Sturgeon gets down to business

- Published

It used to be known as Holyrood's Queen Speech. But there's no gilded carriage, horses or flummery on Programme for Government day.

Instead of regal bling and ermine, the star of this show rocks up in Totty Rocks togs. There's no pomp, but there is quite a lot of circumstance.

And the circumstances in question are political, economic and constitutional.

The political: this was the Holyrood remix of the SNP manifesto from last spring. After a summer in the hands of ministers and civil servants, this was not merely a list of 14 government bills: this was a programme for four-and-a-half years, and therefore quite a meaty document.

Then the constitutional: the fifth Scottish Parliament, from 2016 to 2021, is at risk of being knocked off course by the decision taken seven weeks after the election for the UK to exit the European Union.

That has raised expectations of another independence referendum. But between the start of the 'national conversation' last week, and a consultation on a draft bill announced in the Programme for Government, it looks a bit like Nicola Sturgeon is asking questions to which the answers will require her more gung-ho followers to ca' canny and show some patience.

The scope of the Programme for Government also poses a challenge to those who say Holyrood lacks sufficient powers. There's a lot in it, deploying many of the powers it's got.

And the economic: Scotland had already moved into an unhappy position relative to the rest of the UK. That has seemed mostly to stem from the oil and gas downturn, spreading across the country.

Ms Sturgeon's opponents suggest it might also have something to do with a chill on investment that comes from neverendum. It's hard to prove if that's the case or not.

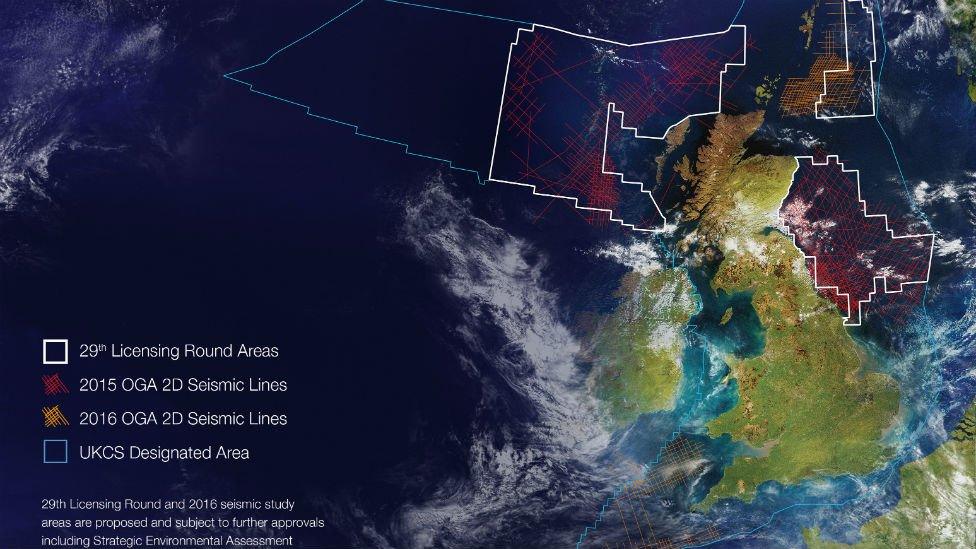

A strategy for decommissioning aims to ensure the offshore industry continues to benefit Scotland

The range of action taken on the economy provides a range of defences against the charge that Nicola Sturgeon is either too concerned with independence to care about other matters, or that she is too concerned with public services and social justice to understand what the economy needs.

There's a lot in there for the economy: a 'comprehensive decommissioning action plan' for North Sea installations, for instance. The supply chain needs co-ordinated if the work is not to go elsewhere.

A National Manufacturing Institute is being set up, with business and with Strathclyde University. It's part of the attempt to address Scotland's poor record in productivity (shared with much of the UK).

There's to be a new energy strategy. And one for climate change. Aspects of welfare are to be devolved, which has economic implications.

A review is being carried out into the future of Scottish Enterprise and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, and another taking a radical look at business rates.

Business may not like the tone of some workplace reforms, including removal of fees for industrial tribunals. But they may be helped to gain rare skills if the Returners' Strategy can bring more women back into the workplace after career breaks for family.

A planned cut in Air Passenger Duty could face stiff opposition

Air Passenger Duty (APD) is one to watch. Neither Labour nor Greens like the idea of cutting it in half, once it's devolved. It's either an incentive to pollute, or a helping hand to well-off frequent flyers. But business likes the sound of an APD cut - a lot. So do Conservatives.

Remember that Nicola Sturgeon and Derek Mackay, the finance secretary, have to get budgets approved with support from at least one other party, and APD could be an element in those negotiations.

But already, the hot Holyrood topic for business is business rates. Small firms like the extension of the bonus scheme, removing 100,000 of them from the business rates net. Those still in the net complain that the system is not fit for purpose, and needs to be linked to ability to pay.

For large business, a supplement has been applied. On Monday, we got a wide range of businesses lobby groups joining forces in a plea to have that removed, because they say it puts them at a disadvantage over businesses operating south of the border.

There was no sign of movement on that in the first minister's statement to MSPs. It is a campaign that will surely feature in the run-up to the Holyrood budget, with a draft due late this year.

Loan arranger

The biggest rabbit out of the first minister's hat was the Scottish Growth Scheme.

It's quite a big idea, if it can be made to work. And it plays a constitutional tune to the SNP's liking.

If Westminster agrees to give permission for a big increase in the Scottish government's liabilities, that will be another power devolved, under Scottish government pressure. If it doesn't, that will be evidence of how Westminster "holds Scotland back".

The idea is for loan guarantees of up to £5m each, and a total of no more than £500m. This is aimed at medium-sized companies with ambitions to grow and to export.

This is an area where it has long been acknowledged that Scotland has a problem. Its business birth-rate has been addressed (and quite successfully - stand by for more on that next week). But the venture capital to help grow a company is harder to find.

The Scottish Growth Fund looks intended to plug that gap. Getting it to work is perhaps trickier than it looks. It requires government to identify where there is market failure to provide funding. But by doing that, it's likely to take on higher risks than banks would accept.

So should ministers sign off on loans that already have some bank backing, or those that have none?

If none, do civil servants give investment scores to business plans, and assess risk? Do they have the necessary skills?

Do small, fast-growing firms have to tick all the government boxes on living wage rates, social responsibility, gender balance and diversity?

If they do, it can be a distraction from the challenging job of growing. If they don't, then public money is being poured into projects which don't meet the public's priorities.

We've seen these problems before. Well-intentioned, well-funded schemes to help business can come to nothing much if they are too bureaucratic. That growth phase can be one when bosses have to be ruthless with priorities, and the time taken to get public funding can be a reason for not bothering.

State funds

As Brian Taylor has noted, the Scheme requires the approval of MSPs to let ministers and enterprise agencies take decisions about public money for private companies, and to do so in private.

It requires approval from the Treasury for this to be allowed on to the Scottish government's books. The loan liabilities would sit alongside public sector pensions.

And ironically, this attempt to offset the impact of Brexit may have to steer carefully through European Union state aid rules, at least until the UK leaves the EU.

According to Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish Growth Scheme is "an exceptional response to an exceptional economic challenge".

But just as uncertainty hangs over the meaning, shape and implications of Brexit, there is now uncertainty as to whether the initial dire warnings might have been exaggerated.

Businesses were in shock when the result came in. They're moving through that now, and at least some survey evidence is getting back to something like a new normal.

Outside the London housing market, consumer behaviour has barely shifted. And sterling is on the rise again.

It's far too early to say that the concerns have gone away, along with the risk of recession and longer-term lowered growth.

There's lots of uncertainty and almost certainly a lot of investment put on hold, while businesses wait to see what Brexit will bring. But for now, it's not bringing as much change as at first seemed likely.

- Published4 September 2016