Dorothée Pullinger: The pioneer who built a car for women, by women

- Published

Engineer Dorothée Pullinger designed the 1924 Galloway car specifically for women

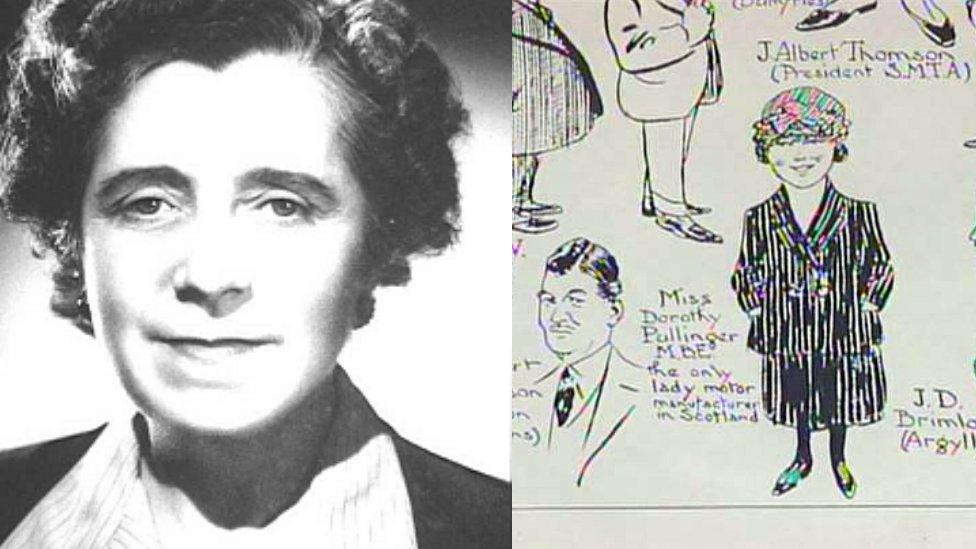

The story of pioneering car engineer Dorothée Pullinger is being told in a new exhibition in Glasgow's Riverside Museum. She is best remembered for the development of the Galloway car, which was made by women in south west Scotland for the women of the world.

The Galloway is thought to be one of the first times in history a car was manufactured with women specifically in mind. Dorothée and her workers did it at a time when the world of engineering was the domain of men.

Dr Nina Baker is a Glasgow councillor and engineering enthusiast. In 2012, she inducted Dorothée into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame., external

She said: "Although there are many women who were working in engineering before and after Dorothée Pullinger, and are often commemorated as pioneers of women getting into a man's world, she is unique.

"She made a significant contribution to engineering which stands up to other male engineers of her period."

The Galloway 10.5 Coupe model, built at Heathhall in 1924. Located at the Riverside Museum in Glasgow, it is the only Galloway on public display in the UK.

Dorothée was born in France in January, 1894. Her father was the car designer Thomas Pullinger.

The family moved to the UK and Dorothée was educated in Loughborough. By 1910, she was keen to follow in her father's footsteps and started work as a draughtswoman at the Paisley works of Arrol-Johnston, a car manufacturer where her father served as manager.

Dorothée's children believe their mother had it tough in Edwardian Britain.

"Life is a challenge and you go for it," said her 84-year-old son Lewis, speaking to BBC Scotland from his home in Guernsey in 2016.

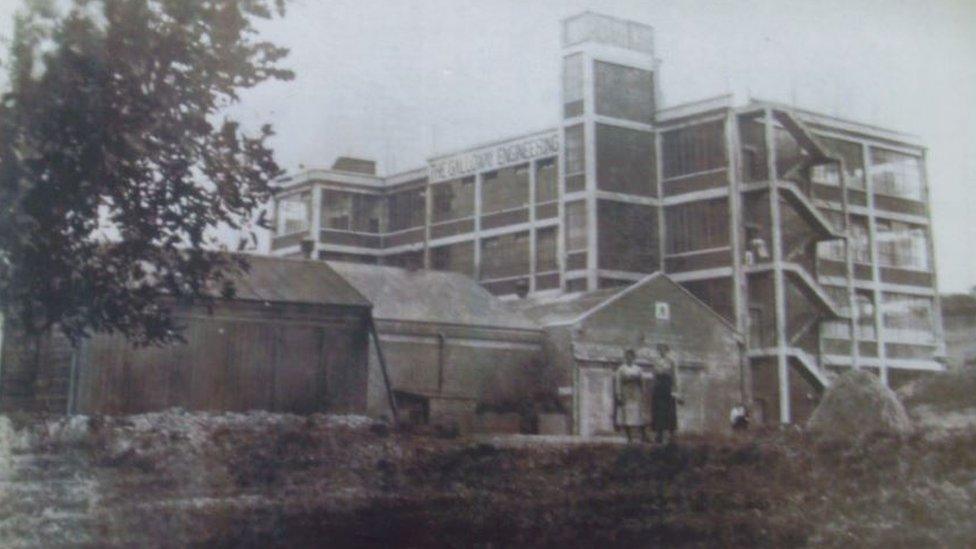

Tongland factory near Kirkcudbright, where Galloway employees played tennis on the roof

"You follow the things you believe in. In her youth, women didn't go into engineering - they were in the house doing the cooking, doing the housework.

"She wanted to do the things that her father did."

Dorothée's daughter, Yvette Le Couvey, said her mother spent a long time convincing Thomas Pullinger to let her work in his field.

"In her day, women just didn't do those sort of things," Yvette added.

In 1914, Dorothée applied to join the Institution of Automobile Engineers. She was refused, on the grounds that "the word person means a man and not a woman".

Dorothée Pullinger pictured with a Galloway car

World War One gave her an opportunity. Dorothée was put in charge of female munitions workers at Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria, producing bombs for the front line. Eventually, she was responsible for an estimated 7,000 workers.

After the conflict, she was finally accepted to the automobile institution as its first female member and awarded an MBE for her war work.

By the 1920s, Dorothée was back to Scotland and to cars. She became manager of the Galloway Motors, a subsidiary of Arrol-Johnston, at its factory in Tongland, near Kirkcudbright.

The factory was originally built during the war to manufacture aeroplane parts, but Dorothée persuaded her father to keep it open as a car factory and provide employment to many local women.

Galloway was no ordinary company. It adopted the colours of the suffragettes, had two tennis courts on its roof for employees, and Dorothée hosted an engineering college there. Apprenticeships lasted three years for women rather than the usual five for men because, it was believed, women were faster learners.

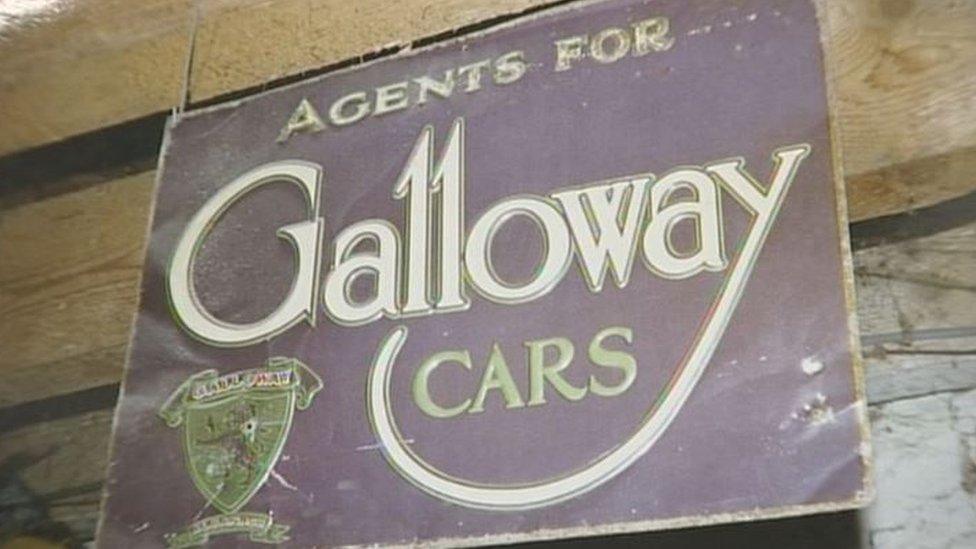

Galloway cars adopted the colours of the suffragettes

Dorothée managed production of the Galloway car, with the designs influenced by her father and by the Fiat 501 model.

The Galloway was described by Light Car and Cycle in 1921 as "a car built by ladies, for those of their own sex".

But what was so different about it?

Nina Baker says: "To understand the differences, you need to have in your mind one of the big clunky cars of the early 20th century.

"They were designed with men in mind. I am about 5ft 4in - a typical height for a woman of that period - and if you sit in one of them, you could hardly reach anything.

"In those days, the gear lever and the brake lever were on the outside of the car - across the doorway. If you were getting into a car with a long skirt, they were a real nuisance."

During the Second World War, workers at the Heathhall plant produced aeroplane parts

The Galloway though was much lighter and smaller. On some models, gears were placed in the middle, the engine was more reliable, the seat was raised, storage space was added, the dashboard was lowered, and the steering wheel was smaller - all with the female driver in mind.

The car was also one of the first automobiles to introduce a rear view mirror as standard.

Dorothée liked to show off the Galloway. She took part in the Scottish Six Day Trials, an event for motorists to demonstrate their vehicles to crowds, with the Galloway winning the event in 1924.

But the 1920s were tough for independent car makers.

Production of the Galloway was moved to the nearby Heathhall works in 1922/23 when Tongland was closed, but within six years the cars were no longer produced.

Dorothée Pullinger (centre in black), with some of her factory workers

Only 4,000 of the vehicles were ever made, with a model in Glasgow's Riverside Museum thought to be the only one on public display in the United Kingdom.

In 2019, a century after Dorothée became a founding member of the Woman's Engineering Society, the museum has now created an exhibition about her.

For Dorothée, she left the car manufacturing business after a spell of working as a sales representative for Arrol-Johnston. According to her children, she eventually became fed up with of people telling her she was "taking a man's job".

She set up the White Service Laundry company in Croydon.

During World War Two, she served her country once again. She was the only woman appointed to the Industrial Panel of the Ministry of Production, addressing post-war industry problems.

Dorothée Pullinger was a woman very much in the man's world of car manufacturing in the early 20th century

After the conflict, she settled in Guernsey and established another laundry business. She passed away in 1986, aged 92.

Now, more than three decades after her death, you can only wonder at what Dorothée would have made of the engineering industry in modern Britain.

Nina Baker believes that Dorothée legacy is "normalising" engineering as a career for women.

"Young women who are not certain if they want to go into engineering, and perhaps feeling they don't want to be isolated as a women in a man's sphere, don't have to necessarily feel that they are that", she says.

Yvette le Couvey, centre, is pictured unveiling a plaque in Barrow-in-Furness for her mother in 1984

For Dorothée's children, she was a just a woman who tried to do the job she loved.

"She realised that the things she had done in her youth helped women for their independence," said Lewis Martin.

"A car for women, designed by women - women are just as capable in many things as men."

"I'm very proud," added daughter Yvette, who is now 93. "She achieved things - how many other women achieved what she achieved? It is all a question about going forward."