Reconstructed face of Robert the Bruce is unveiled

- Published

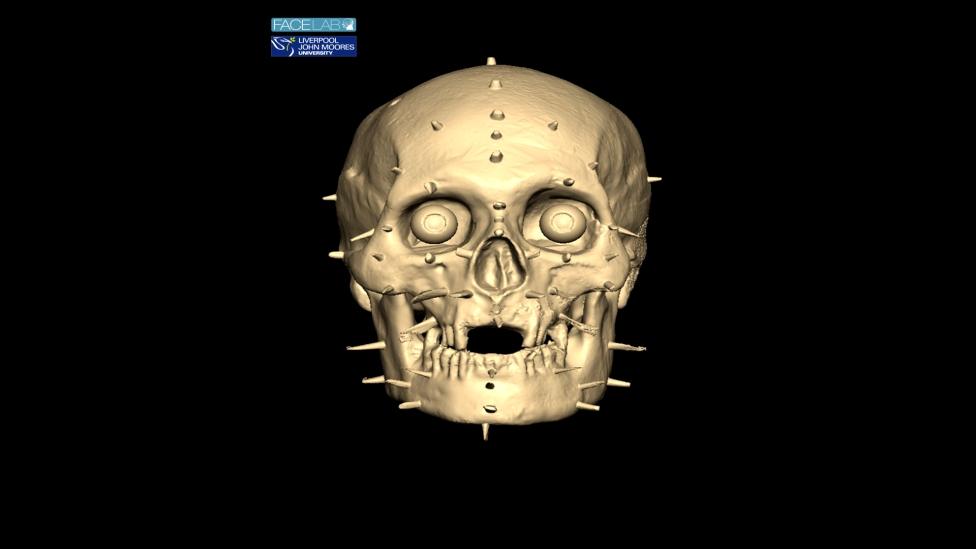

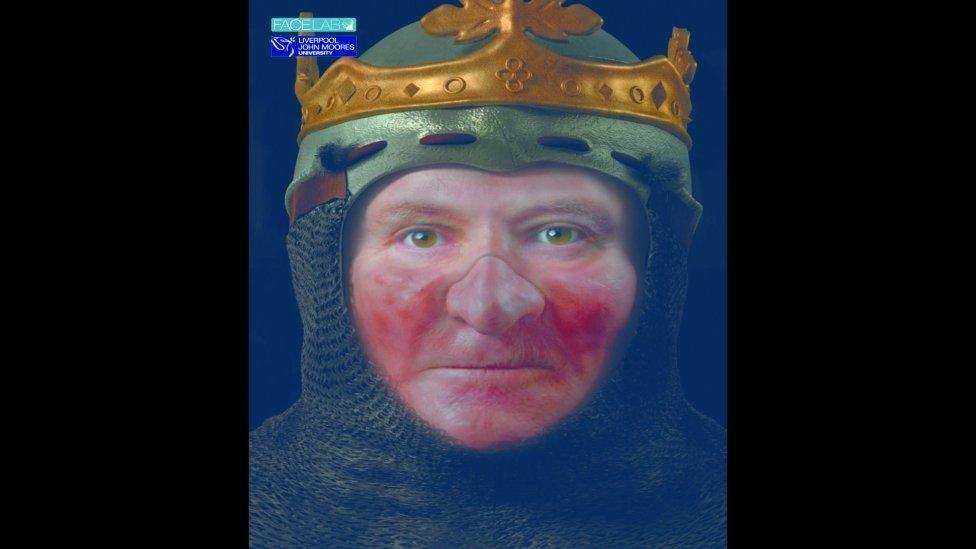

The facial reconstruction is based on images of a skull found nearly 200 years ago

Historians have unveiled a digitally-reconstructed image of the face of Robert the Bruce almost 700 years after his death.

The image has been produced using casts from what is believed to be the skull of the famous Scottish king.

It is the culmination of a two-year research project by researchers at universities in Glasgow and Liverpool.

Until now, portraits and statues of the victor of Bannockburn have relied on artists' imaginations.

With no contemporary artworks to tell us what King Robert actually looked like, historians at the University of Glasgow teamed up with Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) to provide an accurate representation.

Its Face Lab specialises in recreating likenesses from legal and archaeological evidence - most famously, the face of the English king, Richard the Third.

Robert the Bruce is best remembered for his victory over the English army at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

Project leader Dr Martin Macgregor, a senior lecturer in Scottish history at Glasgow University, said he was arguably the most significant figure in the nation's story.

"When he took the throne in 1306 Scotland was in a parlous state," he said.

"Edward I had decreed that henceforth Scotland was to be described as a land rather than a kingdom.

"I don't think it's going too far to say that unless Bruce had succeeded in that endeavour, we might not be sitting here today talking about a Scotland."

Glasgow University's Hunterian Museum holds the 200-year old cast, made from a skull unearthed when Bruce's burial place, Dunfermline Abbey was being rebuilt.

Although they cannot be certain, historians are reasonably confident it is his skull.

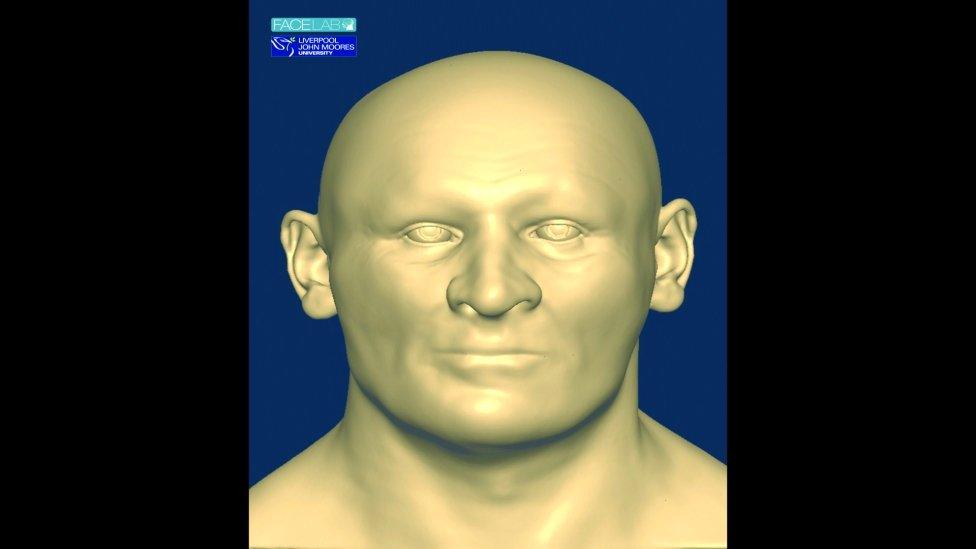

Face Lab uses computer technology to recreate the face from the skull

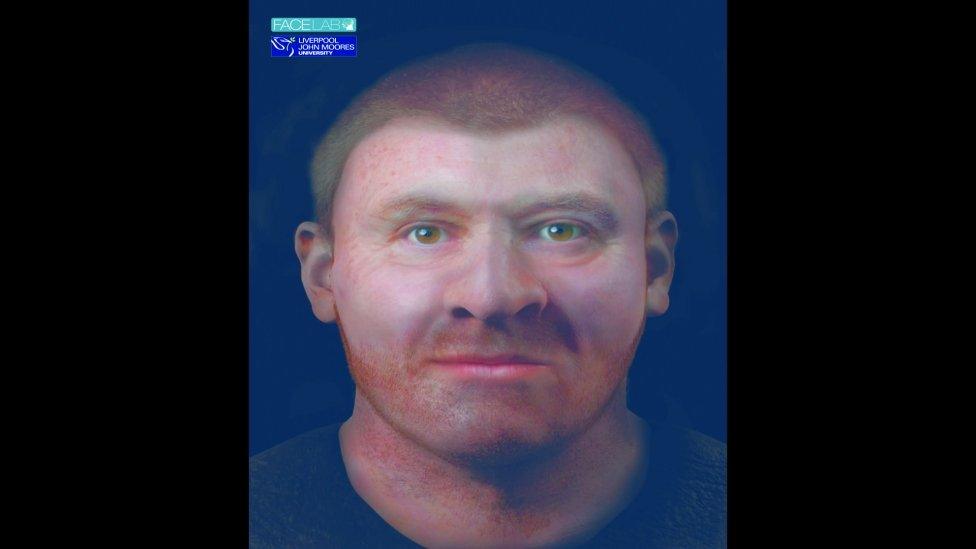

The face was recreated from a cast made from what is believed to have been the king's skull

Robert the Bruce was 54 when he died in 1329

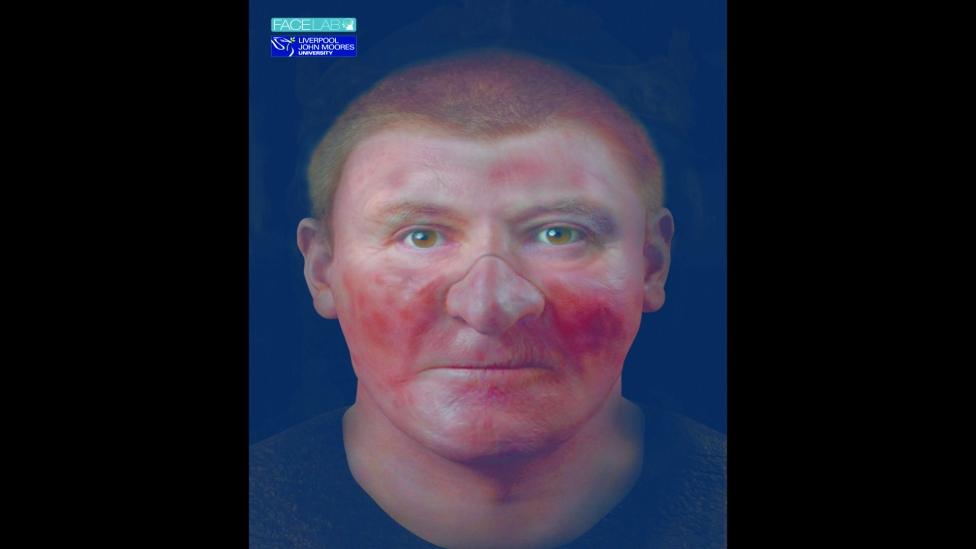

The researchers recreated the king's face with leprosy and without

Robert the Bruce is thought to have had leprosy before his death

Gilded tomb

Bruce's opulent tomb, imported from Paris and decorated with black and white marble and elaborate gilding, was destroyed during the Reformation.

In the early 19th Century, buried deep beneath the abbey, excavators found fragments of black and white marble, some of it gilded.

Below that they discovered a lead-lined coffin containing human remains which included the skull. Those remains were reinterred, but not before a cast had been made.

Two centuries later, the latest digital technology was used rebuild the King's face.

This part of the project was overseen by the craniofacial identification expert Prof Caroline Wilkinson, director of LJMU's Face Lab, in a project that took two years to complete.

"Using the skull cast, we could accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones to determine the shape and structure of the face," she explained.

Robert the Bruce's statue at Bannockburn, where his Scottish army defeated the English in 1314

Casts of the skull found at Dunfermline Abbey are in the Hunterian Museum's collection

What the archaeological evidence did not show was the colour of the King's eyes and hair.

He is said to have been ill prior to his death in 1329, with some accounts suggesting he had leprosy.

For his skin tones, Prof Wilkinson said they produced two versions; one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy.

"He may have had leprosy, but if he did it is likely that it did not manifest strongly on his face, as this is not documented."

'Sense of character'

Dr Macgregor said: "There is a real sense of character in this face.

"Bruce must have been a remarkable man. All of his achievements suggest this to us.

"There must have been tremendous strength of purpose in this individual as well as many other human virtues - flaws as well."

Dr Macgregor said historians should remain cautious about the identity of the skull. More than one Scottish monarch was buried at Dunfermline.

But Prof David Gaimster, the director of the Hunterian, is confident the face is that of the famous king.

"The combination of these magnificent gilded marble fragments and the skeleton itself, the lead wrapping, the depth of the tomb, the location," he said

"All of this information begins to build a high level of probability that this was in fact the tomb of Robert the Bruce."

With Richard the Third there was DNA evidence too but achieving similar confirmation would be problematic.

There exists only one fragment from Dunfermline Abbey which might yield a DNA sample.

But trying to extract the DNA would mean destroying that tiny piece of bone.

There is a well-established principle in such circumstances: leave it. Future generations may find a better way.

It also means that, for all our technological advances, Scotland's hero king will retain some of his mystery for a little longer.

The King's Head - the documentary following the reconstruction from start to finish - will be screened on BBC ALBA on 15 December 15 at 20:30