Has free tuition made a difference to poorer students?

- Published

.jpg)

Has free tuition helped more youngsters from deprived backgrounds go to university? Or is it a "middle class benefit"?

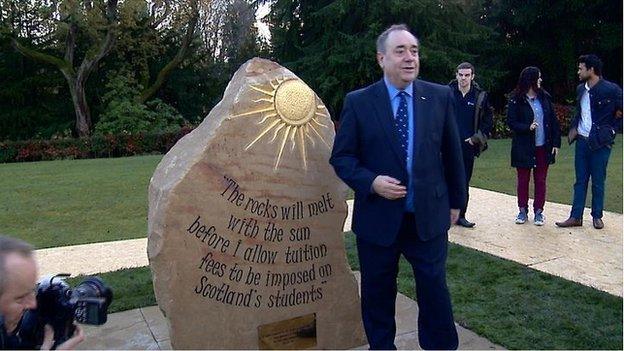

There was no denying Alex Salmond's pride in what he hopes will go down as one of his lasting achievements as first minister.

His memorable pledge that the "rocks will melt with the sun" before tuition fees are imposed on Scottish students has been made permanent in a plaque at Heriot-Watt University.

The abolition of tuition fees in Scotland was in stark contrast to moves south of the border. Students from England and Northern Ireland can now build up debts of £27,000 in three years from fees alone.

While some would argue that free university tuition is a matter of principle, the jury is out on whether the policy has actually helped more youngsters from less well-off backgrounds go to university.

Former education secretary Fiona Hyslop spoke of their removal as the removal of a barrier.

Labour, however, has argued that in recent years fewer students from disadvantaged backgrounds have actually made it into higher education.

It is important to remember, of course, that students and their families never paid fees upfront out of their own pockets.

Instead, the fees were repaid gradually once the graduates were earning a reasonable salary.

So what do the figures tell us?

An analysis from the Scottish Funding Council and the Higher Education Statistics Agency shows that the overall number of Scots starting university courses north of the border is close to a historical high but has fallen back in recent years.

From 29,145 in 2008 their ranks fell to a low of 26,620 in 2011. The number then started rising again and in 2012 it was back above 27,000.

But these figures are still high by historical standards. For instance, in 2005, 25,700 Scots started courses here while until the early 1990s, the number of young people with the opportunity to go to university was dramatically smaller - simply because there were fewer universities.

Institutions like Edinburgh Napier, Robert Gordon and what is now the University of the West of Scotland were colleges or polytechnics.

Alex Salmond unveiled a monument stone bearing one of his famous quotes

While the total number of new students has fallen back over the past few years, the proportion of them from a deprived area has gradually risen.

In 2012, 13.3% of new university students were from the most deprived areas compared to 12.3% the year before.

The figure for 2013 is expected to show a significant rise as new agreements came into force between the Scottish Funding Council and universities, which committed universities formally to widening access for the first time.

So, at the very least, there has been no overwhelming change in recent years.

But away from the soundbites, few supporters ever claimed that the abolition of fees would in itself widen access.

Rather the argument was put on its head: what young person from a deprived background could possibly be attracted to university by the prospect of hefty fees?

More importantly, it is widely accepted giving more young people the chance to get to university is about far more than encouraging students in S5 and S6 who already have the right qualifications.

It means, to use the jargon, early intervention, which extends right the way through school starting off in primaries.

Apart from straightforward educational benefits, schemes like this can help "normalise" the idea of going to university for youngsters or parents who might not have considered it. Barriers can sometimes be perceived rather than real.

Since 1945, every government north and south of the border would claim to have been committed to the idea of helping the brightest youngsters succeed academically regardless of their personal background even if there has often been intense debate about whether their policies were actually helping or hindering.

If there was a straightforward way of helping more from disadvantaged areas to get to university, it would have been done by now.

Instead the answer involves a complex mix of questions over funding, school performance and persuading youngsters university is for them.

- Published18 November 2014

- Published3 September 2014

- Published11 July 2013