HMP Grampian: Transforming Scotland's hate factory

- Published

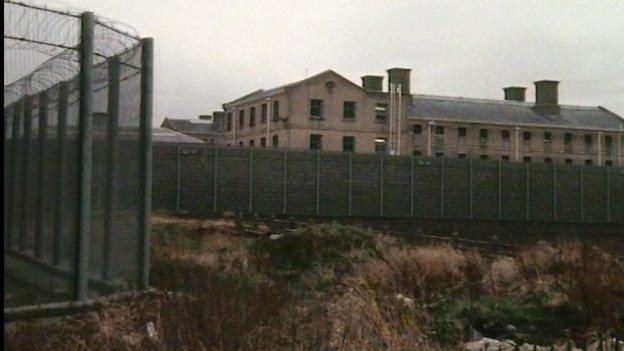

Peterhead had a fearsome reputation

In the mid-1980s prison officers at HMP Peterhead had to wear body armour at all times after a series of riots and hostage-takings. The new HMP Grampian, situated next to the old jail, wants to bring a very different approach to incarceration.

Victorian prison conditions, rooftop protests, riots and hostage-taking gave HMP Peterhead a mythical status. It became known as Scotland's hardest lock-up, dubbed by many as the "hate factory".

The history of the prison, on the Buchan coast, 30 miles north of Aberdeen, dates back to 1888.

The jail was built to provide workers for the quarries which would be supplying granite blocks to construct the breakwater to protect the fishing fleet in the town's harbour.

The sea walls were built using stone produced from the hard labour of the tough men who first inhabited Peterhead prison.

Peterhead was built in 1888

In those days, prison was designed for punishment and was stocked with its own supply of whipping implements such as cat-o'-nine-tails and birch rods. The prison officers carried cutlasses.

In the early years of the 20th Century Peterhead welcomed its first political prisoner - Red Clydesider John Maclean - who was jailed for sedition during World War One.

He died at the age of 44, and blamed his deteriorating ill health on the conditions he had suffered in the north east jail.

If the conditions were considered poor in the early 1900s, its reputation did not improve as the years wore on.

The cramped Victorian building was enveloped by the chill winds from the North Sea and inmates spent most of their time in tiny cells with little recreation or rehabilitation.

Former inmate Johnny Steele shows how small the cells were in Peterhead

And difficulties with adapting the building meant it was not possible to upgrade the cells to provide internal sanitation.

Prison historian Robert Jeffrey tells a BBC Scotland documentary on the prison the fact that "slopping out" lasted so long was "disgraceful".

Mr Jeffrey says: "Taking prisoners in groups of around of 20, who have spent the night sitting on tin cans in their cells, downstairs to sluice all that out. It is out of the dark ages."

Slopping out ended across the prison service in 2007, except for Peterhead where they used chemical toilets.

Riots in the 1980s caused hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of damage

It was just one part of the system that inmates claimed pushed them over the edge.

Visiting was another sore point.

Prisoners, who were mainly from the central belt, said the distance made it difficult for their families to get there.

Peterhead was a powder keg and in November 1986 it finally blew.

Fifteen prison officers were assaulted when the trouble started and one of them, John Crossan, was taken hostage for four days.

From the roof, prisoners demanded to speak to Daily Record reporter Ian Cameron.

He recalls: "The young prison officer who they had taken hostage, they were threatening to throw him off the roof. I couldn't have lived with that so I had to go."

'Eyes like gobstoppers'

Mr Cameron interviewed riot leader Andrew Walker, a former soldier who had gunned down three of his colleagues in a botched payroll robbery.

"He started talking about his wife and kids and the difficulties of coming up from the Borders," he says.

"He wanted transferred to the south. I was looking at his eyes, when he was angry they were like gobstoppers."

After their chat, the Daily Record reporter asked Walker to hand over the prison guard and, to his surprise, he did.

More than £250,000 of damage was caused when prisoners set fire to A-hall during the riot.

The main culprits received an extra 10 years on their sentences.

It was no deterrent to further trouble.

Less than a year later, Peterhead hit the headlines once again.

This time the response from the authorities was devastating.

About 50 convicts went on the rampage and two officers in D-hall were taken hostage.

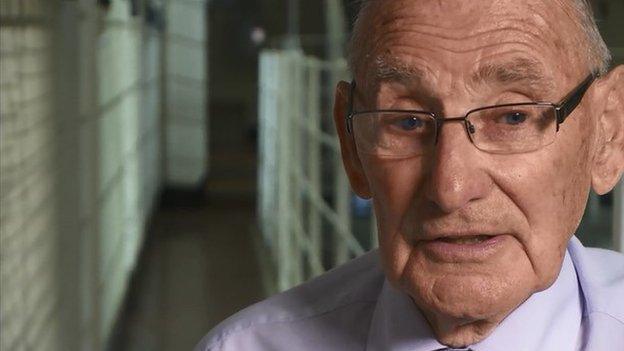

Former prison guard Jackie Stuart was held hostage during a riot

One of them, Jackie Stuart, who is now 83, told BBC Scotland: "They brought us out and made us lie on the floor with out heads under the bed. They started beating us with table legs.

"That carried on for a while then somebody shouted that was enough. We were pretty badly injured."

The hostage-takers let Bill Florence go because of his injuries but Jackie Stuart was paraded on the roof in front of the media.

There was a genuine fear his life was in danger.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher took the controversial decision to send in the SAS.

At 05:00 they blew their way in with CS gas, stun guns and grenades and rescued officer Stuart.

Former inmate Willie Leitch recalls that the entire operation was completed in just two minutes.

Historian Robert Jeffrey says: "They were back in their 4x4s and back to Herefordshire. One of them said he had enjoyed a second breakfast when he got back.

"It was really a very clinical, frightening strike."

Something had to change at Peterhead. A different approach to prison management was needed and a new governor, Andrew Coyle, was brought in from Greenock Prison in 1988.

Mr Coyle says: "Shortly before I went there the Secretary of State sent for me and said 'governor, I have got only one instruction for you'

"'Get Peterhead off the front pages'."

Andrew Coyle was governor of Peterhead from 1988

The SPS located all those who had been involved in riots and hostage-taking at Peterhead in an attempt to stabilise the entire prison estate.

The 60 inmates involved were initially held in "lockdown" under prison rule 36 which meant the governor had to visit each one every day.

Mr Coyle says: "The prisoners were all locked up in isolation. Many of them refused to wear clothing.

"They were clothed only in blankets, they themselves and their cells were covered in excrement. It was a terrible situation for staff and for them."

The daily clothing of the prison officers was riot gear - helmets, body armour and shields.

Mr Coyle says: "Staff would say: 'When I get up in the morning I have got a sickness in the pit of my stomach because I know I have got to put on all this body armour and go down to that terrible hall'."

The situation could not continue.

Sex offenders

Since most of the high security inmates were from the central belt, the SPS moved them to Shotts in Lanarkshire.

But what to do with Peterhead?

"There was no moment when the strategic decision was made to move all sex offenders to Peterhead," says former governor Coyle.

"It happened incrementally. The staff at Peterhead gained an expertise in managing sex offenders."

The former governor says that this was the only reason Peterhead was kept open.

The prison became a centre of excellence in the treatment of sex offenders through its pioneering STOP programme.

And by 2002, when the SPS wanted to close Peterhead, the people of the town marched against the closure and won.

However, the sex offenders were removed from Peterhead in 2011 and last year the prison finally closed its doors.

The new HMP Grampian hopes to transform prison life

The new HMP Grampian, which opened in March 2014, is a state-of-the-art prison which is designed to be "community-facing", taking inmates from the north east of Scotland and focusing more on rehabilitation and giving them skills.

It is the first time in Scotland that men, women and young offenders have been housed in the same jail.

The prison cells are much larger than those in Peterhead and, as well as including a toilet, they also have an en suite shower.

There is a sports hall, classrooms and workshops for the inmates to use but the problems of the old jail seem to be haunting the new HMP Grampian.

In its first eight months there have been a series of incidents. In the most serious, about 40 prisoners went on the rampage and, in an echo of 1980, officers wore riot gear to quell the trouble.

Are these teething problems? Does the community-facing approach just need time to work?

Former Peterhead inmate Johnny Steele says: "At the end of the day a jail is still a jail regardless of what is available to the prisoners inside, whether that be TVs, swimming pools or whatever. It is still a prison.

"What society needs to know is that the more help that people get in the prison the better it will be for when they eventually get released again."