A glacial gold rush in the glens

- Published

It weighs ten ounces, it's a pockmarked, dirty, greyish yellow. But to jeweller Sheila Fleet, it's a nugget of history.

The first pour from the first commercial goldmine in Scotland, in a chunk known as a doré, contains at least eight ounces of pure gold.

It's part of the hundred ounces (3.1 kg) that will go to the Edinburgh Assay Office, which is legally empowered to verify its provenance and ensure that the journey to the consumer is protected.

Scott Walter, chief executive of the Assay Office, was on hand at the official opening of the Cononish mine - five miles up a mountain track from the central Highlands village of Tyndrum. His rough estimate, reluctantly given, is that Scottish gold might command a premium of 10 to 15% over the world price of gold.

Orcadian designer Sheila Fleet didn't disagree. She has an eye on part of that haul, along with more plentiful silver, to get it into her Christmas collection and the wedding range planned for next year - even if it is a small part of the alloy.

Performing the official opening, Bruce Crawford, local MSP for the mine on the edge of Stirling Council area, was enthusiastic about getting a replacement wedding ring made from Scottish gold. So yes, there's a market there.

But it's likely that most of the output from Cononish will be exported for specialist smelting and would lose that provenance in the process. Richard Gray, the chief executive of Scotgold Resources, operator of the mine, would like smelting eventually to take place within Scotland, perhaps at Grangemouth.

If the premium is right, that could maintain the provenance. But smelting gold is a toxic chemical process, and not one to be performed on a remote Scottish hillside.

Rocky road

Nearly three decades after work began on sinking a horizontal shaft into the mountainside, these still feel like early days in a precarious adventure.

There have been numerous bumps and delays along the rocky road to the first pour of gold. Some have been from the planning process.

The mine project coincided with the creation of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, and it has taken a long time for the two ventures to see eye to eye on environmental and visual impact. They claim to do so now.

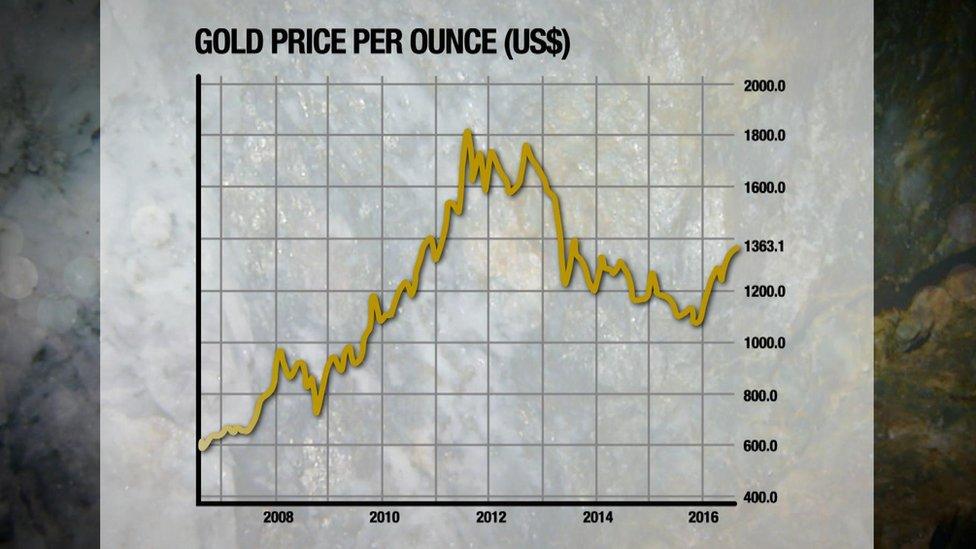

The gold price has been highly volatile. Ten years ago, it was at $600 per Troy ounce (31 grams). There was a rush to gold as an investor's safe haven when the Eurozone crisis peaked, peaking close to $1800.

The world price then plummeted to below $1100. And with the recent uncertainty from China's slowdown and Britain's Brexit, it is back in the $1350 range.

That volatility makes it harder to secure funding, from all but the most battle-scarred investors in mineral mining.

A change atop Scotgold Resources over the past two years led to an exit from a complex and expensive bank overdraft. That was led by the new chairman, Nat le Roux.

Investment solution

Toasting the opening with fellow investors and local community worthies, he recounted the difficulty of finding another lender. The problem was not one of high interest rates, he explained, but of onerous covenants and high fees.

Investment funds with a specialism in minerals were not interested in a project as small as Cononish. These fund managers think in multiples of $100m.

So a sort of solution has been patched together, of being patient and incremental. A modestly-sized processing line has been imported from a South African equipment specialist.

Starting in May, 300 tonnes of ore have been crushed. They're upping from one to two shifts. This year will see 2400 tonnes crushed, battered, spun, shoogled on a mechanical panning table, and the precious dust baked at 1200 degrees.

If the experts have judged the geology correctly, that would produce up to 15 kilograms of gold this year. With the first eight ounces of that (250 grams), the message from the opening ceremony was to investors, to say that there's progress now under way, albeit slowly.

The column inches gained from this week's ceremonial cutting will be of value when the next funding round gets started.

The bigger picture is to mine around 550,000 tonnes, extracted from a series of galleries cut into the vertical quartz rock seam. That would require an increase in staffing from seven, at present, to 60.

Independent analysis suggests that should include a recoverable 200,000 ounces of gold, and a reserve of perhaps 250,000 ounces. That's at least six tonnes of pure gold, which at current dollar market value - helped by the weakening of sterling - would fetch more than £200m.

That's not all. Far from it. Chris Sangster, a mining veteran who has stuck doggedly with the Cononish project for 20 years, says Scotland has a potential for mineral extraction which has been neglected by investors.

Quartz seams

He points to a geological feature that runs from Northern Ireland through Argyll and into Perthshire, which ought to include further gold bearing seams of quartz.

So Scotgold Resources has secured a six-year licence from the Crown Estate to survey and test drill across an area of 4,100 square kilometres - from the Argyll coast near Crinan and Lochgilphead, skirting round Inveraray, and stretching north-eastwards to Pitlochry. A further licence area is in the Ochil hills north of Stirling.

The next best prospect after Cononish looks like Glen Orchy, to the north of Tyndrum. Sangster says the chances are that there are no supermines to be found. This is not extraction on a South African or Australian scale. It is more likely to be on the scale of Cononish.

That means this nascent industry would remain vulnerable to the volatility of the gold price, and to the challenges of finding finance.

This long process to get to 'first pour' might be reduced by lessons learned and confidence gained from the Cononish experience. But as gold rushes go, this one appears to go at a relaxed pace.

- Published3 August 2016