How Newfoundland soldiers forged lasting link with Scotland

- Published

Newfoundland soldier James Cooper returned to Scotland after WW1 and married Ayrshire woman Margaret

Soldiers from Newfoundland made quite an impression when they took up garrison at Edinburgh Castle in 1915 but just over a year later they were virtually wiped out on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Despite the tragedy the regiment has a lasting link to Scotland.

World War One saw soldiers from across the British Empire volunteer to defend the "mother country".

Foremost among them were men from Newfoundland, then not yet part of Canada, who took the city by storm when they arrived in Edinburgh in 1915.

They went on to form a lasting relationship with Scotland, with some choosing to stay once the fighting was over.

In February of 1915, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment became the first non-Scottish troops ever to garrison the city's famous castle.

They went on to fight at Gallipoli and then tragically were cut down in their hundreds at the Battle of the Somme.

At the time, Newfoundland was a small dominion with its own prime minister, moving towards independence within the British Empire.

Its soldiers were known as the "Blue Puttees" for the colourful leg wrappings they wore instead of standard-issue khaki, and Edinburgh welcomed them.

Parades, speeches and sports events marked their visit.

They didn't do too well at rugby, which many of them had never played before, but they cut a dash at Edinburgh's fancy new skating rink where flying hockey pucks endangered both spectators and posh statues. That was more like it.

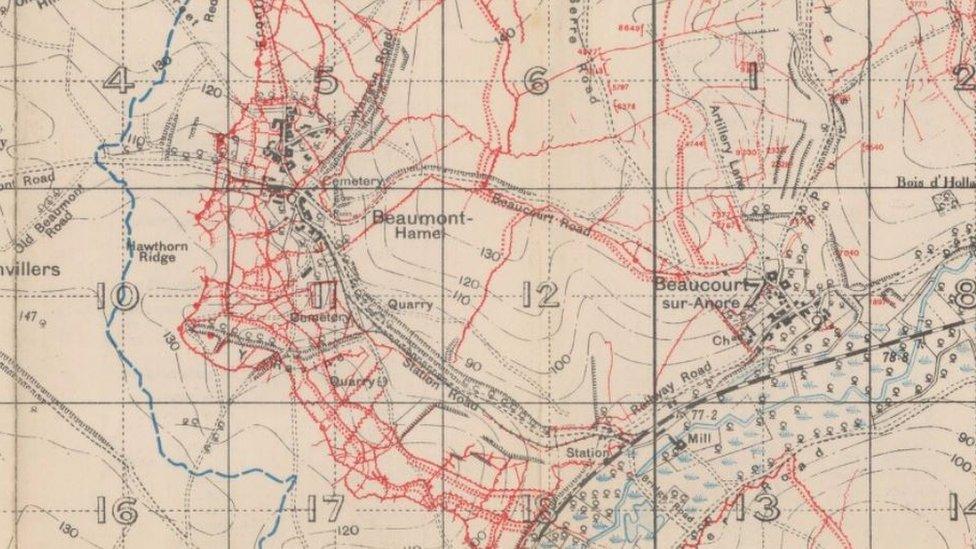

A statue of a caribou - the Newfoundland regiment's emblem - is unveiled at Beaumont-Hamel in 1925

Confined to barracks the night before leaving, they even staged a great escape to Princes Street, scaling the castle walls with ropes and knotted sheets in search of fun. No heavily guarded gate could keep them in.

But it was in Ayr that the Newfoundlanders made their most lasting Scottish ties. It became the site of the regiment's reserve depot and started a friendship that still continues.

The provost of Ayr noted that the population of Ayrshire and the population of Newfoundland were about the same and gifts were exchanged including a lavish, silver cigar casket with the burgh arms.

A few months later, a handsome caribou head, the emblem of the regiment, was presented to the people of Ayr by the Prime Minister of Newfoundland, in gratitude for their hospitality to his soldiers.

The Caribou head given by the Prime Minister of Newfoundland is part of South Ayrshire Council’s Museum collections

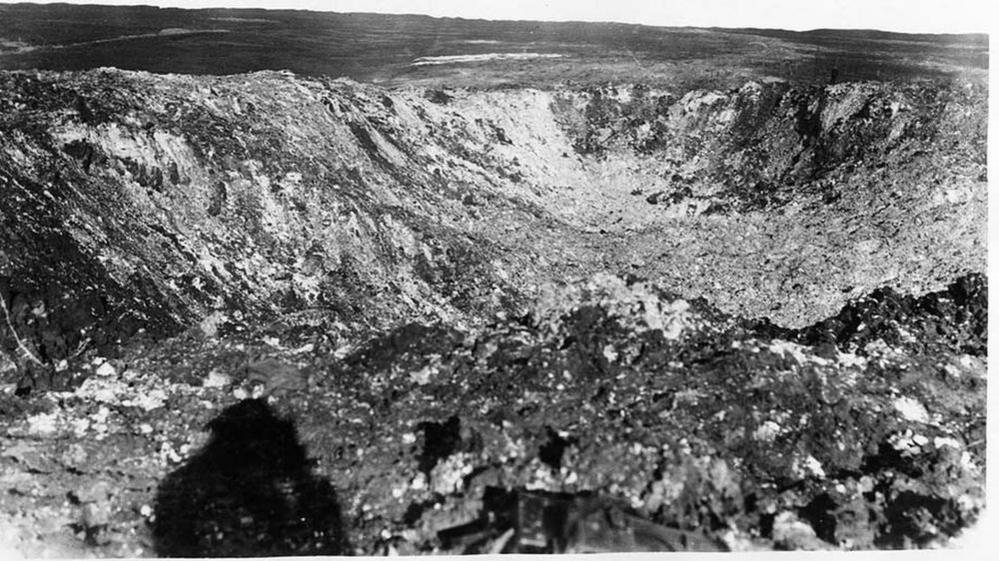

This crater was left after British engineers exploded a huge mine under German positions near Beaumont-Hamel

The caribou is still in Scotland today, part of South Ayrshire Council's museum collections.

But anyone who has visited the battlefields of the Somme knows another caribou, the statue in the Newfoundland Memorial Park that marks 1 July 1916.

On that day their tiny force, just 800 strong, went forward at Beaumont-Hamel on the Somme.

They went alone. They had no artillery support. The regiment supposed to be strengthening their flank wasn't there.

A killing ground lay in front of their lonely advance but no order came to stop and so, they went.

A witness from a Scottish regiment could only watch in horror. Pte FH Cameron of the King's Own Scottish Borderers said: "On came the Newfoundlanders, a great body of men, but the fire intensified and they were wiped out in front of my eyes.

"I cursed the generals for their useless slaughter - they seemed to have no idea what was going on."

Eight hundred members of the Newfoundland Regiment went into battle at Beaumont-Hamel. The next day, at roll call, of those 800 men just 68 answered.

The Battle of the Somme

Began on 1 July 1916 and was fought along a 15-mile front near the River Somme in northern France

19,240 British soldiers died on the first day - the bloodiest day in the history of the British army

The British captured just three square miles of territory on the first day

At the end of hostilities, five months later, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence

In total, there were over a million dead and wounded on all sides, including 420,000 British, about 200,000 from France and an estimated 465,000 from Germany

Find out more:

One of the survivors, James Cooper, regiment number 98, was too badly wounded to go back to active service, so he returned to Ayr where he left a lasting legacy - a family.

His great-grandson, film-maker Iaian Cooper Sands, keeps his memory and Ayr's Newfoundland connection alive today through his blog and museum events about his family story.

'Horrific dreams'

Iaian tells how his great-grandfather spent the rest of the war as a Lewis gun instructor, marrying his Scottish great-grandmother, Margaret, who confessed that she couldn't resist his "smart appearance due to his blue puttee uniform and swagger stick".

It was hard for them after the war. James had to return to Newfoundland and raise money to come back to Scotland, but they were finally able to raise their family together in Ayr.

According to Iaian, his great-grandfather felt the impact of the war for the rest of his life, suffering "horrific dreams, night sweats and moments of withdrawing into himself".

They were problems that many other Newfoundland veterans suffered, and they were the fortunate ones. One in five of the men who sailed for King and empire to help the "mother country" never came back.

A map shows the two front lines in the Beaumont-Hamel area where the Newfoundlanders fought

The strain of the war on Newfoundland's tiny economy, which relied on cod-fishing, was hard to bear.

Even the war pensions for the bereaved and wounded made a major dent in the public finances and left no room for manoeuvre.

In 1932, the world-wide slump hit hard and the government said it had to cut those pensions by as much as 30%. There was a riot.

The riot was a milestone on Newfoundland's path away from full independence within empire.

Although many factors influenced its choice to join Canada, it's likely that the crippling expenditure and heavy sacrifices of World War One were a major underlying cause.