Could the Scottish Parliament stop the UK from leaving the EU?

- Published

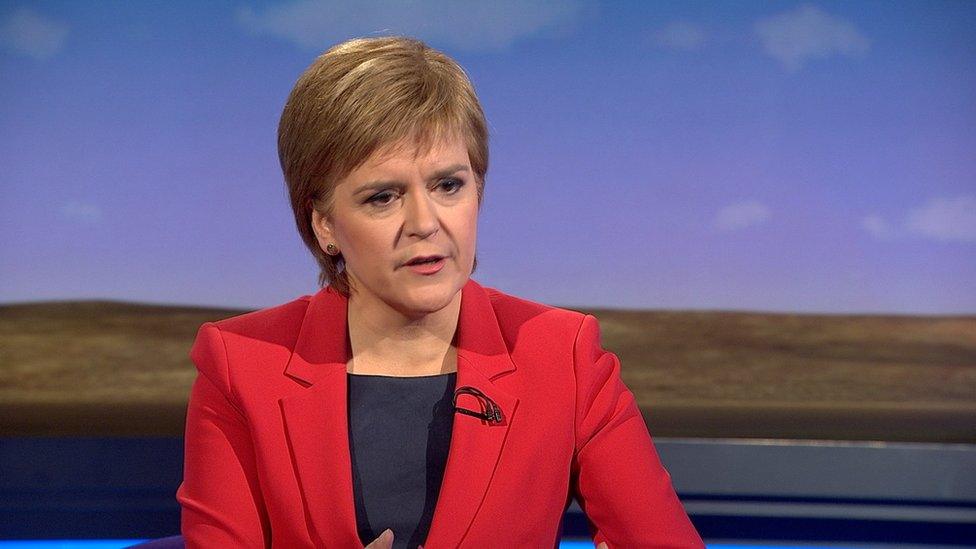

Nicola Sturgeon: Scotland could veto Brexit

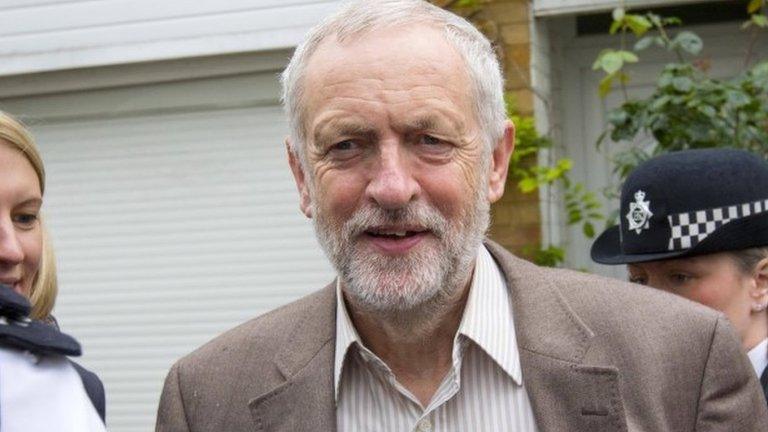

To recap. The Prime Minister has resigned. The leader of the opposition is resisting pressure from senior colleagues to follow suit.

And, lest we forget in this temporary focus upon party leadership, the people of the United Kingdom have voted to leave the European Union after 43 years of membership.

In these unprecedented circumstances, it is understandable that there is a degree of uncertainty in the immediate response to events.

That disquiet includes Scotland where the First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, is seeking to draft a distinct reaction within the distinctive Scottish body politic.

She has said that the people of Scotland have voted, clearly, to continue in membership of the European Union, with its attendant rights and responsibilities. It is her duty, she argues, to attempt to carry out that popular instruction.

First things first. Is there such a mandate? Ms Sturgeon says yes. She says Scotland is a nation - although not presently a state. She is the elected political leader of that nation, constrained by that office to follow the wishes of her voters.

How would you expect her, as a Nationalist, to say anything else?

It is the fundamental creed of her cause that Scotland is distinct and merits distinctive treatment, within the limits of shared sovereignty and co-operation which characterise the modern SNP.

Others of a Unionist persuasion say no. The Scottish Secretary, David Mundell, for example says that Scotland remained within the Union via the referendum of September 2014 - and that Scotland, consequently, is bound by UK collective decisions such as the vote on Thursday.

Nigel Farage and David Coburn of UKIP put it more bluntly, in their customary fashion. They dismiss utterly Ms Sturgeon's elemental pitch.

What can Nicola Sturgeon do?

It was notable, however, that David Cameron stressed the involvement of the Scottish government and other devolved administrations in the EU negotiations to come.

Boris Johnson, he who agitated for Leave, seemed almost plaintive when he said there was no reason why Brexit should cause any disturbance in the domestic Union.

These, however, are differences of tone. Although such things matter, no Unionist will readily accept that Scotland should do anything other than submit to the declared will of the UK, as expressed in the vote on Thursday. That is, unless and until Scotland is an independent state.

So what can Nicola Sturgeon do? She has said she will examine all options in consort with the European institutions and others to seek to secure continuing links with the EU for Scotland.

One of those options would be a second independence referendum - in order to allow Scotland to join/rejoin the EU in her own right, as a sovereign state.

But what about those other options? In particular, what about the suggestion that Ms Sturgeon might encourage the Scottish Parliament to seek to exercise a veto over the implementation of Brexit?

Does it mean Holyrood has a veto over Brexit?

This scenario is based upon an interpretation of the Scotland Act 1998, external, the statute which created (or, rather, recreated) the Scottish Parliament.

Clause 29 of that Act, anent legislative competence, empowers the Scottish Parliament to legislate in the devolved areas for which it is responsible - while obliging it to take care that nothing it does is "incompatible" with EU law.

In short, EU law has force in Scotland and, in devolved areas, is enacted and implemented by the Scottish Parliament, not Westminster.

MSPs return to Holyrood next week where Brexit

That has led constitutional experts, such as Sir David Edward to suggest that the consent of the Scottish Parliament would be required were it to be suggested that the UK's relationship with the EU, in legislation and other areas, might be altered.

Sir David made this point in evidence to a House of Lords inquiry, external. Their Lordships report cited Sir David as envisaging that there might be "certain political advantages" to be drawn from withholding consent.

Which is true. It is further true that it is an established Convention (formerly known as the Sewel Convention) that the Westminster Parliament should not interfere in devolved areas without the consent of Holyrood. Such agreement is customarily given via a legislative consent motion, LCM, at Holyrood.

So does that mean Holyrood has a veto over Brexit? Up to a point, Lord Copper. Firstly, one should understand that relations with the EU have a long and complex history, in the context of the demands for self-government.

What does the law say?

A seat at the EU top table has long been a prize sought after by supporters of independence. Even those who backed devolution, rather than full independence, foresaw that Scotland would develop her own relations with the EU, in consort with the UK.

Thus the White Paper of 1997 which led to the 1998 Act fudged the issue, external. It said that dealing with the EU was a matter for Westminster, alongside foreign affairs.

But it suggested that the UK government would seek to consult the devolved administration in Scotland and take account of its views.

Let us turn now to statute. The 1998 Act proceeds by specifying the issues which are reserved to Westminster - then grandly declaring that everything else is devolved.

Schedule V to that Act lists the reserved areas. At sub-clause 7, it is noted that "international relations, including relations with territories outside the United Kingdom, the European Union and other international organisations" etc….."are reserved matters." They are, in short, Westminster's purlieu.

However, it then goes on to note that this reservation does not include obligations under EU law.

Hence, Nicola Sturgeon's argument that Holyrood is entitled to a say: based upon the legal formula which obliges Scotland to adhere to EU law. Westminster might usefully point to the broader Schedule V, reserving relations with the EU to the UK.

Then there is a further point. Clause 28 of the 1998 Act notes at sub-clause 7, in dry terms, with regard to legislative competence that "this section does not affect the power of the Parliament of the United Kingdom to make laws for Scotland."

In that single little line is the subordinate nature of devolution. Generally, Westminster will let the Scottish Parliament get on with devolved legislation. Carry on governing. But it is also made clear that Westminster's ultimate sovereignty over the UK, the entire UK, is unaffected.

So it could be argued - it is already being argued - that, if it came to a constitutional battle, Westminster would have the final say. Holyrood might withhold consent for the legislative moves to implement Brexit.

Mr Cameron has announced he will step down by October

Westminster might note such a verdict, no doubt with polite gratitude - then proceed to implement Brexit, exercising its over-riding sovereignty.

Would that be wise? Would it be politically smart? Those are different questions, to discuss should this issue arise for real.

To be clear, Nicola Sturgeon is not personally making a big deal of this. She is not issuing scatter-gun threats.

She is attempting to remain calm, adopting the persona of one of the few serving leaders in these islands not resigning or under pressure to resign.

To be clear, further, she did not float the issue of a "veto" on Friday in her formal response. It emerged today in reply to decidedly adept questioning from my estimable colleague, Gordon Brewer.

Where does this leave an Indyref2?

Just as with the tone adopted by David Cameron and Boris Johnson, I think Ms Sturgeons' demeanour is significant.

She is seeking to make slow, steady progress. In particular, she is not anxious to drive forward to an instant referendum on independence.

Why not? Because she fears she might lose it. The big challenges she faced in September 2014 were: the economy, the currency and membership of the EU. The third factor has now altered somewhat, positing the prospect of indyref2.

However, items one and two remain. What would independence do to the economy? What currency would an independent Scotland use?

Further, still, it is possible that Brexit might encourage furious Scots - and many are decidedly angry - to move in greater numbers towards independence.

Equally, it might make some think that the constitutional world is already scary and uncertain enough without revisiting the prospect of independence at this stage.

Ms Sturgeon, as she has made amply plain, wants more evidence that the people of Scotland are ready this time round to back independence. So she wants time. She needs time.

Hence, partly, the search for alternatives. The search for any means by which Scotland can maintain EU links.

To be clear again, this is a genuine, governmental search. Ms Sturgeon is not bluffing or deploying guile. She, authentically, wants ideas as to how to proceed.

Could Scotland stay in the EU?

Equally, however, she acknowledges that it may well be the case that there is nothing short of member state status which replicates, for Scotland, the EU links currently provided via the UK.

She has not specified options - but let us speculate. What might be possible? Could Scotland gain a distinctive status as, in reverse, is the case with Greenland and the Faroes which are parts of the Kingdom of Denmark, yet not in membership of the EU?

Well, maybe, although Scotland is decidedly different. The Scottish government are seeking to retain membership, once the member state of which they are part has left. Secondly, Scotland is an intrinsic part of the UK economy and the UK's treaty obligations.

It might be thought difficult to disentangle Scotland's rights and obligations from the wider UK.

It is possible to envisage a situation where distinctive status within Brexit is afforded to, say, Gibraltar. Scotland may be trickier.

All 32 council areas in Scotland voted to Remain in the EU

However, as one senior member of the UK Government said to me, Europe is all about the politics. The constitutionally impossible suddenly becomes feasible if the EU's leaders want it and need it.

But would they? Politically, would they? It seems probable that the old objections would arise. That member states like Spain and Belgium would not want to encourage special status for Scotland which might, in very different circumstances, be demanded by their own autonomous provinces.

Then what about associate membership status for Scotland, which has been floated? It is not clear what that would mean. How, for example, could rights and responsibility be accorded to Scotland without drafting new treaties which applied to Scotland alone? How would that fit with the removal of treaties affecting the UK?

How could Scotland, for example, access the single market and retain freedom of movement for workers while remaining part of a political entity, the UK, which has withdrawn from those elements?

I do not know. And, more importantly, Nicola Sturgeon does not know either, at this stage. To repeat, she is genuinely seeking answers. But, tactically, she is also buying time if it becomes evident that the only route to be pursued is that of independence via a second referendum.

And now, the epilogue. Today Dr Russell Barr, the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, has issued a prayer, to be used, if they so choose, by the Kirk's 800 Ministers. It concludes by seeking intercession to "free us from all bitterness and recrimination".

Amen to that.

- Published26 June 2016

- Published19 June 2016

- Published27 June 2016