Herding Scotland's sheep back into the profitable pen

- Published

Here's a job with a difference - an ambassador for Scotland's sheep.

This agri-addition to the diplomatic corps must wear wool. Enthusiasm for mutton pies is required. French language skills an advantage. And don't get too sentimental about the poor wee lambs.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to reverse the downward trend in mutton and lamb consumption in Scotland. To ram the message home, you must be more bullish than sheepish.

This is just one of 24 recommendations of an independent study of the sheep farming sector, external.

It concluded that the industry could get a £26m annual boost if it gets the average margin on sheep rearing up to the performance of the industry's best third.

It could also increase the industry's output with a target of persuading Scots to raise consumption per head by 1kg of sheepmeat per year. Recently, it has been 2.5kg to 3kg. That would mean 20% more 'kills', or 250,000 more carcasses. (I warned you not to get squeamish.)

Scottish consumption is just over half of the UK's 5kg average, and a third of Australia's. The UK, meanwhile, has Europe's biggest demand for mutton and lamb.

Britain is the third biggest exporter of sheep meat, after Australia and New Zealand. Yet it is the third biggest importer, after China and France.

The Scottish Sheep Sector Review was set up at the invitation of the Scottish government, and chaired by a former sheep farmer of the year, John Scott, whose farm is near Tain in Easter Ross. The group comprised 13 such figures from the industry.

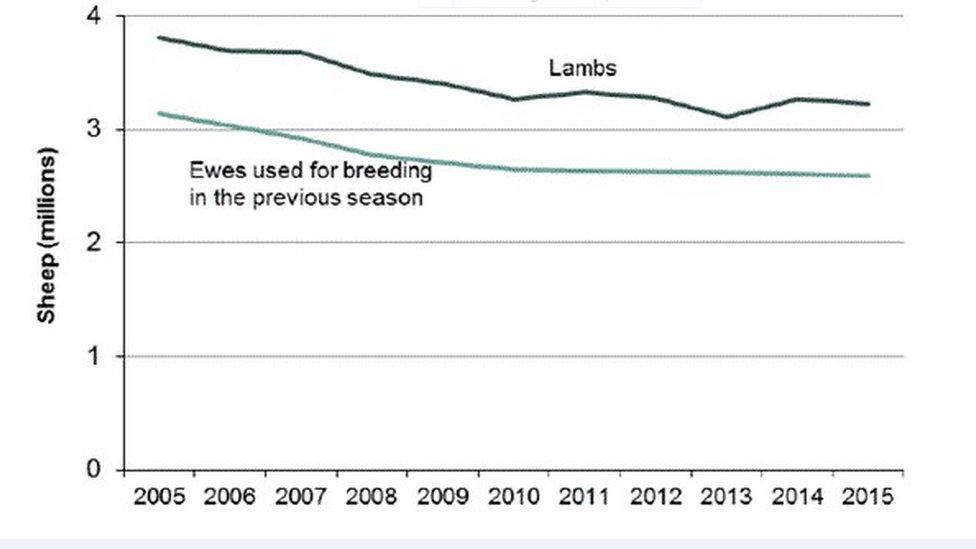

Its final report reflected a decline in sheep farming since subsidy changes were introduced in 2005.

Last year's farm census (in June, though with all that slaughter, numbers can change rapidly) showed 6.7 million sheep in Scotland, on 14,900 farms and crofts.

A study from the Scottish Agricultural College, published five years ago, noted how that had fallen steeply since 1998, when the census hit 10 million sheep. Farmers were found to have responded to market and subsidy signals, with the sharpest falls in Lochaber and the Western Isles, while the Borders grew in its share of the sector.

It noted that sheep were not the destructive munchers of landscape that they might appear to be. A study around Lairg in Sutherland found that deer numbers increased, as did rank vegetation.

There were fewer farmland birds, fewer rabbits and hares, less species diversity including raptors, crows and, as you might expect, foxes. There was an increase in tick-borne disease - though it wasn't explained why. And as sheep farmers reduced their costs by cutting back on farm employment, there were fewer people to work on improvements with environmental benefits.

Since 2010, the numbers seem to have stabilised. But this week's report claims that the profitability level rarely justifies the unpaid time and risk capital required. The gross margin per ewe for upland farms is £60 on average, and £81 for the top third of production. Margins for hill farming average less than half as much.

The most recent figures from Quality Meat Scotland show 27,500 tonnes of sheep meat produced in Scotland each year, of which 14,000 to 15,000 tonnes are consumed in Scotland.

Half the slaughters of Scottish-raised sheep take place outside Scotland. Of those put through Scotland's 19 licensed abattoirs, more than quarter are exported from the UK.

The report set out to find ways to boost profitability, increase throughput and add value. It recommended better training and sharing of experience between farmers, with modern apprenticeships for sheep farming.

It called for broadband and mobile coverage across all of Scotland. That means instant access to market information, but it may be more significant that it makes the sector attractive to new entrants from the digital native generation, for whom ram can also be computerised.

There were recommendations for research into genetic selection of breeding stock, and into market demand.

There was a call for co-ordination of the supply chain to improve the matching of supply with market demand throughout the year.

The call for a campaign to boost consumption of sheep meat runs counter to health messages about reducing red meat eating.

And while there has been a decline in conventional ways of buying prime cuts and cooking them at home, that has been partially offset by the use of sheep meat in pre-cooked meals and when eating out.

'Worldwide reputation'

According to John Scott: "We have a worldwide reputation for the quality of our beef. Our hidden secret is our lamb, which also has a fabulous story to tell in terms of product provenance and availability throughout the year - from lowland spring lamb on through upland lamb in the autumn to high hill lamb in the winter. We need to become greater advocates for the products we produce.

"Not only do we need to work on understanding and improving the efficiency with which we produce meat and wool - we also need to understand better the qualities of the meat we produce and how consumers can use our products. We can become ambassadors for what we do and what we produce."

So where do ewe sign up to be ambaaaasador? (Yes, brace yourself for a job with a lot of bad puns.)