Weak foundations to lofty ambitions

- Published

Tens of thousands of tonnes are recycled at the plant in Stirling

In Stirling, in one of these commercial estates dedicated to car showrooms and warehouse shopping, and a left turn into the Superglass plant feels a little like a journey into the 1950s.

The brick built buildings, the warehouses and the administration block are little changed from 1953, when the plant began its transformation from a bottle factory, or 1965, when the Queen visited.

There are significant differences, of course. There's the extensive presence of safety measures, painted walkways, strict parking instructions and high-vis jackets. There's a brightly painted "Innovation Centre", with inspirational slogans to "Change the Way you Think".

Also, atop the furnace are top-heavy contraptions that look like giant grain hoppers. They are to scrub emissions from the resin, where 30,000 tonnes of recycled glass is processed and bonded into insulation materials for buildings.

This Kerseland plant was nearly consigned to industrial history, and might have freed up 16 acres of land for yet more of the kind of retail outlet in which the British excel at selling imports to one another.

Broad horizons

Superglass had to re-finance three times in recent years, as it teetered on the verge of collapse. That precarious phase of its history is over now, because it has a new owner, with deep pockets and broad horizons.

The logo on the side is a Russian one - TechnoNicol. It belongs to a sprawling building materials empire controlled by one Sergey Kalesnikov.

He was visiting his new acquisition, to meet the 150 staff this week. He told them that on top of his £8.7m deal to buy the plant, he is investing £4m to £5m on a new furnace, or perhaps an adaptation of the current one, which could be more energy efficient.

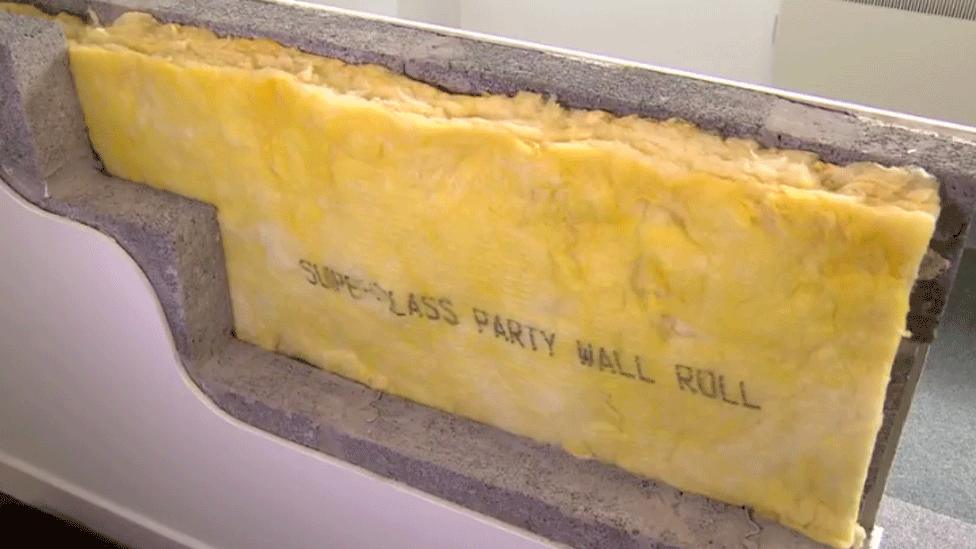

The company turns recycled glass bottles into wall and loft insulation

Either way, the intention is to boost production from 30,000 tonnes per year to nearly 60,000. That's likely to involve some recruitment, on top of the 150 staff now at the Kerseland site.

With less than 10% of output now going for export - mainly to Sweden, and some to Germany and Poland - the aim is to get that up to around 40%.

With TechnoNicol's distribution, through Russia, its Confederation neighbours and increasingly into the Asian market, the task of finding outlets for Stirling's glass insulation should get much easier.

Amid the uncertainty over Britain's future trading relations, it's both reassuring for the Stirling workforce, and perhaps a sign of where future markets may expand.

Who is the new owner?

Russian businessman, Sergey Kalesnikov, stepped in and bought the Stirling company

Mr Kalesnikov's business dream was built on the foundations of a student summer job working as a roofer.

This was the early 1990s, when the market system was opening up new possibilities in the recently deceased Soviet Union.

He could have gone to study in the USA or into business. He chose the latter, because he felt his English language skills were not sufficient for the State's.

Aged 21, he set up in business, made mistakes and learned from them, then to expand his acquisitions into 40 factories around the world, and a billion US dollar turnover, selling in more than 70 countries.

The mainstay products are in roofing membranes, and his factories make 850,000 tonnes of rock wool, a pulverised treatment of rock that serves as a particularly tough form of insulation, with load-bearing qualities included.

Because Russia is a sometimes hostile place to expand sales for outside companies, TechnoNicol has benefited from effectively protected markets, meaning quite generous margins.

Stirling's glass wool is new to the Russian's empire, so Mr Kalesnikov can use that extra capacity and output to supplement his rock wool product range.

150 staff currently work at the Kerseland site

Other products from the Stirling plant are a variation on the loft insulation rolls. New-build houses can have brick cavities insulated with a glass material like cottonwool, made from the same base of 84% recycled glass, supplied from Lanarkshire by Viridor.

The white stuff can be injected in to holes in the walls of new homes, avoiding any need to interrupt the brickies' work for sheets of glass wool. In Sweden, it is sometimes used to fill entire roof spaces. For manufacturers, that means cash in the attic.

Over recent years, the UK government's Green Deal didn't amount to the kind of home energy efficiency subsidy programme on which Superglass's management were banking.

The company had focussed on supplying to the retrofit market, providing glass wool to existing buildings.

The Green Deal was a very damp squib, and that market hasn't taken off. But there's lots of demand for new housing, particularly in the south of Britain. The raised building standards on these homes have pushed more energy efficiency into the mix.

Brexit? What Brexit?

According to Ken Munro, who arrived as a consultant in 2014 and is now the chief executive - continuing under the new ownership - there was a need to shift from dependence on a stalled market.

The result is a recovery, with a £3m swing from loss.

The uncertainty around Britain's trading relations after pulling out of the European Union is no obstacle to the deal and the expansion.

Asked about such political issues, Mr Kalesnikov bats them away as having no effect on him. That may be a wise approach if your main operations are in Russia.