Big Budget choices - the debate starts here

- Published

It's a budget, but not as we've known them. Not in Scotland, anyway. And rarely in Westminster either.

We knew things were tight financially. But the level of uncertainty and budgetary change is unprecedented.

So the publication of a paper setting out the big picture for the Scottish budget this year, and for the rest of the current parliament, is a pivotal moment in the life of the nation's politics.

Let's look at the background. The 2017-18 Budget at Holyrood was on course to become a further tightening of the austerity screw.

Not that the austerity screw was applied as tightly as former Chancellor George Osborne wanted you to think it was. But there have been real cuts of around 5% since the financial crash, the Great Recession and the departure of the Labour government.

Now, we've got a new Chancellor. He's said he's going to "reset" the budget. Philip Hammond's Autumn statement is on 23 November.

And if he continues to say no more than that, we're all in the dark as to what he's going to do. Is a reset a re-working of the numbers, so as to assume lower growth than we expected at Osborne's final budget last March, and still to turn the budget into a surplus by the next Westminster election?

Is a reset a re-calibration to assume that new circumstances will leave the UK finances still in deficit by 2020, with the surplus target postponed into next decade?

Or is a reset a return to factory settings - a rethink in the light of new evidence that the economy will need a stimulus in order to avoid a recession or at least very slow growth? Mr Hammond surely won't admit it, but the latter two might look very like the plans set out last year by the Conservatives' opponents in Labour, the LibDems and the SNP.

And why this change in circumstance? Well, that's Brexit, of course. As a result of that referendum vote, all but one economic forecaster (Patrick Minford at Cardiff University) assumes the economy will grow more slowly than it would otherwise have done. That means lower tax revenue, with perhaps higher unemployment costs.

Tax take

There are more yet changes afoot. There's a new government in place at Holyrood. It may look quite like the previous one, but it's got a new manifesto to implement. And some of that was quite pricey.

It has to push that through with a budget process delayed by Philip Hammond's reset. Derek Mackay can be expected to publish a draft by Christmas, followed by only around two months to get the legislation passed.

Unlike the past five years, he needs to get support from at least some opposition MSPs. And the SNP thinks it faces a tougher task in doing that than it did in minority government between 2007 and 2011.

The other big change is that Mr Mackay has a lot more tax powers at his disposal. Not as many as he'd like, to be sure. But substantial all the same. The arrival of half of income tax-raising, and then all of it, will require the Scottish government to forecast the impact of changes to tax and growth trajectories.

There could be relatively minor tinkering, such as a freeze on the threshold at which upper rate tax begins to be paid, while Westminster has plans to increase that well above inflation. The more significant ones will have a more significant impact, in changing the assumptions of what income tax the new Revenue Scotland can expect to collect.

And then there's growth. If that remains sluggish, and lags that of the UK, as it has been doing for the past 18 months or so, then a gap begins to open up in comparable tax revenue. It may not look like much at first. But as the Fraser of Allander Institute has illustrated, a continued growth gap has a big effect over time - in Scotland's favour, or against it. (The growth gap has rarely been in Scotland's favour.)

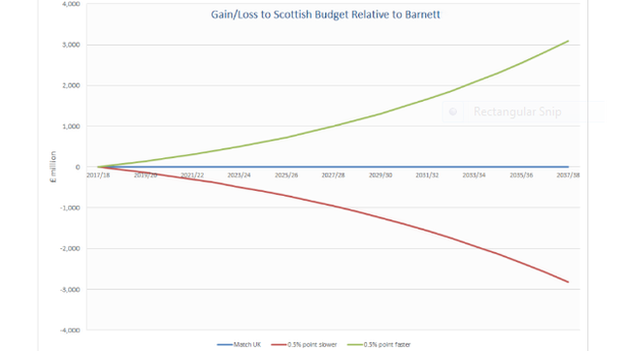

What would happen with 0.5% more or less than Westminster in tax growth?

This shows what happens with a gap in the growth of tax revenue of 0.5% per year. After 10 years, it means a difference of around £1bn. The reward, in other words, is that Holyrood could be £1bn better off in 2026 if it can step up Scotland's growth by a modest amount. Or if it fails to, and continues to lag, then it's £1bn short of where it might otherwise have been.

An interesting point was raised at the conference in Edinburgh to discuss this new report. Growth doesn't always feed through to tax revenue, or at least not proportionately.

The director of the Institute of Fiscal Studies, Paul Johnson, was on hand to point out that recent growth in the UK jobs market has been great for bringing people into employment, but not at raising tax. Lots of new jobs with low pay doesn't feed through to revenue for the Treasury, whereas enhancing the earnings of those on high pay is very attractive to the taxperson.

There are difficult choices there. The drive for lower inequality has a trade-off with the drive for healthier public finances, without which those at the rough end of inequality are more likely to suffer.

Reset to factory settings

All this assumes that the current fiscal framework, through which the block grant from the Treasury to Holyrood is calculated, holds past the review which is due in five years. Fiendishly complex and open to competing interpretations of incomplete data, it may need reviewed before then, in light of European powers coming to Scotland.

Assuming, for instance, farm subsidies move out of Brussels, the Scottish government will want a lot more than a population share of that budget if it is to retain payment levels to Scotland's more subsidy-dependent agriculture sector.

So with all that - austerity, Brexit, new powers, a new mandate with a new manifesto and minority government - where does that leave us, according to these Strathclyde economists?

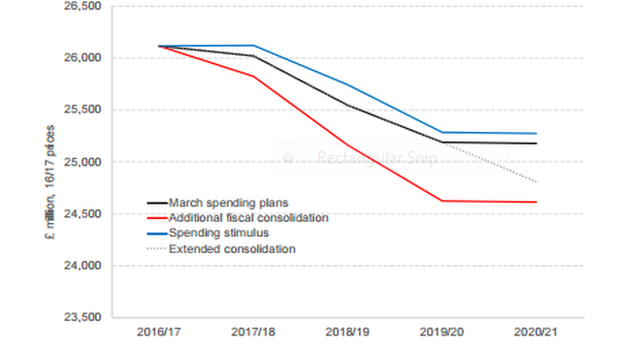

This chart illustrates it. The middle line shows what happens if Philip Hammond sticks to George Osborne's numbers in March?

Three scenarios for Holyrood spending

The upper line shows what happens if there is a modest stimulus, and the Osborne rules are relaxed.

The lower line shows what happens if Mr Hammond is determined to push on with the austerity project, and get to a surplus by 2020. With the numbers in real terms, you can see a gap opening up of up to £1.6bn. Whichever it is, it's a cut.

SNP manifesto

Let's go back to the SNP manifesto. The new analysis assesses the choices the SNP government has made for itself. It's promised NHS spending should rise by £500m more than inflation over the course of this five-year parliament. There's a big commitment to expanded childcare, costed at £869m by 2020-21.

There's a promise to retain police spending. Student tuition fees and numbers look untouchable, and with promises in widening access, there is pressure to increase places available.

Education attainment in schools is a high priority for the first minister, only some of which can be funded from the higher council tax on owners of bigger homes.

The Allander audit of promises goes on, and on. Mental health is to get another £150m per year. College numbers are to be retained. More modern apprenticeships. Continued concessionary travel, with the number of pensioners rising and apprentices to be included.

More pensioners also puts more pressure on the health service. That £500m extra spending is not likely to seem like enough, given pressures on the system.

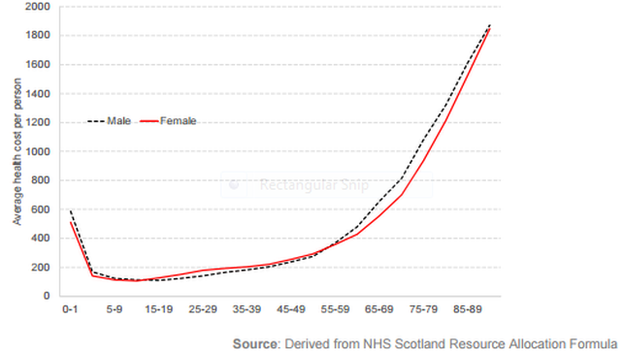

And here's an interesting aside - the chief medical officer has this week suggested that doctors might like to think twice before using every means at their disposal to keep people alive when their lives are clearly nearing the end. That's a very difficult public policy discussion to have, but it has a direct link to future NHS spending. The Allander report has a chart that shows just how much health spending goes up with old age.

Health costs per head, by age and gender

The devolution of welfare powers - £3bn worth - brings expectations of how much Holyrood can protect Scots beneficiaries from the Treasury's tight squeeze, much of which is yet to be felt.

There's the cost of implementing that administratively, which these economists warn can be expected to come in above estimates. That's based on past experience of setting up other, very complex systems. Simply measuring what's going on in the Scottish economy, so as to be able to make good budget judgements, will require a big lift in statistical capacity.

Choice cuts

It's worth noting another change underlying all of this. The Fraser of Allander Institute (no relation, by the way) is providing a significant public policy service in setting out the big picture.

The unit has been beefed up by Strathclyde University, to fill a gap in funded analysis of government spending and the economy, at a time when key figures from the 40 years of Fraser of Allander forecasting and commentary have been retiring.

Newly in charge is Graeme Roy, recruited from the Scottish government, where he was right at the heart of the budgeting process until earlier this year. He ought to know how things work, what doesn't work adequately and where the statistical bodies are buried. So when he says there is a great need for multi-year planning, it's because he's seen the shortcomings of doing things year-by-year. Likewise, his call for a more sophisticated political discussion about the number of police officers, nurses or NHS waiting times. They are easy to communicate to voters, but distract from allocating resources to having most effect within those public services.

The IFS and Allander approach to budget analysis makes no judgement on the political choices at Westminster or at Holyrood. Instead, it takes the known numbers and forecasts, and sets them alongside the public positions taken by ministers, including their manifesto commitments. From that, they can illustrate the scale of the challenge ministers then face.

If it works, as intended - the way that the IFS's "green budget" does, to inform debate ahead of the Westminster budget - that should help inform opposition parties, lobbyists, media, commentators, online trolls and the wider public.

What this does is force people to recognise that, for every spending decision, there is a cost, and money spent in one place can't be spent in another. Similarly, choices can have consequences - linking tax levels to growth, for instance.

Politics can be about positioning, posturing, assertion and, at its best, about the eloquent expression of principle, but government eventually has to be about choices.

- Published13 September 2016

- Published9 September 2016