Nan Shepherd: How one woman saw the Cairngorms in a different light

- Published

The Cairngorms are among the wildest landscapes in the British Isles but a long-forgotten literary masterpiece challenges the ways in which mountains should be viewed.

Hundreds of books have been written about mountains, mostly by men.

The goal of reaching the summit and the language of conquest and victory have been ever-present in works about mountain regions.

Award-winning nature writer Robert Macfarlane says his vision of the Cairngorms was radically altered when he read Nan Shepherd's poetic and philosophical journey "into" the mountains.

Her book, The Living Mountain, was written during World War 2 but was not published until 1977.

In more recent years she has found a new generation of readers, helped by its inclusion in Canongate's "Canons" series.

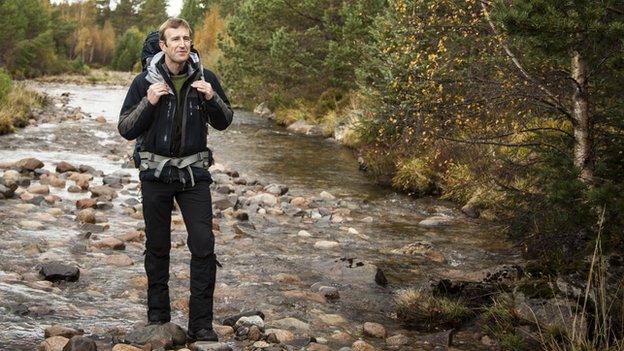

Macfarlane, who presents the BBC documentary The Living Mountain: A Cairngorms Journey, discovered the book about a decade ago.

He says it changed the way he looked at mountains.

Nan Shepherd lived in the same house in Aberdeenshire for 87 years

"It was quiet, wise, humble and sensuous," he says.

"It was a meditation not a manifesto. It was a pilgrimage and not an attack."

Macfarlane says Nan Shepherd was in love with what she called the "tang" of height.

She wrote: "Summer on the high plateau can be as delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge.

"To those who love the place, both are good, since both are part of its essential nature. And it is to know its essential nature that I am seeking here."

Robert Macfarlane travels in the footsteps of Nan Shepherd

According to Macfarlane, two beautiful ideas emerge from Nan Shepherd's book.

The first is that we should not walk "up" a mountain but "into" them, thus exploring ourselves as well as them.

She wrote: "Beginners want the startling view, the horrid pinnacle, sips of beer and tea, instead of milk."

Like her fellow Scot, the environmentalist John Muir, she believed "going out" was actually "going in".

Secondly, Macfarlane says Shepherd "abandons the summit as the organising principle of a mountain".

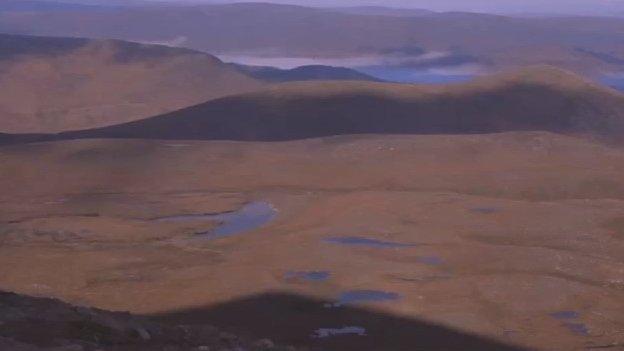

The battleship flanks of Carn a' Mhaim

The meanderings of the Dee as seen from the high plateau

As Nan goes "stravaigin" about the mountain she explores it in minute detail, describing herself as "a peerer into nooks and crannies".

Shepherd wrote: "Often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend, with no intention but to be with him."

Nan Shepherd was born in the village of Cults on the outskirts of Aberdeen in 1893. She lived in the same house for 87 years.

In 1915, she graduated from Aberdeen University and spent the next four decades in the rather conventional confines of Aberdeen College of Education, where she taught teachers how to teach.

Between 1920 and 1933, she published three novels set in small rural communities in north east Scotland.

As she got older she began to exercise her restless limbs in the foothills of the eastern Cairngorms, about 50 miles from her home.

She was fascinated by what happened to mind and matter at height.

As she wrote to a friend in 1940: "To apprehend things - walking on a hill, seeing the light change, the mist, the dark, being aware, using the whole of one's body to instruct the spirit ... it dissolves one's being. I am no longer myself but part of a life beyond myself."

By the summer of 1945 she had completed a book on what she called the "total mountain".

She sent the manuscript to her friend and fellow novelist Neil Gunn.

Although he admired the work, he was sceptical about the possibility of it getting published and so it sat gathering dust for 32 years.

It was finally published in 1977, four years before Shepherd's death, and has been growing in influence since.

Each chapter of the book mixes field notes, lyrical memoir, oral history, natural history and an almost zen-like meditation of the nature of landscape and consciousness.

Macfarlane says her subtle style is both witty and lyrical.

"It is at ease with the theological as well as the geological," he says.

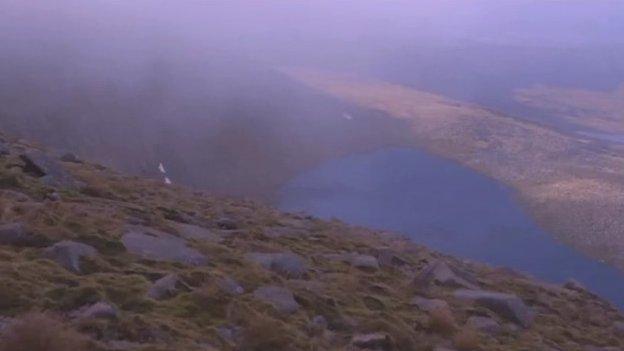

Loch Coire an Lochain seen from the ridge above

Loch Coire an Lochain - one of the secrets of the Cairngorms

Although Shepherd spent years walking into the Cairngorms, she understood she would never know them completely.

The capacity of the mountain to keep its secrets and spring surprises always intrigued her.

One of those secrets was a tiny body of water tucked under a ring of cliffs, 3,000ft above sea level and miles from the nearest road - Loch Coire an Lochain.

She wrote: "It cannot be seen until one stands almost on its lip, the inaccessibility of this loch is part of its power. Silence belongs to it."

For Robert Macfarlane, Nan Shepherd's The Living Mountain is "one of the most brilliant works of modern landscape literature".

He says: "To my mind, no-one has written as well as Shepherd about what it feels like to be in the mountains."