Alberto Salazar and the Nike Oregon Project

- Published

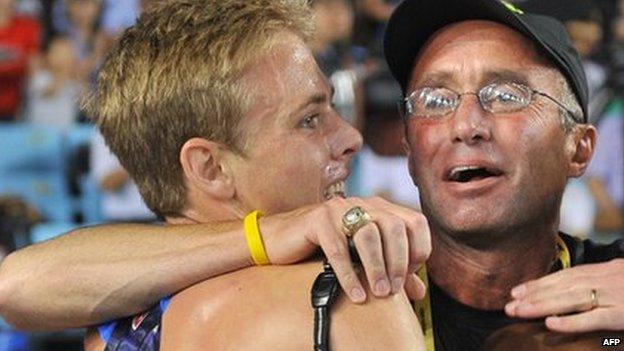

Alberto Salazar with Galen Rupp after the 10,000m Olympic final in London

The final of the 10,000m at the London Olympics 2012 was the pinnacle for the world's most prestigious running group.

The Nike Oregon Project (NOP) scored a historic one-two as its two biggest stars - Mo Farah and his friend and training partner, the American Galen Rupp - left a field of east Africans trailing in their wake.

Watching from side of the track was the architect of this triumph, NOP head coach Alberto Salazar, widely believed to be one of the most powerful coaches in US track and field.

As a coach, he embraces the latest innovations - altitude tents fitted around the beds of his top athletes, long sessions on underwater and zero gravity treadmills - but it was his track record which lured Farah to the project's base in Portland, Oregon, in 2011.

The body which runs the sport in Britain, UK Athletics, was so impressed by Salazar that it hired him in 2013 as consultant to its endurance programme, a position he holds today.

There is no suggestion Farah has used banned drugs or violated anti-doping rules.

But the methods of the man who coached him to glory are now under scrutiny after a number of Salazar's former athletes and staff spoke out.

For more than a year I have been investigating this story, collaborating with the US Investigative journalism outfit ProPublica. The allegations range from the abuse of banned steroids, to subverting the Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) process, in which an athlete can apply to use a banned drug or method if there is a genuine medical need.

If proved, both offences would result in lengthy bans.

Salazar, who strenuously denies any wrongdoing, is also accused of giving athletes prescription medications that they either did not need or were not prescribed in the hope that a competitive advantage could be gained. Alberto Salazar and Galen Rupp were invited to be interviewed. They declined but provided statements.

The allegations come at a pivotal time for athletics, a sport reeling from recent traumas such as the Russian athletics whistleblower scandal and a spate of positive drugs tests in endurance events.

THE PROJECT

The Nike Oregon Project was set up in 2001. It was the brainchild of Alberto Salazar, and bankrolled by Nike. It had the financial backing to match its ambition.

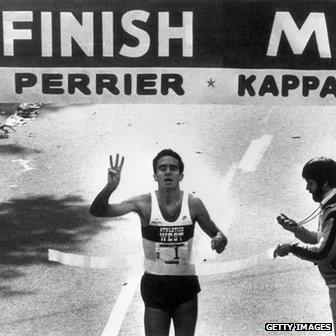

Salazar helped establish the Nike Oregon Project and has a building on the campus named after him

Salazar was an American running legend, embedded into the DNA of Nike; he even has a building named after him in the sprawling Nike campus in Oregon.

He won the New York marathon three years in a row and ran himself unconscious in winning the Boston marathon in 1982.

When NOP launched, its intention was to utilise American talent to challenge the dominance of the east Africans in the distance events - and Salazar had discovered the figure around which the project would be based, a 15-year-old from Oregon called Galen Rupp.

Rupp was the quintessential American "high school phenom".

"I wanted to start the Oregon Project with the best available professional runners, but ultimately, Galen was going to be the star," Salazar later explained in his autobiography.

THE TRAINING PARTNER

Stuart Eagon, also from Portland, Oregon, was a friend of Rupp's. He was not part of the project but raced against and trained with Rupp.

Now 28 and a documentary maker, Eagon told me about an incident in 2003 involving a drug called prednisone.

A glucocorticoid, prednisone can block pain and enhance oxygen consumption, making it a prohibited substance during competition under the World Anti-Doping Agency's (Wada) rules without a TUE, elite sport's version of a sick note.

"Galen, myself and Alberto were outside a hotel room in North Carolina for the national two-mile high school championships," recalled Eagon.

Galen Rupp and Sean Eagon in 2003

"We were going on our morning run and Alberto said to Galen: 'Have you taken your prednisone yet this morning?'"

Eagon knew it was a powerful drug because his grandmother had been taking it.

"Galen went back up to the room, took the prednisone, or so I assumed - we just waited for about 10 minutes - came back down and we went on the run."

Eagon says he was surprised a 17-year-old could be on prednisone but did not appear to be ill.

Two years later, at a race in France, Eagon says he raised it with Rupp, who denied being on prednisone.

"After that I felt as though the dynamic of our relationship changed," said Eagon.

I have heard from various sources that Rupp has used prednisone regularly, but he has asthma and allergies, which could account for its use.

When asked about TUEs, Rupp told the BBC: "Earlier in my career, Wada required TUEs for my asthma medication.

"The few other TUEs I have applied for and received related to the treatment of severe asthma flare-ups."

Alberto Salazar added: "Galen only took prednisone when needed to treat an asthma flare up…under the direction of his doctor for a limited period of time".

THE MASSAGE THERAPIST

John Stiner is a massage therapist who spent time at Park City in Utah, a high-altitude base popular with Salazar's NOP athletes.

Stiner says he worked with Salazar's group for several weeks in 2008, shortly before the US Olympic trials.

After the group, which included Rupp, left, Stiner said Salazar called him up.

"Alberto contacted me and requested that we go up and clean up the [apartments]," said Stiner.

John Stiner said he was asked to post testosterone gel from the training camp in Utah to Salazar in Oregon

"[There were) some products that he wanted us to ship back to him. He said: 'I don't want you to get the wrong idea.'

"I was really unsure what he meant and he goes: 'There's a tube of Androgel [testosterone gel] in the bedroom and it's under some clothing.'"

Stiner says Salazar asked him to post the testosterone gel back to him in Oregon, and said it was for his own personal use because he had a heart condition.

"I kind of thought a little bit like: 'Really?' Because he had just had his heart attack the year before, and I thought that was a little strange.

"So I Googled it and it said 'contra-indicated for anybody with a heart condition'."

The BBC and ProPublica spoke to several cardiologists about whether it was likely testosterone would be prescribed for anybody with a heart condition. All said it would be highly unusual.

Stiner was not the only person telling this story.

Allan Kupscak, another massage therapist who worked with the project for several years, said testosterone gel was seen regularly around the athletes.

Kupscak told me he'd been fired in 2011 after NOP deemed him to have breached his contract.

He said: "When we would travel, at the airport or something, Alberto let it be known to everyone, all the athletes, not to touch his bag, because he had his testosterone cream, for his personal use, in there,"

He added: "If you're worried about someone touching it and possibly getting contaminated, why don't you take it in tablet form or some other form?"

Wada, the body in charge of global anti-doping efforts, says athlete support personnel carrying banned substances without acceptable justification are guilty of a breach and liable for a two-year ban.

Salazar did not respond to questions about this but he did reassert his commitment to "clean sport".

"I believe in a methodical, dedicated approach to training and have never, nor ever will, endorse the use of banned substances."

THE YOUNG COACH

A former assistant coach to Alberto Salazar says he saw a document which said US distance runner Galen Rupp was on testosterone medication in 2002, claims which both Rupp and Salazar deny

Steve Magness was just 25, starting to make his name as a coach, when the call came.

When Salazar first phoned him Magness thought it was a joke, but it soon became clear that the coaching legend wanted the young man to be his number two.

Steve Magness became a coach after his athletics career ended prematurely because of injury

"[But] during that first track season I started getting hints that this might not be what I'd signed up for," he said.

Magness had a story to tell that he claimed connected Salazar, Rupp and the head physiologist of the on-campus Nike laboratory, Dr Loren Myhre. And he had a document.

Magness shared an office with Salazar and one day in 2011 a batch of lab reports were delivered to Salazar's desk from the lab. They contained years' worth of athletes' blood tests, which were used to see how runners responded to altitude training. Magness looked through them.

When he came to a page charting Rupp's results, he said he was stunned to find a note which related to a period in 2002 when the 16-year-old Rupp was still in high school.

It indicated Rupp was "presently on prednisone and testosterone medication".

Magness was already aware Rupp used prednisone - and had separate concerns about that - but he knew testosterone was in a different league.

"That was incredibly shocking," he said.

"I actually took a picture of it. I wanted to have evidence in case something happened."

He says he confronted Salazar, who said it must be a mistake, blaming the lab's long-standing head physiologist Dr Myhre and his battle with a motor neurone condition.

Dr Myhre died in 2012 but the record Magness asked about was from 2002, a year when Nike gave Dr Myhre an award for his work.

Magness says Salazar said Myhre was "crazy" and "must be mixing it up with something else", but the young coach says he did not buy it, and says Salazar never returned to him with an explanation.

Magness went to the US Anti-Doping Agency with his concerns

In response to the BBC, Salazar said the legal nutritional supplement Testoboost had been incorrectly recorded as "testosterone medication".

He added the "allegations your sources are making are based upon false assumptions and half-truths in an attempt to further their personal agendas".

Both Rupp and Salazar strenuously denied that Rupp ever used testosterone or testosterone medication.

"I am completely against the use of performance-enhancing drugs," said Rupp.

"I have not taken any banned substances and Alberto has never suggested I take a banned substance."

But this was not the only experience Magness says he had which led him to question the use of testosterone in the Salazar camp.

He also shared office space with Salazar's son, Alex, who worked on the Oregon Project.

Magness claims Alex was also occasionally used as a volunteer to test supplements.

But in one instance, Magness says Alex told him he was testing some testosterone gel: rubbing some on, getting tested in the lab, rubbing some more on, getting tested.

Magness and two other sources said the reason Alberto Salazar gave for the testing was to determine how much of the gel it would take to trigger a positive test.

Salazar's apparent explanation was that they wanted to figure out if anybody could sabotage the project by furtively rubbing gel on one of their athletes at a race.

"It seemed ludicrous," said Magness, who said he believed it was really done so they could cheat the tests.

Neither Alex nor Alberto Salazar responded to questions about this, though there is no reason to believe Alex doubted his father's reasoning for doing the tests.

Magness, now head coach of the University of Houston cross-country team and the author of coach's manual "The Science of Running", says he lost faith in his job and by mid-2012 had agreed with Alberto Salazar to quit the project.

Two months later he went to the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) with his concerns.

THE STAR ATHLETES

An athlete formerly coached by top athletics trainer Alberto Salazar tells the BBC why she is speaking out about her experiences under the coach

Kara Goucher was an NOP superstar for seven years and is still America's most famous female distance runner.

Under Salazar's guidance, she won a bronze medal in the 10,000m at the 2007 world championships and has previously only talked about him in glowing terms.

Not anymore.

"He is sort of a win-at-all-costs person and it's hurting the sport," she said, sitting beside her husband and fellow ex-NOP athlete Adam, in their first interview about Salazar since leaving his training stable.

Kara Goucher competing in Daegu

"I was afraid to say anything (but) I'm tired of saying 'I'm off the Oregon Project because I had a baby and I no longer fit in.'"

Goucher claims Salazar breached the spirit of the rules - and US prescription laws - by asking her to take a thyroid drug for which she did not have a prescription in order to lose weight ahead of her comeback race following the birth of her son Colten.

Goucher was already taking one synthetic thyroid hormone, Levoxyl, which she had been prescribed before coming to NOP for an inherited underactive thyroid.

Drug information websites indicate that Cytomel is not to be used in conjunction with other thyroid drugs, or for weight loss, and that large doses "may cause serious harm".

Salazar did not respond to questions about Cytomel but said: "No athlete within the Oregon Project uses a medication against the spirit of the sport we love.

"Any medication taken is done so on the advice and under the supervision of registered medical professionals."

He also added that thyroid medicine is not banned under Wada rules and said he was unaware of any performance-enhancing benefits.

Kara and her husband Adam were both NOP athletes

The Gouchers had another story to tell, claiming they witnessed Rupp and Salazar attempting to subvert the TUE process on two occasions.

At both the 2007 and 2011 Worlds, Kara Goucher said Salazar coached Rupp on how to get medical permission for an intravenous (IV) drip of saline before his races.

She says Salazar told her: "We have it down. I've coached him on what to say. The doctors will ask him when was the last time you go to the bathroom and he'll say I don't remember. They'll say when was the last time you were able to drink and he'll say I can't."

Its performance enhancing benefits are not proven, but Wada has banned the practice of IV drips, and anyone proved manipulating the system to try to get one is liable for a ban.

Goucher says she does not know why they wanted the IV drip in Osaka and Daegu but says "they were manipulating the system to get it".

Salazar responded: "I have never coached an athlete to manipulate testing procedures or undermine the rules that govern our sport…and follow the process."

THE ANTI-DOPERS

The Gouchers left NOP in 2011, though Kara remained a Nike-sponsored athlete.

In 2013, while still a Nike athlete, Kara took her concerns to Usada with her by-then retired husband Adam. They addressed them to Usada's boss Travis Tygart, the man who brought down Armstrong.

The BBC is aware of at least seven athletes or staff associated with NOP who say they have gone to Usada with concerns about alleged illicit practices and unethical behaviour.

Usada did not confirm or deny the existence of any investigations but said it "takes all reports of doping seriously and we aggressively follow up on every report".

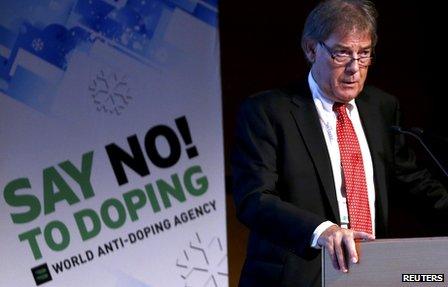

Wada chief executive David Howman said he was "disturbed" by the allegations

I took the allegations to Wada's headquarters in Montreal.

In an interview with its chief executive David Howman, I asked about the claim that Rupp was given testosterone in high school.

"It doesn't matter who the coach is or who the athlete is, that behaviour is not condoned," said Howman.

Asked if he was concerned by the allegations, he said: "I would be not only disturbed, I would be very disappointed and that's why I think it needs to be scrutinised by us as an independent body."

None of the insiders I spoke to has seen any evidence that Mo Farah was doping. But do these allegations raise questions about his choice of coach?

I showed them to Andy Parkinson, the former head of UK Anti Doping.

He said: "On the basis of the allegations that you've shown me … any athlete who's involved or associated with this group, including Mo Farah, should be seeking the necessary assurances around the fact that they're operating within a safe environment.

"Athletes have got a responsibility to…ask the question of themselves, do I feel comfortable in this environment and am I going to be able to continue to compete clean in this environment?"

Mo Farah said: "I have not taken any banned substances and Alberto has never suggested that I take a banned substance.

"From my experience, Alberto and the Oregon Project have always strictly followed Wada rules."

Catch Me If You Can will be shown on BBC1 at 2100 on Wednesday, and afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published3 June 2015

- Published5 June 2015