In for a penny, not for the pound

- Published

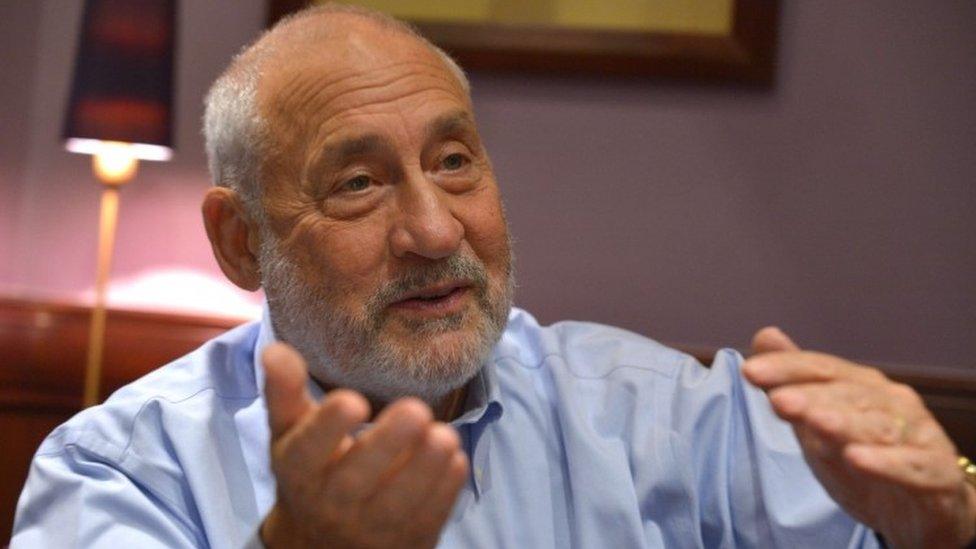

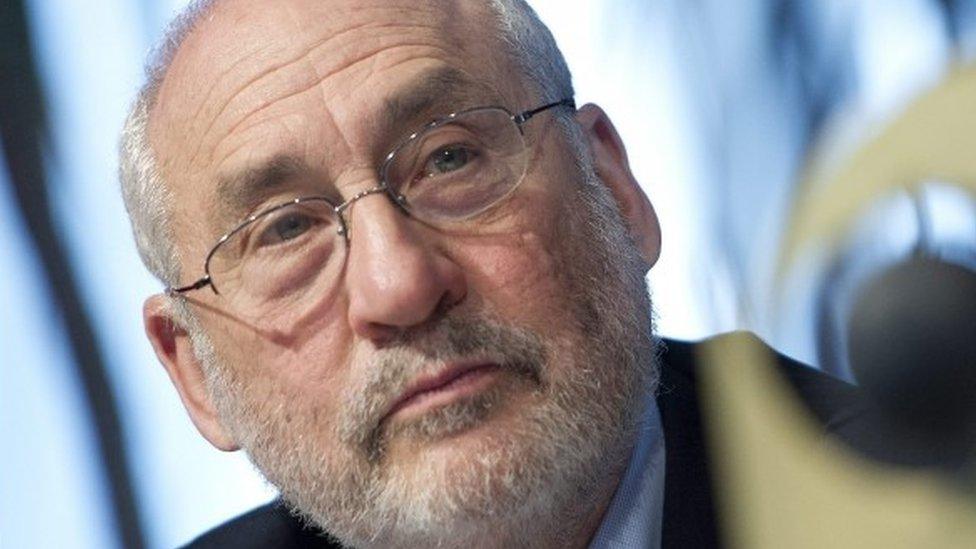

Joseph Stiglitz is one of two Nobel laureates on the Council of Economic Advisers to the Scottish government. Their status was often cited by the Scottish government in 2014 to back the economic case for independence and for a continued currency union with the rest of the UK.

That currency plan was the most intense pressure point from the Better Together campaign.

It is now acknowledged by independence campaigners that it should be re-thought. Even if it was the right policy, it left the campaign exposed.

It was asserted that the UK would have to agree to a currency union, on three hotly contested grounds - with the assertion that sterling was "an asset" belonging to all of the UK, it was seen as being in the UK's economic interests, and because Scotland could refuse to take on a share of UK debt if it did not.

The main Westminster parties stated they would not do such a deal. And they pushed the SNP's independence campaigners to state what their "Plan B" would be.

Now Prof Stiglitz has told BBC Scotland the currency proposal "may have been a mistake" - not on presentational grounds, but on economic ones.

Flow of funds

This is consistent with his critique, in a new book, of the euro currency project. He believes it is flawed through a lack of political integration to back up the economic links, and because Germany has enforced fiscal discipline too severely.

By contrast, he points out that the USA dollar-zone relies on flows of funds from strong parts to weak. Federal funds can help bail out one part of the country at a time of crisis.

Imbalances in America can also be reduced by the flow of people from areas of high unemployment to areas where there are job opportunities. But as Britain's EU vote demonstrates, that has become increasingly contentious.

Prof Stiglitz says the currency proposal "may have been a mistake"

The suggestion put forward by Prof Stiglitz, and being discussed by independence campaigners, is for an independent Scotland to have its own currency.

This could float against others, which would let it absorb economic divergence. It could be a condition for entry to the EU - though the professor advises against then joining the euro.

It would not be cost-free, however, as currency exchange brings costs of transactions and of the risk of volatility.

Setting up a new currency would require a central bank with the backing of currency reserves.

It would need to win the confidence of international markets, which could require signalling a strengthening of fiscal discipline.

And before that, it would have to win the confidence of the Scottish public. You may recall the question of whether voters wanted their earnings, savings, pensions and loans to be re-denominated in a new currency.

If the sharing of sterling "may have been a mistake", the alternatives are not easy either.

Dilemma upon dilemma

The re-opening of the debate about the currency used by an independent Scotland brings up quite a lot of complexity. Now that the Scottish government's priority is to ensure continued access to the European single market, it hasn't got any easier. Here's why:

* A new member of the European Union has to promise to prepare for membership of the euro currency. Only the UK and Denmark have permission not to do so. Sweden is showing no signs of wanting to join, though it is technically obliged to prepare to do so. Some others, such as Poland, are not thought to be in a rush either.

* To prepare, a new member has to have control of its own currency, with monetary institutions including a central bank. This should be for at least two years, and is to let the new EU member demonstrate its reliability in managing monetary affairs.

* Preparation for membership requires the government deficit to be no more than 3% of Gross Domestic Product, or total output, and government debt below 60%. Last year, official statistics point to a 9.5% deficit on all government spending and taxation in Scotland. UK government debt is around 80% of GDP, and may be about to go higher. An independent Scotland's share of that would have to be negotiated.

* There is a case for a country pegging its currency to its main trading partner. For Scotland, by a wide margin, the biggest customer for goods and services is the rest of the UK. For that reason at least, it would make sense to be part of the sterling area (which was the SNP case made in 2014), or committed to maintaining a stable exchange rate between sterling and a Scottish currency.

So here's the dilemma for an independent Scotland: stick with, or close to, sterling because that's what the main trading partner uses, at the same time as telling the rest of the Europe that Scotland intends to fulfil the EU membership commitment to join the euro.

At the same time, set up a new currency, with no intention of floating it, and perhaps for only two years, while bringing the deficit down from nearly £15bn to less than £5bn.

Two alternatives: one is return to the 2014 white paper and the tactic of saying that Westminster would have to do a deal with Scotland on joint control of sterling, whether through self-interest or once threatened with Scots refusing to take on a share of UK debt.

Or Scottish government ministers could go to Brussels and around 27 other capitals and explain that Scotland is a special case. It's been inside the EU for 43 years, and ministers argue that it is being taken out of the European Union against its will. Therefore, the case goes, these rules should be put aside, or Scotland should be treated as the successor state to the United Kingdom, and should inherit its eurozone get-out clause.

- Published30 August 2016