Is the time right for Indyref2?

- Published

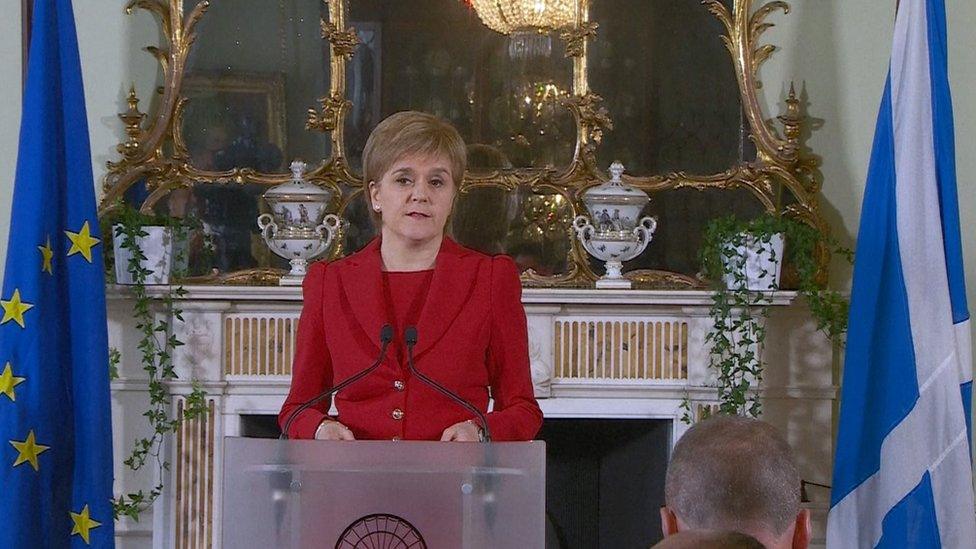

Ms Sturgeon said a second independence referendum was "highly likely"

It looks "highly likely", says Nicola Sturgeon, that there will now be a second referendum upon Scottish independence.

Is she enthused by this prospect? Does she thrill at the notion? Is she buffing up her best lines from 2014? The answers to those questions would be no, no and, once again, no.

To be clear, for the avoidance of any doubt, Nicola Sturgeon remains rather keen on the concept of Scottish independence. Indeed, she yearns for it.

She knows that means another referendum at some point in the future. But not now. Not in these circumstances. Not in these troubled times.

Political leaders, understandably, seek to mould events to their own agenda. They dislike being driven by circumstance. Ms Sturgeon is now in the latter case.

Consider things from another angle. Cast the EU referendum from your mind. Imagine it never happened. (Yes, that's right, just like David Cameron and George Osborne.)

Do you think that - without that EU referendum result - Nicola Sturgeon would now be making legislative plans for indyref2? You do? Behave yourself.

Balancing pressure and pragmatism

Left in first ministerial peace, without European alarums and excursions, Ms Sturgeon would regard a second independence referendum as a mid-term project. Work on that White Paper, especially the currency. Work on the voters. Govern sensibly and consensually meanwhile. Then try again.

She does not now have that option. SNP leaders - Mr Salmond was no different - have to balance the pressure from the party with pragmatism. They hear the cry. "What do you want? Independence! When do you want it? Now!!"

Frankly, they join or lead the chants. But Nicola Sturgeon is also a deeply serious strategist. For the umpteenth time, she does not want to call a referendum. She wants to win one. And she suspects that the immediate environment may not be all that propitious.

But she is now constrained. To win support during the 2014 campaign, it was thought sensible to talk up the choice as being generational - or even once in a lifetime.

To sustain the support of the SNP's more enthusiastic advocates, it was felt necessary to place caveats on the 2014 defeat for the independence cause.

In particular, it was felt appropriate to link those caveats to an issue which had been so dominant in the 2014 campaign itself: that of Scotland's links with the European Union.

The 2014 independence referendum was often described as a "once in a generation" event

To be clear, this is a core element, not remotely peripheral or second order. For decades, the SNP pitch has been that Scotland would not solely be quitting the Union of the UK in pursuing independence but joining the Union that is Europe on equal terms. Not leaving, but joining.

This was fundamental within the offer to the Scottish people. It offered reassurance. Hence the importance attached by the SNP to the growing debate across these islands, prompted by a fretful Conservative leader, over the EU.

Hence the declaration that overturning Britain's - and thus Scotland's - membership of the EU would result in a "material change in circumstances" and possibly indyref2.

However, declaring it as a possibility, forecasting it might happen, does not mean that Nicola Sturgeon wanted such an outcome. To repeat, she did not. She wanted Scotland, Britain, to vote to Remain. She wanted to resume her independence campaigning on her own terms and to her own timescale.

She wanted to choose. That choice has now narrowed. Still, Ms Sturgeon does not finally call an independence referendum. She declares that, prior to that, she will examine alternatives to sustain Scotland's links with the EU.

Not leading, but following

In essence, Ms Sturgeon isolates the Scottish vote from the UK outcome. How would she do any other? She believes firmly, viscerally, that Scotland is a nation and should be a state. Just like other states in membership of the EU.

She believes firmly, viscerally, that she is now mandated, obliged, to seek to implement that Scottish EU verdict, by whatever means are available.

But what might those be? David Cameron has already accepted her demand that Holyrood and the other devolved administrations must be given a role in the EU exit talks. But that would be definitively a devolved role, a subsidiary role. Not leading, but following.

Mr Cameron has announced he will step down by October

She has pressed for direct links between Scotland and EU institutions, without going through the prism of the FCO or the Cabinet Office. But what, in practice, would that mean, other than lobbying and discussion? Would it replicate the current relationship? No.

Might the EU concede membership to Scotland - or associate membership? Scarcely. The EU operates by member states, several of whom are nervous about sub-state autonomous campaigns within their borders. For them, UK out means UK out. The entire UK.

There may be warm words. Contented communautaire conversation. But it is membership which, ultimately, counts. And that points to Scotland seeking to join (or rejoin) on her own right, on negotiated terms. Post independence.

It is possible that the people of Scotland will feel so aggrieved by the EU result that they turn towards independence.

It is equally possible that they feel that the political environment is already sufficiently chaotic and troubled without adding indyref2 into the mix.

Conundrum for Labour

Remember, too, the nature of the core SNP pitch. It is based upon mature confidence, urging Scotland to take back control of her own affairs. (Where have I heard that phrase recently? Ach, it will come back to me.)

It is not based upon flight. It is not based upon escaping tyranny or despotism. It is not based upon a rejection of cultural or physical imperialism, as so many other nationalist offers are. It is different.

Still, it is not always given to political leaders to control the events which shape their decisions. As one remarkable referendum is digested, stand by, in due course, for another.

Ms Sturgeon, of course, is not remotely alone in finding the overnight results a problem. They are a conundrum for Labour; its understated, limpid appeal for Remain rejected in its English heartlands.

They are a challenge for the SNP, seeking to cope with the independence implications. But they are a crisis for the Conservatives whose leader sought to use a plebiscite to unite his team, to unseat UKIP and to cement Britain within the EU. A catastrophic miscalculation on all three counts.

Still, the best laid schemes and all that sort of thing. As an Ayrshire woman, Ms Sturgeon undoubtedly knows the next Burnsian verse. She may envisage David Cameron bemoaning "thou art blest compar'd wi' me".

But they both might usefully conclude: "An' forward, tho' I canna see, I guess and fear."