Lancastria: The forgotten tragedy of World War Two

- Published

Seventy five years after the sinking of the Lancastria - Britain's worst maritime disaster in history - why is the tragedy largely forgotten? And what do those touched by the catastrophe want now?

"The trouble with the story of the Lancastria is it doesn't fit with the grand narrative of that period - the miraculous evacuation of Dunkirk, and the Battle of Britain," reflects Mark Hirst.

"No amount of spin can turn the story of the Lancastria into something triumphant."

Mark - a former broadcast journalist and co-founder of the Lancastria Association of Scotland - has studied the life of his grandfather Walter Hirst, who survived the sinking.

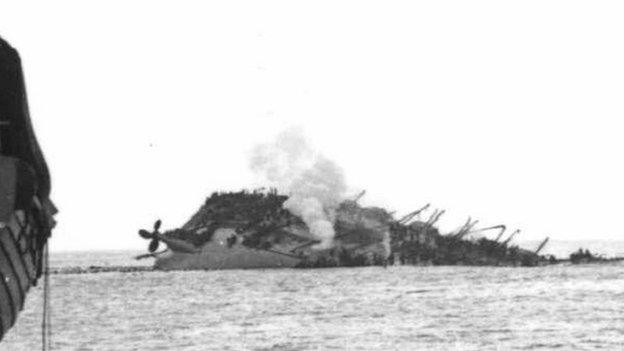

About 4,000 men, women and children lost their lives when the Lancastria sank 20 minutes after it was bombed by the Germans near the French port of Saint-Nazaire on 17 June 1940. Fewer than 2,500 people survived.

The Lancastria was the largest loss of life from a single engagement for British forces in World War Two and is also the largest loss of life in British maritime history - greater than the Titanic and Lusitania combined. But it is a largely forgotten chapter in British history, a fact that leaves survivors and relatives aggrieved.

Walter Hirst hardly spoke to his family about the Lancastria

On the day the Lancastria sank, Walter - who was from Dundee and serving with the Royal Engineers - was in the company of his friend Charlie Napier from Inverurie.

It was a few weeks after the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk, and Walter and Charlie were still in occupied Europe with an estimated 150,000 other British servicemen.

The Lancastria was tasked to bring them home.

Mark, a filmmaker, has spent years researching the next few hours of his grandfather's life. He believes Walter and Charlie found some life jackets on the Lancastria to use as pillows on the way home.

When Nazi planes dropped their bombs, Walter and Charlie were separated in the chaos.

Walter ended up in the water and saw a dog swimming away from the wreckage. It is thought this dog may have belonged to two refugee children, who had boarded the Lancastria after walking through Belgium and France for weeks with the animal.

Walter managed to hold on before the animal disappeared.

With the sea thick with oil, German planes strafed survivors trying to keep afloat.

Walter was attacked by a man who wanted his life jacket. In the words of Mark, his grandfather's fight ended when the "mad man sank beneath the waves".

"I think my grandfather was haunted by that," added Mark. "I think that is probably the reason he never went to any of the company reunions. I think he was embarrassed. He was a very quiet man, and his recalling of the Lancastria tended to come only after a couple of pints."

News blackout

Walter was in the water for around four hours before he was picked up. When he eventually returned to England, he was ordered - along with the other survivors - to not speak a word about the Lancastria.

He never saw his friend Charlie again. Walter assumed, to his dying day in 1989, that Charlie was killed in the sinking.

But Charlie had also survived. Years later, he helped Mark to piece together the stories of the Lancastria. He passed away four years ago, the last Scottish survivor to die.

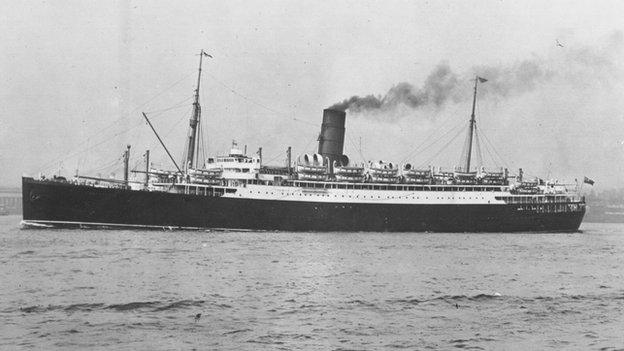

The Lancastria was a Cunard liner before the Second World War

Winston Churchill ordered a media blackout on the sinking

Following the sinking of the Lancastria, Prime Minister Winston Churchill imposed a media blackout. The government feared what the news would do the British nation in the midst of its darkest hour.

Eventually, newspapers in New York broke the story at the end of July - five weeks after the disaster. Even then, the British newspapers toed the patriotic line.

The late edition of The Scotsman on July 25 1940 featured a six-paragraph story buried on the middle of page five. It highlighted claims from the New York Sun newspaper on the sinking, with 500 feared dead.

In the following day's paper, again on page five, there was a more detailed article.

"Nearly 2,500 are known to have been saved - and more may be in enemy hands - from a total 5300 aboard the transport Lancastria, which, it was admitted in London yesterday, was sunk on June 17 by the enemy during the evacuation of the BEF from France,' it read.

The article said the soldiers sang popular World War Two songs "Roll Out the Barrel" and "There'll Always be an England" as the ship went down. Other soldiers, meanwhile, performed acts of bravery and helped civilians while there was "no panic".

Survivors of the Lancastria, who were all ordered not to talk about the sinking

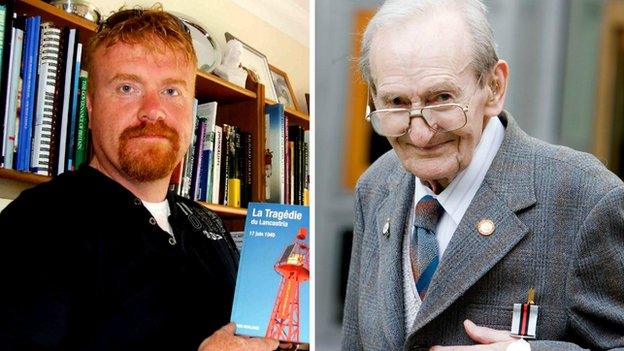

Mark Hirst (left) became friends with Charlie Napier (right), who served with Mark's grandfather Walter

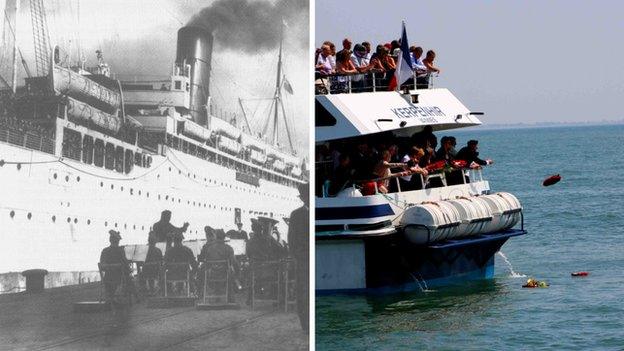

The Lancastria, pictured in Greenock, and its resting place in French waters

Seventy five years on, and despite a special Scottish government medal for Lancastria survivors and their families, relatives want the sinking to be properly remembered.

They question why, after all this time, the area of the sinking - which is in French waters - is not designated a British war memorial site. Furthermore, some believe the British government have not revealed all documentary evidence of what happened.

In a letter to The Times last month, campaigners said the government should do more.

The letter added: "These relatives do not have a clear understanding of what happened as documentary evidence, they are told, remains unavailable; and possibly will not be revealed until 2040, which is of no comfort; indeed it adds to their distress as the relatives, themselves, will not be alive."

Mark said: "There is a definite residual sense of grievance. The initial cover up at the time of the war is perhaps understandable, because it could be used as propaganda by the Germans.

"But the lack of recognition and acknowledgement in the subsequent years that has left many survivors and relatives of victims feeling their sacrifice was worth less than the big heroic events of the Second World War."

Jacqueline Tanner is one of a handful of people who was on the Lancastria and is still alive. She was two and a half when the ship was attacked.

Her parents Clifford and Vera Tillyer were working in Belgium when they decided to evacuate. When the Lancastria was hit, Jacqueline's family managed to escape by running through the ship shouting "baby here, baby here".

When they reached the water, Jacqueline was kept alive on a floating plank of wood.

Jacqueline Tanner (centre), with her father Clifford and mother Vera, pictured drinking tea in Plymouth after being rescued from the Lancastria

Jacqueline, pictured in 1949 as she laid a wreath at the cenotaph in Whitehall on behalf of the Lancastria Survivors Association

The Lancastria memorial in the grounds of the Golden Jubilee Hospital in Clydebank

Now aged 77 and living in Malvern, Worcestershire, she will be joined by her husband, her children and her grandchildren at a ceremony in Saint-Nazaire on 17 June to mark the tragedy.

"We want recognition that this was the biggest sea disaster ever," she said.

"When we have tried, they (the government) have said it (documents on the Lancastria) are secret. I can't think, after all of these years, it can still be a secret.

"It was a bad time - the evacuation from France. I think Churchill was right when he said 'we don't broadcast this'. It was too much for the people to take. Surely, after all of these years now, it can come out. Why don't they recognise it? We don't know."

The Ministry of Defence said all known documents relating to the Lancastria have been available at the National Archives at Kew since the early 1970s.

A spokesman added: "The sinking of the HMT Lancastria remains the United Kingdom's greatest maritime disaster and, although it occurred over 70 years ago, the sacrifice of many thousands of servicemen and civilians, and the endurance of those who were saved that day, must never be forgotten.

"As the French Government has provided an appropriate level of protection to the Lancastria through French law and it is formally considered a military maritime grave by the MoD, we believe that the wreck has the formal status and protection it deserves."

On Saturday, 13 June, relatives of those who were on the Lancastria will gather for a ceremony at the Scottish memorial at the Golden Jubilee Hospital in Clydebank, near to where the ship was built.

Many will then travel to France for the service at Saint-Nazaire on Wednesday, with no major event planned in the UK. The MoD has said it does not plan to send a representative to France.

As the families reflect on their loss, it appears their frustrations will remain.

- Published29 May 2015

- Published5 April 2015

- Published1 October 2011