Battle of the Somme: Carnage for the Scots battalions

- Published

British soldiers with bayonets fixed advance into No Man's Land at the Battle of the Somme

At Zero Hour on 1 July 1916, five battalions recruited in Scotland went over the top on the Somme.

As the day progressed they would be followed by others thrown into the battle plan of their fellow Scot, Gen Douglas Haig.

Haig had masterminded one of the biggest artillery attacks the world had ever seen or heard; an incredible seven-day bombardment of one and a half million shells fired by 50,000 gunners.

They were confident they had destroyed the enemy's deep dug-outs and defensive systems and cut the barbed wire in No Man's Land, thus allowing even the most inexperienced volunteer soldiers to storm not just the German front line, but the second and the third line too.

Wire not cut

But the bombardment was not concentrated enough and too many shells were poor quality and failed to explode. The barbed wire was not cut. The Germans were not all dead. Their big guns were not all out of action.

Their machine gunners might have been demoralised by tons of high explosives falling on their bunkers, but soon they were galvanised by the opportunity to hit back. And hit back they did.

Of the five battalions moving off, four of them were made up of friends and workmates recruited from their local area: from Edinburgh the 15th and 16th Royal Scots - the latter the famous McCrae's battalion, noted for its football connections; while from Glasgow came the 16th Highland Light Infantry (the Boys' Brigade battalion) and the 17th City of Glasgow.

British commander on the Somme General Haig greets his French army equivalent Joseph Joffre

All would suffer heavy casualties, but probably the worst affected was the 16th HLI. Most of them didn't even make it to the uncut wire, let alone the enemy trenches beyond. They were cut down in their masses by machine guns and artillery.

British soldiers rest in a communication trench prior to going to the front

Within 10 minutes they had lost half their strength. Those who made it to the wire and got caught there, could be slaughtered at the enemy's leisure. And it achieved nothing.

Soon others were joining the fray. The Kings Own Scottish Borderers went in next in the attack on the village of Beaumont Hamel. They too were mown down without taking an inch of enemy trench.

Minor gains

Those who had got across: the Royal Scots, the 17th HLI, the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, now fought grimly in their hard-won bites of German redoubts.

By 09:30 the 2nd Seaforths were in action doing the same. By 10:00, there was one small ray of good news: the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers in the south with the Manchesters, took their objective: Montauban. Their losses were light.

Much later in the day the 2nd Gordons too would take their target: the fortified village of Mametz, but for a heavier price.

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916 and was fought along a 15-mile front near the River Somme in northern France

19,240 British soldiers died on the first day - the bloodiest day in the history of the British army

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day

At the end of hostilities, five months later, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence

In total, there were over a million dead and wounded on all sides, including 420,000 British, about 200,000 from France and an estimated 465,000 from Germany

Find out more:

It's not true that all these men who went over the top walked into a hail of machine gun fire, nor that all the attacks failed. Commanders tried a variety of tactics and in the south there were real advances.

The Scottish battalions, like everyone else, suffered a mix of fates and there were plenty of Scots and even entire battalions identifying as Scottish, such as the Tyneside Scottish and London Scottish, spread through the rest of the attack. But over the day, the gains were small, the losses great.

Where the attacks had failed utterly, a new tragedy was unfolding. Wounded and dying men were trapped in shell holes under a blazingly hot, clear, July sky. They had no water or medical aid. If they moved, the German snipers shot them.

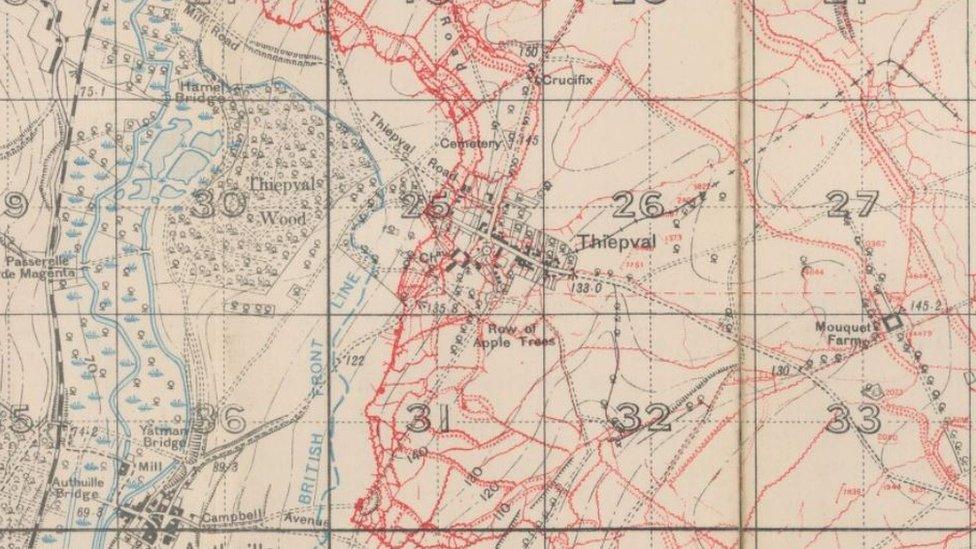

A British map of part of the front line showing the two opposing sets of trenches

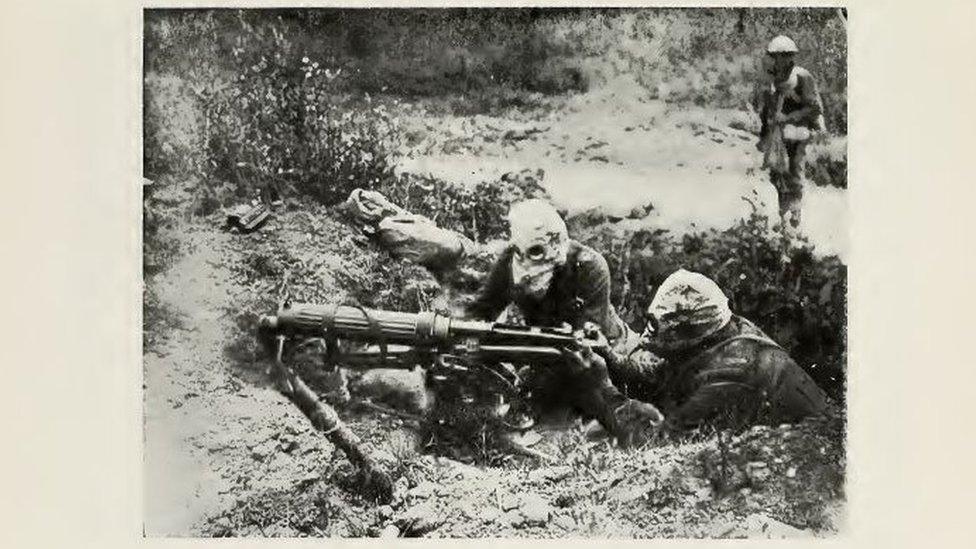

For some of the uninjured men trapped alongside them, doing nothing was more than they could bear. One soldier of the nearly obliterated 16th HLI, L/Sgt John Anderson decided to fight back. He had a machine gun and the ammunition of his slain comrades.

His commanding officer recounted how, "observing a break in the enemy trenches, the sergeant trained his gun on the opening. As there was considerable traffic along the trench he caused great execution.

"Having exhausted 24 drums of ammunition and being the last of the section left, he crawled back at dusk to the line, bringing his gun with him."

On 1 July 1916, dusk was a long way away for a man who had started at 07:30.

John Anderson was awarded not only the DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) but the more exotic Russian Order of St George 3rd class.

John was a 23-year-old engineer from a calico printing works in Campsie, Stirlingshire. The local paper called him "Our DCM" and avidly followed news of his deeds.

Sadly in October that year, just as the parish council was planning a public meeting to welcome home their local hero, he was killed. His leave papers had already arrived, yet he volunteered for a bombing raid into the German trenches. He never came back.

British machine gunners wearing gas masks in action later in the Battle of the Somme

A year later, his grieving father received a box of his effects from the German government containing a soldier's hymn book, letters and photographs.

By this time, John's elder brother had also been killed, leaving a widow behind him. John was one of the "lucky" few survivors of the 16th HLI on the Somme, but there was no happy ending.

For so many homes the story was less acclaimed, but the grief was the same.

- Published28 November 2014