Johann Lamont resignation: Two versions of the story

- Published

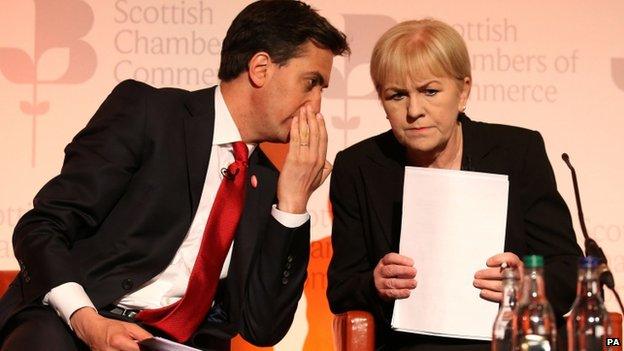

Ed Miliband, UK Labour leader, and Johann Lamont, Scottish Labour leader appear together during the referendum campaign

There are two leading parties in Scotland. One, the SNP, was on the losing side in the independence referendum. It has quadrupled its membership - and is defiantly buoyant.

The other, Labour, was on the winning side in the referendum. It is in despair and disarray. It takes a certain malign genius to achieve that. A gold standard in foot-shooting.

There are two versions of this story. In one version, Scottish Labour's departing leader, Johann Lamont, accuses her Westminster colleagues - and, by implication, Ed Miliband - of undermining her and failing to grasp how much Scotland has changed. She says some of her MP colleagues are "dinosaurs".

Final straw

By this version, she was thwarted in her ambitions to increase the party's offer of more powers to the Scottish Parliament. And, certainly, it is true that the original draft of the party commission she established was "minded" to support the full devolution of income tax to Holyrood. Minded, that is, until sundry MPs intervened.

By this version, she was never given scope to be, authentically, the leader of the entire party in Scotland. And, certainly, it is true that she was seldom viewed as such by MPs, particularly those of more established vintage.

The final straw for Ms Lamont was, apparently, the move to oust Labour's general secretary in Scotland - without consulting her in any serious fashion. It was this which led to her claim that Scottish Labour was still treated as a "branch office."

Even Ms Lamont's Westminster critics - and there are one or two - concede privately that this episode was crass in the extreme, given the sensitivity surrounding the handling of internal party issues in Scotland following the Falkirk selection row.

Ms Lamont said she was not consulted on the move to oust Labour's general secretary in Scotland

The alternative version is that Johann Lamont wasn't up to the job - that she failed to counter the SNP, that she failed to modernise the party sufficiently to cope with a new Scotland where people are no longer prepared to back Labour as a duty, that she failed to attract new talent who might freshen up the party's portrait for the electorate in 2016, when Holyrood goes to the polls.

And, certainly, she has displayed little sign of a persistent appetite for confronting the Nationalists on the constitution. Her friends, though, would say this is because her instincts lie with a different form of politics: with tackling poverty and asserting gender equality.

Even if that latter point is true, though, the game in town for now remains the constitutional battle. Ms Lamont might have preferred to be pursuing other avenues. Snag is her party did not win the 2011 Holyrood election. Indeed, Labour was comprehensively defeated. The Nationalists were perfectly entitled - indeed, mandated - to pursue the referendum.

Murmuring of discontent

It also remains entirely legitimate for there to be close scrutiny of the possible new powers for Holyrood, not least because that promise (delivered by a former Labour PM) formed a key part of the final pitch from the pro-Union side.

Ms Lamont's attitude appeared to be: will it never end? It will end when the energised electorate of Scotland is satisfied, or at least approximately so. Not a moment earlier

She could, I guess, have dealt with the occasional murmuring of discontent from Westminster backbenchers. Ed Miliband faces it constantly. For David Cameron, it is a daily joy. And Nick Clegg….

However, she felt - with the general secretary episode - that Labour had demonstrably failed to grasp the true nature of modern Scottish politics, failed to realise the need to be truly Scottish, to put Scottish interests first, to align comprehensively with the wishes of the Scottish people.

There may be a degree of truth in both of these narratives. Folk can judge for themselves. However, either version is a gift to the SNP. Nicola Sturgeon says her chief rivals are in "meltdown". Rebuttal? No, thought not.

Ms Lamont campaigned for a No vote in the Scottish independence referendum

So where next? Johann Lamont says she remains part of the Labour family - while hoping that it will be "led by someone who knows how to treat family members properly". Ouch and again ouch.

As for Scottish Labour, it must now choose a new leader. (It has had a fair bit of practice in that regard in recent years.)

Might it be an MSP? Possibly, perhaps one of the younger aspirants such as Kezia Dugdale or Jenny Marra. Talented, both.

It could be argued that Ruth Davidson has done pretty well as a young, relatively inexperienced leader of the Conservatives. As, indeed, she has, to general acclaim.

But today's Tories can sometimes seem touchingly grateful that anyone will lead them at all. Plus they only have one MP - who is disarmingly loyal.

Grade A guddle

Leading Scottish Labour is rather a different challenge - and may be felt to be over-much for an MSP with a shortish pedigree.

So an MP? Jim Murphy seems the top tip - although there is also talk of Anas Sarwar (the deputy who now acts up). Or even the big clunking fist of Gordon Brown. Can he move from saving the Union to saving Scottish Labour?

I would look towards Mr Murphy in the first place - although other options may be placed before the electoral college which will, once again, determine Scottish Labour's choice.

But can an MP head Scottish Labour when, according to Ms Lamont and common sense, the focus of Scottish politics has shifted so firmly towards Holyrood?

The answer is yes - with an important caveat. An MP can be elected - provided that individual then seeks to be Labour's candidate for First Minister at the Holyrood elections in 2016.

This is capable of resolution. Labour may emerge, refreshed, ready to make swift concessions on new powers in the Smith Commission and to try to get the Westminster agenda back to a choice of Miliband or Cameron as PM. Labour may find a new purpose in post referendum, post industrial Scotland.

It might. For now, this is a Grade A guddle.