The man who almost had the Wright stuff

- Published

Britain's oldest aeroplane is being restored in Edinburgh by the National Museums of Scotland.

The Hawk was the work of the Scottish-based pioneer Percy Pilcher. The glider was a record-breaker 120 years ago and was flown by the first woman pilot.

According to many sources, Pilcher was born on 16 January, 150 years ago.

His plane will to be a key exhibit when new galleries open this summer at the National Museum in the capital's Chambers Street.

It is a thing of fragile beauty, both a historical artefact and a work of art.

Pilcher's Hawk currently resides at the National Museums of Scotland (NMS) collection centre near the Forth shore in Edinburgh.

Think of it as the museums' cupboard under the stairs: a complex of buildings where exhibits are prepared for display or at the very least preserved for future generations to study.

Percy Pilcher's Hawk, Britain's oldest aircraft, is ready to go on public display

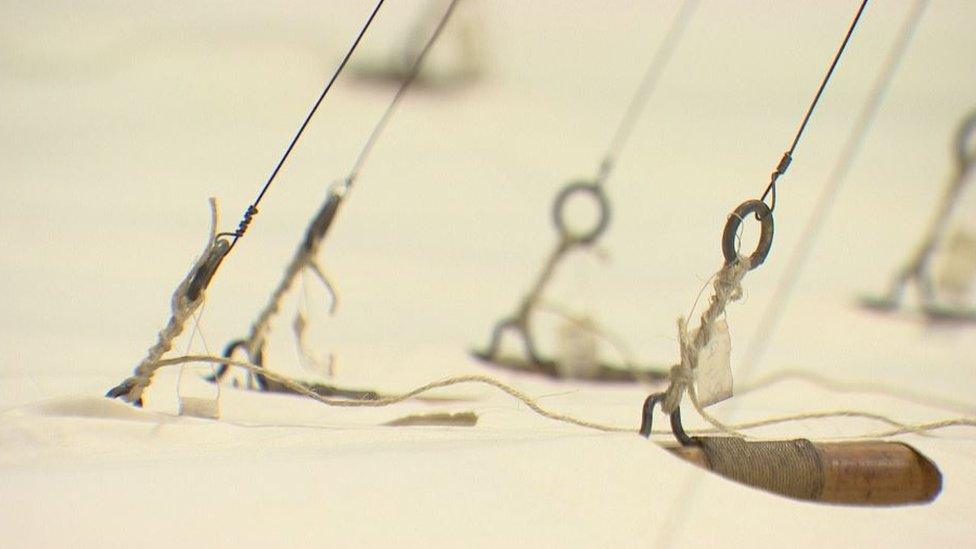

The Hawk looks a bit like a giant bat - if you could build a bat out of bamboo poles, iron wire and cotton sailcloth.

It really flew - there are photographs to prove it - and at 120 years old, it is Britain's oldest surviving aircraft.

It was designed, built and flown by Pilcher. He also died in it.

This was all before the dawn of the 20th Century. Becoming an aviator was not widely regarded as a career option. Barring the odd balloonist or gliding pioneer there weren't many of them about.

Instead, Pilcher became a nautical engineer. He was born in Bath and served his time in a Govan shipyard.

By the time the 19th Century was drawing to its close, he had become an assistant lecturer at Glasgow University. It was during that time that his interest shifted from the waves to the air.

He became fascinated by the way in which some other animals could fly. Why not humans?

That fascination took physical form in a series of gliders of increasing sophistication: The Bat, The Beetle, The Gull.

He rented a farmhouse near Helensburgh where he could fly them. The concept of control surfaces had not yet been developed so he piloted each aircraft like a hang glider pilot does now, twisting his body to shift his weight.

The Hawk was to be his last glider before he moved on to powered flight.

"He was building it in his lodgings in Hillhead in Glasgow," said Louise Innes, the principal curator of transport at the NMS.

"When this one [The Hawk] was completed in March 1896 you can see him on Kelvingrove Park, assembling it with his sister Ella."

The photos show Ella in the fashion of the day - long skirt, heavy jacket, hat piled with flowers. She is looking somewhat disapprovingly at the camera.

It was Ella who sewed the sailcloth to create the Hawk's wings. So far, so in line with the gender stereotyping of the day.

But Ms Innes says Ella and another member of the Pilcher family have a more important place in the history of women in aviation.

"When he flew it in June 1897, his cousin Dorothy became the first ever woman to fly in a heavier-than-air aircraft.

"That's not a balloon, that's an aeroplane. It was a world first.

"His sister Ella also flew it. So two women flew this aircraft in the 19th Century."

There's an understandable note of pride in her voice. Ms Innes is a glider pilot herself.

Several replicas of Pilcher's hang gliders have been built but the NMS has the real Hawk.

Remarkably, it's survived for 120 years and Gemma Thorns has spent well over a year making it fit for the 21st Century.

She's an assistant conservator in the engineering and furniture department which, given it's an aircraft made of bamboo and cotton, brings together those two otherwise contrasting disciplines.

Her work has involved removing years of grime and treating corrosion of the iron wires.

It has also meant correcting the mistakes of previous restorers.

"The sails that were on it weren't the original sails. They were put on in the 60s," Ms Thorns says.

"We decided they were too deteriorated to be placed safely on display. So we decided to remove them and make new sails.

"Which is also good because the sails were actually not on correctly."

An earlier restoration had put the sails underneath the wings' bamboo ribs. Ms Thorns has put them back on top.

That means the original Hawk is now correctly rigged but replicas that imitated the earlier restoration job still have them the wrong way up.

By the time he was 32, Pilcher was a record breaker. He had flown The Hawk to a world distance record for a heavier than air machine, a whopping 250m (273yds).

Sadly he didn't reach 33.

He had built a new powered triplane he was planning to demonstrate to potential backers. But at the last minute the engine failed and Percy instead elected to take the now obsolete Hawk up for one final flight.

It had been a stormy day but Pilcher thought the conditions would be good enough. But The Hawk's tail broke off and he fell, dying of his injuries two days later.

We'll never know whether he could have beaten the Wright Brothers to the first powered, controlled flight.

Instead, he will remain one of aviation's great might-have-beens.

The Hawk has one final journey to make - to the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh's Chambers Street. It'll be one of five historic aircraft hanging in the atrium when 10 new galleries open this summer.

Perhaps then, 150 years after he was born, it will be time to give Percy Pilcher the place he deserves in aviation history.

- Published15 January 2016

- Published15 January 2016