Police call 'near misses' revealed

- Published

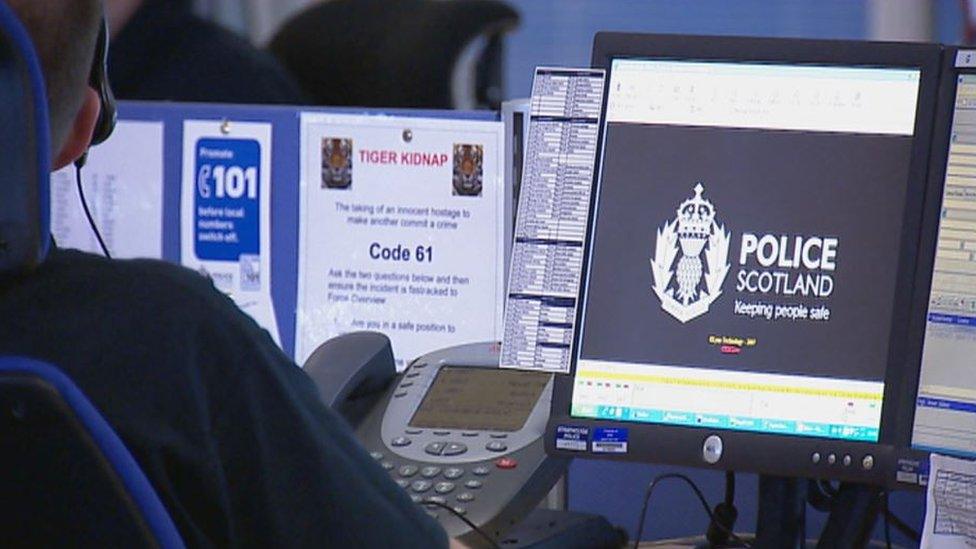

A BBC Scotland investigation revealed 82 "near misses" had been logged in police call centres since April 2016

A BBC investigation has revealed a catalogue of errors in call handling by Police Scotland.

More than 80 "near misses" have been recorded in police call centres since April.

Files show staff mishandled 999 and 101 calls involving road traffic accidents, domestic abuse, assault, self-harm, and vulnerable children and adults.

Police Scotland said these incidents accounted for only one in every 22,500 calls.

The logging of "near misses" follows Police Scotland's failure to act on a 101 call about a car crash on the M9 last year. The crash resulted in the deaths of Lamara Bell and John Yuill.

Ms Bell, who was discovered critically injured in the crashed car, had been in the vehicle next to her dead partner Mr Yuill for three days. She died later in hospital.

A subsequent HM Inspectorate of Constabulary report, external found examples of call handlers being under pressure to end calls quickly and grading of calls being dependent on resources available.

The report also stated staffing levels at Bilston Glen in Midlothian - where the call regarding the M9 crash was received - were insufficient and had resulted in poor call-handling performance.

One of the report's 30 recommendations was that Police Scotland "promote an improvement culture where staff are encouraged to report adverse incidents or 'near misses'".

Forces in England and Wales have also been criticised for call handling.

In 2014 figures revealed more than a million callers who tried to get through to the police 101 non-emergency phone service in the previous year were cut off or decided to abandon their efforts.

Case study: 'Who do we trust?'

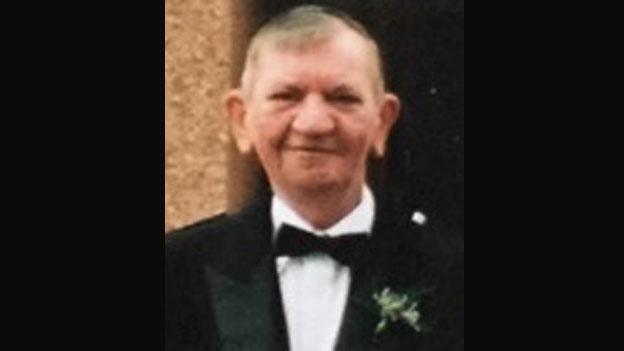

Albert Insch's family are still wondering how different their lives could be. The 72-year-old died alone last month - 19 hours after dialling 999. A carer found his body the following morning at a sheltered housing complex in Inverness

His son, Ally, says police officers initially told him the call centre thought the call was a hoax, and so nothing was done.

In the days that followed, his family were told by a liaison officer that police had actually attended, but they had gone to the wrong address.

Ally said: "Who do we trust? Who do we speak to? How do we find out the truth?

"What we've grown up with is that in any emergency you dial 999, and the response will be there - and in this case it wasn't."

Ally Insch's father died alone last month after dialling 999 more than 19 hours earlier.

The force's watchdog - the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (Pirc) - is now looking into the initial response to Mr Insch's call.

Ally said: "I find my mum at night and she's crying in the kitchen, just by herself, because she doesn't know who to trust.

"She worries about when she dies now - will they [the police] help out."

The Scottish Information Commissioner ordered the disclosure of all the incident reports, external to BBC Scotland after the force denied a freedom of information request.

The documents reveal that 24 incidents were reported in the first month the new reporting system was live - a rate of nearly one incident a day in April.

Another 58 were logged between May and October 2016, with two still currently under investigation by Pirc.

The reports revealed 82 "near misses" which included:

A 999 call to report a road traffic accident where a car was on its side and partially blocking the road, but the dispatcher noted the wrong location. Only after a second 999 call was made were police dispatched to the scene - but an hour later. The report notes: "This incident would not have been dealt with if a second call was not received."

A call was made regarding another car accident where the vehicle was upside down, with people trapped inside. The dispatcher logged the wrong address and the police, and ambulance, attended the wrong location resulting in a delay.

An abandoned - or 'silent' - 999 call was received where an assault could be heard taking place in the background, before the line then went dead. The report notes that "the threat, risk and harm could have been reduced if this call had been identified as a potential crime in action and specifically brought to the attention of the duty officer."

A domestic incident and assault was reported but the dispatcher logged the wrong address which was subsequently passed on to attending police officers. This resulted in "crucial time being lost in maximising [the] safety of the reporter."

John Yuill and Lamara Bell were found in the car three days after the crash was first reported

The mishandling of an email from the NSPCC resulted in a two-week delay in a resource being sent to check on the welfare of a child. This email was only discovered after another misplaced NSPCC email was found. The report noted "not dealing with [the referrals] timeously, or as a matter of urgency, can increase the risk" to "young vulnerable people".

An employee from a gas company forced entry to a property to read the meter, only to discover a dead body. They called 101, but the dispatcher only noted the forced entry and not the deceased which resulted in the incident being given a lower priority of "P3". The report notes P3 incidents are usually only attended after a few hours and "so this call could have been unattended all day". Only by chance were police able to attend sooner, assuming they were only attending a forced entry incident.

A caller made a 999 call regarding a "threat to life" - they called another three times over an unknown period to ask why officers had not yet been dispatched. The incident report reveals the dispatcher failed to clarify the location, and informed the caller there were no officers available at the time to send out. The person in question was later found unconscious by officers.

An operator did not transfer a 999 call, thinking it was a test call. A second call came minutes later stating it was a "genuine full emergency". The subsequent incident report noted "this was a conscious decision by a member of staff not to follow procedure...as the incident was not logged until after [redacted], other emergency services were not contacted".

The documents released by Police Scotland also included 11 'good work' incidents which highlighted examples of good practice by call centre staff.

Deputy Chief Constable Johnny Gwynne, who has strategic oversight of Police Scotland's Contact, Command and Control division, said the new practice of logging "notable incidents" was specifically designed to improve the services the force offers to the public.

He said: "We deal with people at points of crisis every day of the week, every hour of the day.

"Our job is to make sure that we get things right as best we possibly can, and in an imperfect world.

"The men and women sitting in call centres are dealing with somewhere in the order of three and a half million calls a year, and it's a massive endeavour that they have to actually work through that and identify particular risky moments in the volume that they deal with, and make sure that we have the right service at the right time".

'Blame and attribution'

DCC Gwynne added that some of the reported incidents were not down to staff error, but because the caller may have not known the address or may have mispronounced a location.

Calum Steele, the general secretary of the Scottish Police Federation, said that the 80 incidents reported out of 3.5 million calls received by police each year, did not signify a failing system.

He added: "There's no doubt that the culture that's been put in place within the police service and certainly within the call centres, where staff are encouraged now to be able to identify areas where things could've been improved, is certainly much better than the blame and attribution that used to take place in the past.

"The fact that we've got staff with the confidence to be able to put their hand up and say 'look, in terms of an organisational response, we maybe could've done that better', is undoubtedly a good thing."

"In a perfect world no mistakes would be made, but we deal with human beings and human beings, as we all know, with our fallibilities are not perfect individuals and almost any system, no matter what it is, that involves any form of human interaction, unfortunately cannot be deemed to be error-free."

'Culture of learning'

Forces in England and Wales have also been criticised for call handling.

In 2014 figures revealed more than a million callers who tried to get through to the police 101 non-emergency phone service in the previous year were cut off or decided to abandon their efforts.

The documents released by Police Scotland also included 11 'good work' incidents which highlighted examples of good practice by staff.

These included the handling of calls regarding a hit and run, robbery, and pursuit of a stolen vehicle.

DCC Gwynne said the force was ultimately trying to foster "a corporate, conscious culture of learning" whereby staff are encouraged to proactively raise incidents in order to improve the call centre service.

But the 82 reports are all heavily redacted which makes it impossible to determine the frequency of the "near misses", as well as whether particular staff members or call centres are responsible for the bulk of incidents.

However, they do reveal that the same mistakes - such as logging the wrong address - were made time and time again despite repeated reminders to staff about the importance of confirming details with callers.

Analysis also revealed how the "learning the lessons" section of the form was only filled out for half of the incidents.

Scottish Conservative justice spokesman Douglas Ross said: "People expected Police Scotland to sort out call-handling after the M9 tragedy last year.

"However, these figures show there are still significant problems and more communities are worried about the further centralisation planned.

"This should serve as a reminder to the Scottish government that it can't centralise these vital centres which need to be properly resourced and expect the same level of service.

"Public trust in the 101 number is low, and revelations like this will only damage that trust further."

Scottish Labour's Justice spokeswoman Claire Baker MSP said: "It only takes one of these near misses to fully slip through the net for another preventable tragedy in Scotland to happen.

"With the memory of the M9 crash and the tragic deaths of Lamara Bell and John Yuill still fresh, these findings are deeply worrying.

"While I appreciate that these are only a small proportion of total calls received by police calls centres, simple mistakes such as failing to log the right address could cost lives.

"The public want to feel safe in their own communities and that in a moment of need officers will be there."

- Published10 November 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published9 November 2016

- Published9 July 2015