposals contained in its Devolution Commission, external report published in March 2014.

Lord Smith of Kelvin has been appointed to chair a commission on further devolution

Of the three UK party commissions published before the vote, Labour's was the longest - at 298 pages - but also the most cautious, rejecting a "strong case" in an interim version of the report for the complete devolution of personal income tax.

Instead it recommended a complicated arrangement which would have the effect of allowing the Scottish Parliament to increase but not cut the top rate of tax.

The report also said the "core of the welfare state" should remain under Westminster control, as should various taxes including air passenger duty.

Attendance allowance and housing benefit should be devolved, allowing MSPs to abolish the spare room subsidy or "bedroom tax", and Holyrood should also have control of the Scotrail franchise, administration of the work programme, which provides support and training, and the operation of the Crown Estate, which looks after seabed development.

'Home rule'

Labour's problem is that the other four parties in the room with Lord Smith all want to go further, in some cases much further.

The Liberal Democrats hope to fulfil their old dream of "home rule all round" or in other words, a federal UK.

This would involve the devolution of significant powers both to Holyrood and to local councils with the exception of foreign affairs, defence, the currency, immigration, trade and competition, pensions and welfare and macro-economic policy, all of which would be controlled by the federal government.

The UK single market for business would be preserved but income tax paid by Scottish taxpayers would be "almost entirely the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament," with the exception that allowances, reliefs and the threshold at which income starts to be taxed would remain the same across the UK.

Scottish rates of capital gains tax, inheritance tax and air passenger duty should be set in Edinburgh, say the Lib Dems.

Corporation tax should not be devolved although its proceeds raised in Scotland should be allocated to the Scottish Parliament's budget.

Responsibility for national insurance, pensions and most benefits should rest at federal level.

SNP leadership candidate Nicola Sturgeon said "something close to federalism or home rule" was offered

The report of the Home Rule and Community Rule Commission, external, chaired by a former party leader Sir Menzies Campbell, and published in October 2012, skipped lightly over the high hurdle of how to build a federation when the vast majority of taxes are raised in one of its four constituent parts.

Sir Menzies' report suggested that Scotland could lead the way, embracing home rule first, with full federalism following when the position of England was sorted out.

It gives a new twist to an old Lib Dem joke.

What do we want?

Constitutional reform in the shape of home rule leading to a federal UK!

When do we want it?

In due course!

Even the Conservatives, for so long staunch opponents of devolution, have gone further than Labour, proposing that Holyrood takes overall control of personal income tax including the ability to set rates and bands.

Lord Strathclyde's Commission on the Future Governance of Scotland, external rejected the transfer to Holyrood of national insurance, corporation tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, pensions and most benefits.

But it recommended housing benefit and attendance allowance be devolved, along with air passenger duty and "smaller taxes and duties" if Scottish ministers should want them.

Lord Strathclyde said he would have gone further, recommending the devolution of VAT were it not prohibited by EU law which prevents sales tax variation within member states.

Instead he suggests a share of VAT receipts raised in Scotland should be allocated to the Scottish Parliament.

United before the referendum: Tory Ruth Davidson, Labour's Johann Lamont and the Lib Dems' Willie Rennie

Pickled Ed

All of which leaves the Labour leader Ed Miliband in a pickle.

If his party resists moves towards more radical constitutional change and is blamed for any perceived failure of the Smith Commission, the SNP and others will seek to punish the party electorally, both in the general election of 2015 and the Holyrood election the following year.

A "Yes" vote in its heartlands, including Glasgow, has already shaken Scottish Labour, with talk of a challenge to Johann Lamont's leadership and worries about rocketing membership figures for the SNP, Scottish Socialist Party and the Greens.

The worry for Labour is that it is has been tarnished in the minds of Scots sympathetic to the independence cause, whether "Yes" or "No" voters, because of its apparent alliance with big business, big banks, big media and, above all, the "big, bad Tories".

Ms Lamont insists this is nonsense, saying the two parties disagree on most things but "I did agree that Scotland should stay in the UK", external.

On the other hand, if Labour signs up to the devolution of significant extra powers to Scotland, the demands from England for a solution to the West Lothian Question - Scottish MPs voting on English issues like health and education, when English MPs can't vote on such devolved Scottish issues - will become harder to ignore.

For a party with such solid support in Scotland for so long, excluding the big block of Labour MPs from north of the border from key commons votes on domestic English legislation could be problematic.

While the subject is more complicated than it first appears, external, it is a challenge for Mr Miliband to present his rejection of David Cameron's siren call for English votes on English issues as principled rather than self-interested.

Labour insist they can deliver meaningful change for Scotland within the existing framework.

Either way, the issue is a thorny one for Mr Miliband and - one way or the other - may make it harder for him to gain or retain the keys to Downing Street.

The referendum is already history.

But this is not over yet. Not by a long way.