Election 2015: Keep taking the pastilles

- Published

Understandably, our political leaders are beginning to sound - occasionally - a little hoarse. I sympathise: my own consumption of throat pastilles has increased measurably.

However, it is to be hoped that their various voices last out. They may have a bit of talking to do after the election is over. To each other.

Labour's leader Ed Miliband has now ruled out any species of dealing with the SNP. This, of course, builds upon his previous disdain for a formal coalition.

It is to be presumed that Mr Miliband calculates that the Conservative campaign on this issue, aimed at the good and sensible people of England, has the potential to make a difference to the electoral outcome. That would explain his altered emphasis. An SNP deal with the Tories has already been discounted, by both.

This leaves a range of options. One party may win outright, although polls suggest that is unlikely. Either the Conservatives or Labour may seek coalition or an arrangement with another party, perhaps the Liberal Democrats. Or one of the big parties may attempt to govern as a minority, seeking support on individual issues.

Such a situation prevailed at Holyrood from 2007 to 2011. Despite their own initial doubts, the SNP found they could govern - while making concessions to other parties in individual deals, notably over the budget. Which gives leverage, if not overt power, to those other parties. Such would also be the case at Westminster.

Public opinion

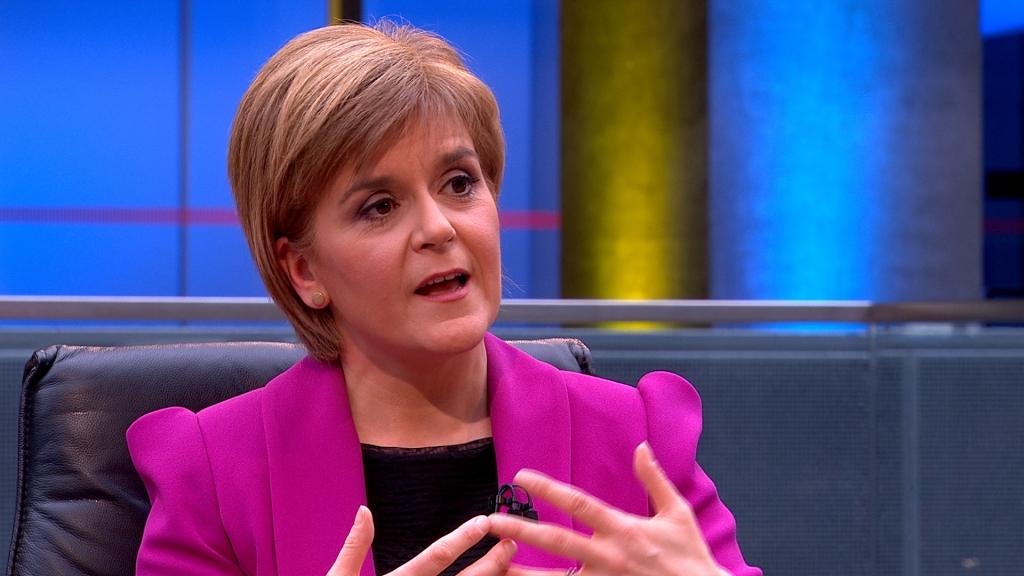

In response, Nicola Sturgeon, the SNP leader, says tonight in a BBC interview that Mr Miliband should not be bullied by the Tories. Len McCluskey, the Unite leader, notes approvingly - and unhelpfully for Mr Miliband - that elements of the SNP's programme to oppose austerity appear to meet his union's wishes.

To stress, again, this debate - while ostensibly about Scottish politics - is in practice about English public opinion. David Cameron is seeking to galvanise voters in England to turn to his party by scaring them with the prospect of Labour / Caledonian rule. Mr Miliband is trying to counter any such tendency.

The Liberal Democrats pitch in by offering a plague on both the Tory and SNP houses. The Tories, according to Charles Kennedy, are jeopardising the union to bolster their own party's hopes. The SNP, again according to Mr Kennedy, are going back on the notion that an independence referendum is a once in a generation event.

A broader question. Is it helpful or even legitimate for so much focus to be upon post-election scenario gaming?

I would argue that it is - as long as it is firmly placed in the context of distinctive and substantive policy offers by the various parties involved. Policy first, strategy second.

Tactical voting

Folk vote for a range of reasons. Personal and partisan. Driven by local circumstances, driven by global concerns. They may like or dislike an individual candidate. They may love or loathe a party leader.

Politics is not neat and simple. It does not operate in precise silos. Tactical voting has to be taken into consideration.

Partly, this is because we operate a parliamentary system. People are voting only indirectly for the UK government (or, at Holyrood, for the Scottish government.) Their direct vote, in Westminster elections, is for a constituency representative.

It is only once the composite verdict has been delivered that we can gauge which party - or parties - will form the UK administration. Which party leader can expect a call from the Palace.

Customarily, in UK elections, the verdict is evident. This time around it may not be so obvious. Hence, the prospect of post poll talks. Hence, the discussion now of what might be regarded by the voters as feasible and reasonable.

Keep taking the pastilles.

- Published27 April 2015