Unequal Scotland? - How being poor can cut short your life

- Published

The average person from the most deprived tenth of Scots dies aged 73, after 23 years of living in "not good health"

All this week I am looking at how equal or otherwise Scotland is. Here, I examine how long on average we live and I find out that the wealthier in society maintain good health many years longer than those in poor communities.

There are many disadvantages to being in poverty, but the starkest one is that you're on track, from birth, to die younger than others.

That's on average, of course. But it's an average which tells a compelling story about life chances.

What is much starker is that your healthy life, before your health condition deteriorates, is a great deal shorter than that.

It's a factor that means the average person from the most deprived tenth of Scots dies aged 73, after 23 years of living in "not good health".

The person from the least deprived tenth of Scots can expect to die, on average, aged 83, after 10 years of being in poor health.

Why is deprivation so closely aligned with health?

Perhaps the answer to that seems obvious. The most deprived fifth of Scots are nearly eight times more likely to be admitted to hospital with an alcohol-related problem than the least deprived fifth.

But it's a more complex picture than you might think. Solving it is certainly a very complex challenge.

Some symptoms of deprivation include a higher incidence of obesity, poor diet, little exercise, heavy drinking, and drug dependency. A lot of the effort that goes into addressing inequality is directed towards those symptoms.

But the underlying causes, according to public health experts, are a long way from those relatively straight-forward symptoms. They have more to do with the distribution of power, income and resources.

The ability to remain relatively healthy is greater if there is more of an incentive, access to an affordable healthy diet is straight forward, if housing isn't damp and adequate in size, and if air quality is good.

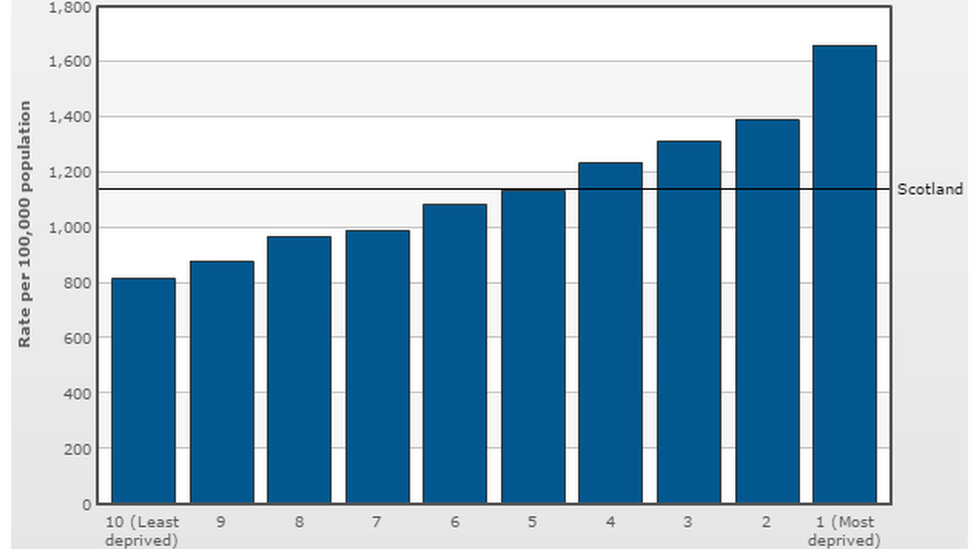

Deaths per 100,000 people 2014 (source: National Records of Scotland/Scottish Population Health Observatory)

Government-backed messages to give up smoking and cut back on alcohol reach a receptive audience within more prosperous Scotland, but are reckoned to be largely wasted on those most in need of heeding them. That, perversely, can widen health inequality.

So said a report into the Scottish government's efforts to tackle health inequality, published in 2014, and prepared by a team led by Glasgow University's Professor Dame Sally Macintyre.

The Health Inequalities Policy Review, compiled by NHS Health Scotland, argued, as others have done, that the starting point for poor health can be global economic factors. They reckon the rise of a de-regulated labour market in the 1980s, with the demise of old industries, brought a sharp rise in health inequality.

The gap was not new. But between the 1920s and 1970s, it had been closing, helped by health care delivered at the point of need, and improvements to housing conditions.

This Friday at 14:00, I'll be hosting a Facebook Live in which I'll be answering your questions on my Unequal Scotland? series. Take part by going to the BBC Scotland News Facebook page, external.

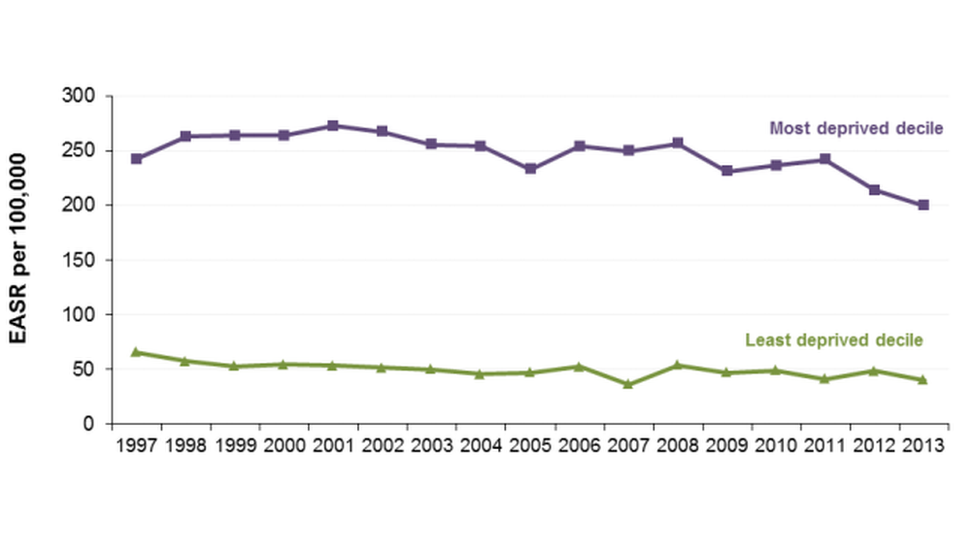

From the 1980s, the gap grew again. While chronic heart disease was tackled as a source of death for more prosperous Scots, it continued to claim many more younger victims in the most deprived parts of society.

As with most other causes of death, the death rate for poorer groups due to heart disease has fallen, but only after a lag. And that helps explain why the health inequality gap has stabilised since 2006.

Are there other measures of inequality?

Life expectancy is a key indicator. Premature deaths tell a similar tale. And one area where the gap has been stubborn has been in deaths, from all causes, for those aged 15 to 44.

The overall figure for that age group has hardly changed in 30 years. And this chart, showing deaths per hundred thousand people in the deprived and prosperous fifths of Scottish society, tells a grim story of disadvantage long before people reach those average ages for death.

Gap in deaths for Scots aged 15 to 44: the least and most deprived (source: Scottish government)

A further measure used in the Scottish government's public health research is for those reporting mental health problems. Between the least and most deprived tenths of the population, there is a five-fold difference. People from the poorest areas are more than twice as likely to go to their family doctors complaining of anxiety.

Audit Scotland took a look at health inequality in 2012, and drawing on the most recently published data at that time, the spending watchdog highlighted several gaps between least and most deprived:

Low birth weight was more than twice as high

Breastfeeding was almost three times lower

Signs of tooth decay in children ran 54% to 81%

Childhood obesity was less of a divider, at 18% to 25%

The teenage pregnancy rate was nearly five times higher in the most deprived areas.

What is the 'Glasgow Effect' and why does it matter?

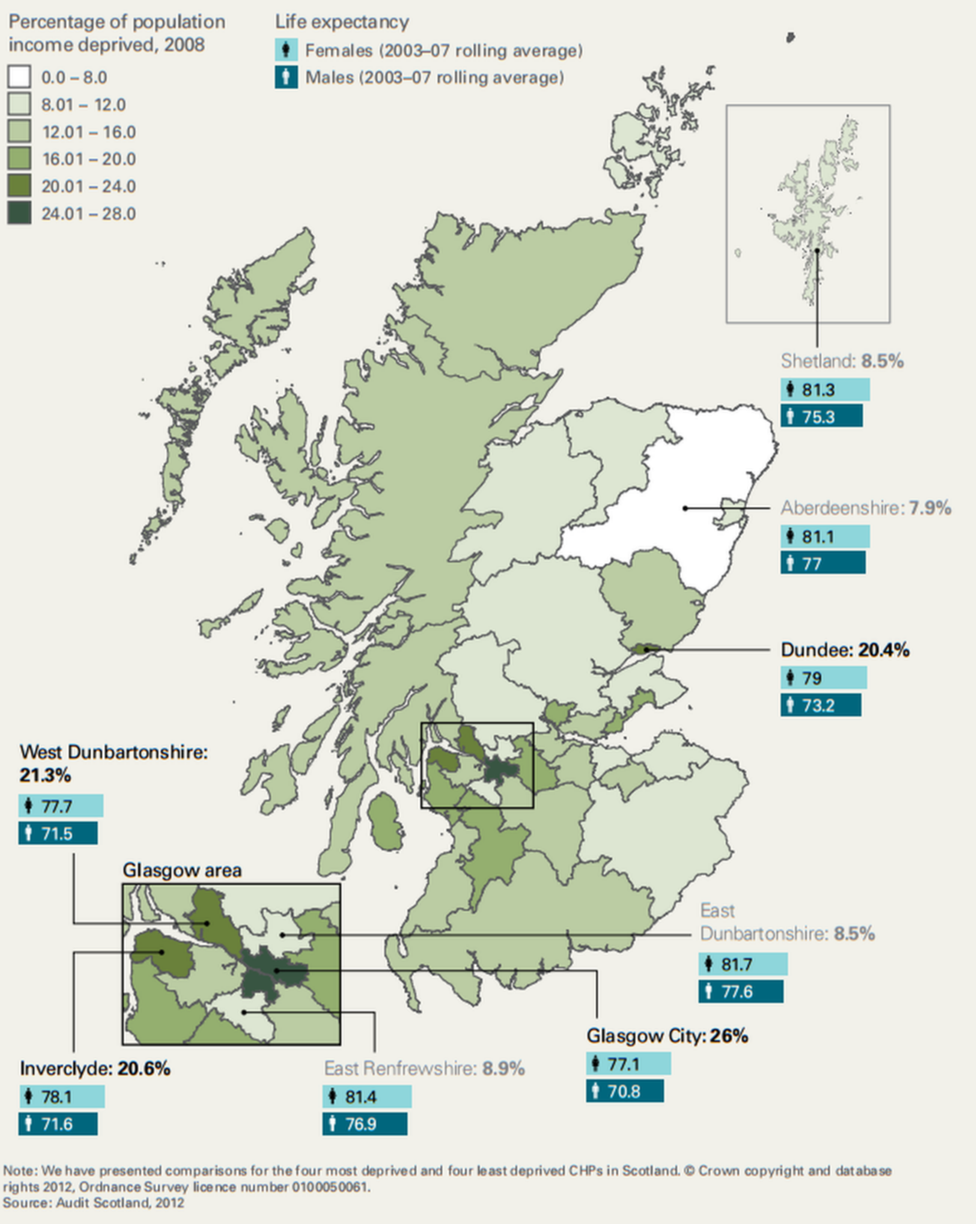

There's a well-established regional pattern to Scotland's bad health. Despite the love of butteries and rowies in the north-east, it contrasts with west central Scotland in its life expectancy.

Glasgow has the lowest life expectancy of anywhere in the UK. Even by comparison with similar cities, which faced similar industrial profiles and economic challenges, the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) says the city's health looks considerably worse. Compared with Liverpool and Manchester, premature deaths in Glasgow are 30% higher.

Glaswegians have suffered from a history of poor housing

Among the baffling element of the Glasgow Effect is that it persists even when statisticians discount for higher rates of drinking alcohol and smoking. And while it affects the more deprived areas far worse, the Glasgow Effect of depressed health outcomes extends to the more prosperous parts of the city.

Earlier this year, the GCPH published a report drawing together the various reasons that have been studied in an attempt to understand the Effect. It concluded that Glaswegians are unusually vulnerable, and mainly due to a history of poor housing.

The starting point was overcrowding, to which the responses were slum-clearance along with new, high-rise blocks and very large peripheral housing estates. They were built to poorer standards than elsewhere and lacked investment for many years.

Scottish Office policy added to Glasgow's problems while trying to solve them: it drew many of the more able, younger Glaswegians out of the city and into Scotland's New Towns. And it is argued that the council's policy of encouraging an up-market, or gentrified, city centre (including the Merchant City) only exacerbated the problems.

How does Scotland compare?

Scottish life expectancy, on average, is lower than England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Health Inequalities Policy Review, two years ago, noted that it is also lower than the rest of west and central Europe.

Countries emerging out of war and poverty in 1945 improved their life expectancy at a faster rate. Some overtook Scotland, including Portugal, Spain, Finland, Ireland, Austria and Italy.

Eastern European countries had poor figures and faced a sharp shock to their established industrial bases after 1989, but quickly began to improve their population health faster than Glasgow was doing.

Inequalities within countries are typically lower than in Scotland. Where data is available across west and central Europe on the unequal position of more and less educated men and women, the only countries with bigger inequalities were Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Lithuania.

What can the NHS do about health inequality?

The National Health Service should be a leveller for health inequalities, and nobody would argue that it hasn't helped. But it hasn't helped enough to close the gaps.

It is sometimes described as the National Illness Service. Resources are heavily skewed towards treating medical complaints after they arise.

Dame Sally Macintyre's report, in 2014, considered the total spend on health and wellbeing by health boards and councils, between 2008 and 2011, and identified only £1 in 40 directed towards tackling health inequalities.

It has also been found that spending per patient at general practitioner level in recent years has been slightly higher in prosperous areas than in deprived ones.

Deprivation and life expectancy. Source. Audit Scotland 2012

That could be changed, by loading more support into practices where patients are most vulnerable. But the demands on the NHS hardly decline as the well-off live longer. On the contrary, expectations are raised of what can be provided and for how long.

In recent years, the Scottish government has since boosted its efforts to push spending towards measures that prevent illness and deter re-admissions to hospital.

In response to BBC Scotland's "Unequal Scotland" series, a spokeswoman said: "Reducing health inequalities is one of the biggest challenges we face as a country, and one we are determined to tackle.

"We're taking action to address the underlying causes of poverty. That means promoting fair wages, raising educational attainment, supporting families, and improving our physical and social environments.

"NHS boards are being asked to make sure those at risk of poverty or inequality are supported, while we are also working through a programme of dedicated individuals to help patients on a one-to-one basis with non-medical problems that are making them feel unwell.

"These are just two examples of the types of action we are taking to ensure everyone has best possible health outcomes."

What other measures are recommended?

That Scottish government response signals that health can be helped by a healthier labour market. And there are many such ways of tackling health inequalities which go well beyond the health service.

But they are radical, expensive and potentially explosive, as they would require a major shift in public spending to tackle inequalities across health, education, housing, transport and much else besides.

Dame Sally Macintyre's report, the Health Inequalities Policy Review, was gently scathing of government for failing to follow through on what it began with its health inequality policies in 2008.

It said that reliance on advertising campaigns and the publishing of pamphlets was not going to be effective.

It suggested more effective measures could range from energy-efficient housing to traffic calming schemes, lower speed limits, vitamin supplements in food, welfare rights advice at doctors' surgeries, free fruit and milk, and intensive support for those at risk, including home visits and quality pre-school day care.

The report suggested restrictions on unhealthy food advertising and fewer alcohol off-licences. These weren't quite recommendations, but the report was not far from saying resources should be shifted where they are most needed, there should be a minimum income for healthy living, and more progressive personal and company taxation.

Whatever party is in power, those are awkward messages. They demand difficult political choices, and taking action on them could be expected to meet significant resistance.

How long can a child expect to live, born in 2014?

Men

Healthy life expectancy:

Most deprived 47.6

Least deprived 72.7

Life Expectancy:

Most deprived 70

Least deprived 82.5

Years spent in 'not good health':

Most deprived 22.6

Least deprived 9.8

Women

Healthy life expectancy:

Most deprived 51

Least deprived 73.2

Life expectancy:

Most deprived 76.7

Least deprived 84.5

Years spent in 'not good health':

Most deprived 25.7

Least deprived 11.3

Source: Scottish government