Keir Hardie - The man who broke the mould of British politics

- Published

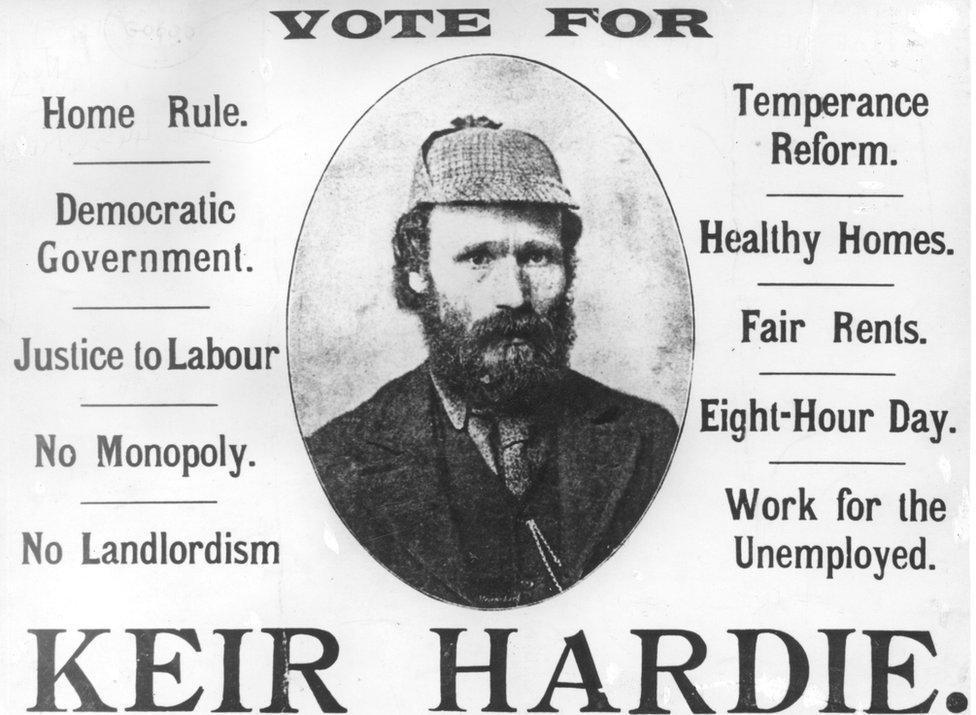

An election campaign poster from about 1895

When James Keir Hardie died on 26 September 1915 he was reviled by much of the political establishment but the past 100 years have seen his reputation grow as the man who broke the mould of British politics.

He was the first working class socialist MP and the first leader of the Labour Party in the UK parliament yet when he passed away not one word of tribute was paid to him in the House of Commons.

No representatives from any other political party appear to have attended his funeral in Glasgow.

Newspaper tributes were hostile and unforgiving, with one saying he was one of the most hated men of his time.

Keir Hardie died virtually penniless and a public appeal had to be launched to help his family.

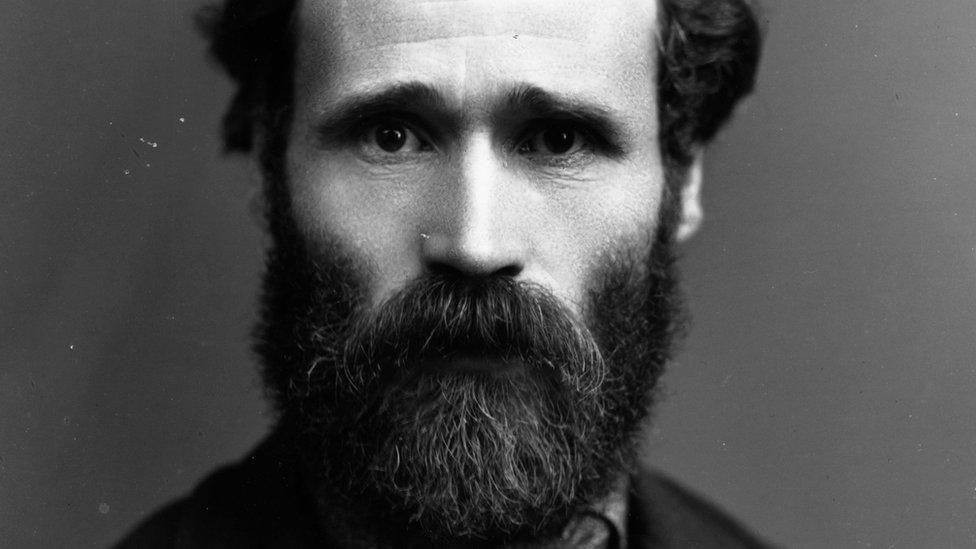

James Keir Hardie in 1892

However, by 1956 a statue of him was placed in the House of Commons.

At the time, Clement Atlee, the post-war Labour prime minister, said: "Mr Speaker, I think this is the first time that a bust has been placed in the House of Commons of a member of the working class.

"Hardie was not only born of the working class, he remained of the working class."

Atlee added: "Few members of parliament had a greater effect upon the House of Commons than Keir Hardie.

"Before the end of the 19th Century parliament consumed itself very little with the life of the common people of our country.

"The turning point came at the end of that century and Hardie symbolised that change."

Hardie's life began in great poverty.

He was born illegitimate on 15 August 1856, near Newhouse in Lanarkshire, the son of Mary Keir, a domestic servant, and William Aitken, a miner who wanted nothing to do with him.

Soon Mary Keir married David Hardie, a ship's carpenter, and James Keir took his stepfather's name and became James Keir Hardie.

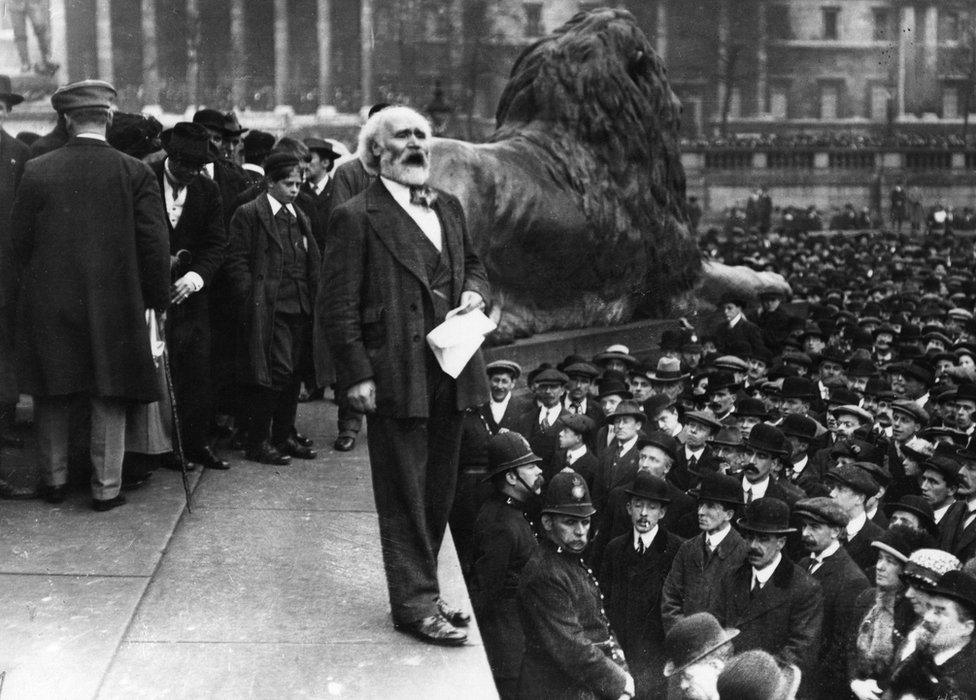

Hardie waiting to address a crowd during the Tailors' Strike in 1912

The family had to move from place to place as his stepfather failed to find regular employment and their poverty forced young Hardie out to work at the age of eight - first as a message boy, then at a bakery, then heating rivets in a shipyard where the boy next to him fell off a scaffold and was killed.

In desperation, his father returned to work at sea. His mother moved back to Lanarkshire and at the age of 10, Hardie went down the mines where he worked as a "trapper", operating the ventilation doors deep underground.

"I am of the unfortunate class who never knew what it was to be a child," Hardie wrote.

"For several years as a child I rarely saw daylight during the winter months.

"Down the pit by six in the morning and not leaving it again until half past five meant not seeing the sun."

Keir Hardie addressing the Suffragettes' Free Speech meeting in Trafalgar Square in 1913

Hardie had no formal schooling but his mother spent evenings patiently teaching him to read and write.

And because of his stepfather's drinking, his mother steered the young Hardie towards the temperance movement.

In his teenage years he was a member of the evangelical union in Hamilton, an organisation with strong links to the temperance movement.

His preaching helped him learn the art of public speaking and the mine workers of the area soon co-opted him to speak for their grievances.

"He described himself as an agitator," says Melissa Benn, writer and honorary president of the Keir Hardie Society.

Bitter strike

His agitating got him banned by mine owners from working in the pits in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire but instead he turned his attentions to organising the miners in a trade union.

He led a bitter strike in Lanarkshire which failed, but then accepted a call to relocate to Cumnock in Ayrshire to organise miners there.

Hardie had been a supporter of the Liberal Party but when in 1887 a miners' strike in Lanarkshire was broken because the iron companies imported the police into the coal field he decided radical action was needed.

Warwick University lecturer Fred Reid says Hardie was "absolutely furious" and realised the Liberal Party was not going to deliver fundamental social change.

In a series of editorials in the Miner, a magazine that Hardie set up, he declared his new vision.

Reid says: "Hardie says we need a Labour Party, pure and simple."

"He says in the same editorial it should have two aims.

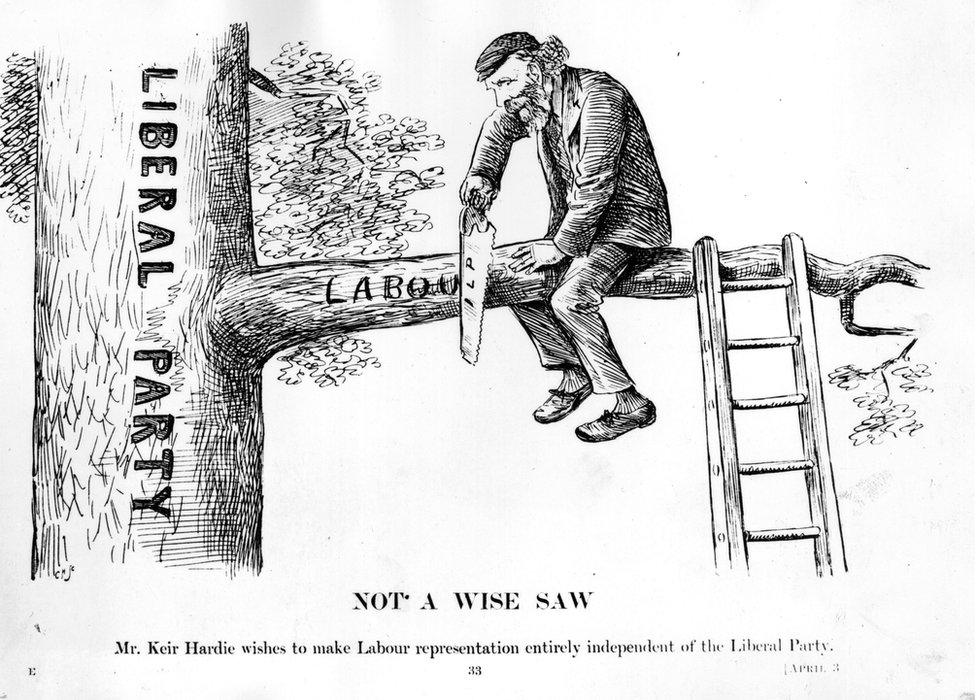

A cartoon from 1893 when Keir Hardie formed the Independent Labour Party, by Francis Carruthers Gould

"The first is it should aim to replace the historic Liberal Party and the second thing is he lays down a programme for this new party.

"It includes the legal minimum wage and the legal eight-hour day and it includes the nationalisation of the mines, minerals and railways."

He tried to get elected to parliament in a Scottish seat but instead he finally succeeded in becoming an MP in West Ham in London in 1892.

He became known as the member for the unemployed and helped create the Independent Labour Party in 1893.

Keir Hardie caused consternation by entering parliament in a "cloth cap" at a time where everyone else wore a top hat.

A year later he became even more controversial when, after a mining disaster in Wales, he tried to amend the statement following the birth of the prince who would become Edward VIII with a message of condolence to miners families.

No-one would second his motion and the speech made him deeply unpopular and may have contributed to him losing his seat in West Ham in 1895.

Keir Hardie in 1914

He re-entered parliament as MP for Merthyr Tydfil in 1900.

Hardie became increasingly disgusted by the behaviour of fellow MPs.

He wrote: "More and more the House of Commons tends to become a putrid mass of corruption, a quagmire of sordid madness, a conglomeration of mercenary spiritless hacks dead alike to honour and self-respect."

So determined was Hardie to deliver a Labour Party in parliament that in 1904, he and Ramsay Macdonald, the future Labour prime minister, made a secret electoral pact with the Liberal Party and, as a result, 29 Labour MPs were elected in 1906.

The parliamentary Labour Party was formed and Keir Hardie became its first leader.

He toured the country campaigning for the new Labour party but years of travel round the country had taken its toll.

Hardie suffered a breakdown in his health and resigned as Labour leader in 1908.

He continued to support causes such as votes for women.

The disappointment of the outbreak of World War One had a great affect on him, destroying his ideas of a universal brotherhood of men in Europe.

Within a few days of Britain going into the war he was speaking at his own constituency and he was shouted down by the crowd who supported the war.

He died on 26 September 1915, aged only 59.

Keir Hardie; Working Class hero is on BBC Parliament at 20:40 BST on Saturday 26 September and on Sunday 27 September at 10:40 BST.