Queensferry Crossing: The bridge that should never close

- Published

Before the Queensferry Crossing opened in August 2017, its designers claimed it would not be closed by high winds and they have been correct. Instead, an unexpected problem has been detected with ice.

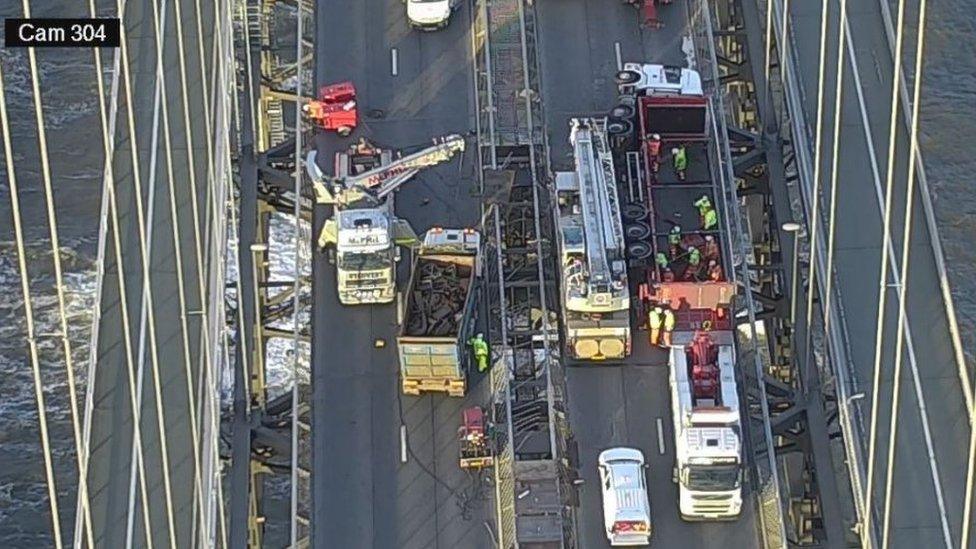

The bridge connecting Edinburgh and Fife was shut on Monday night after accumulations of ice and snow fell from cables on to the carriageway. Eight vehicles were damaged and the bridge remained closed until Wednesday morning on safety grounds.

Mark Arndt, of Forth Bridges Unit with Amey, said the closure was caused by a "unique set of weather conditions".

He said a combination of strong westerly winds along with snow and sleet resulted in accumulations on the main cables. At an elevated height, that snow accumulation became chilled, he said. It then fell to the carriageway as ice.

What's the issue with ice?

Scotland's Transport Minister Michael Matheson said this was the first time the bridge had been closed in the two-and-a-half years since it opened. He said there had been a similar incident last year but the bridge had not been closed.

Mr Matheson said the bridge authorities were in the advanced stage of the process of fitting ice sensors on the cables to detect accumulations.

The transport minister claimed the new crossing had displayed much greater resilience than the Forth Road Bridge had before it.

Mr Matheson said there had been 30 occasions since the Queensferry Crossing opened where the old Forth Road Bridge would have been partially or completely closed.

That is due to the high winds that often batter the Forth estuary.

One of the design features of the £1.35bn Queensferry Crossing was that it was fitted with 3.5m-high baffle barriers to break up and deflect gusts of wind.

The wind barrier was tested on an approach road to the bridge

They were modelled in a wind tunnel by Italian engineers and tested on sections of road near the bridge.

Before it opened, bridge operators said the wind shields should "almost entirely eliminate the need for closures" and that has been the case until now.

The Forth Road Bridge, in contrast, was often closed to high-sided vehicles and HGVs.

Queensferry Crossing - facts and figures

The Queensferry Crossing under construction in 2017

The 1.7 miles (2.7km) publicly-funded crossing was the biggest infrastructure project in Scotland in a generation and carries about 24 million vehicle journeys a year.

The structure is 207m above high tide (683ft), equivalent to about 48 double-decker buses stacked on top of each other.

The steel required for the bridge deck weighs a total of 35,000 tonnes - equivalent to almost 200 Boeing 747s.

Cables can be replaced with more ease than on the Forth Road Bridge - it can be done as part of normal maintenance works without closing the bridge.

The foundations of the bridge are large caisson - circular steel structures - sunk into the mud of the estuary to bedrock level.

The south caisson is the height of the Statue of Liberty. It is 35m in diameter and when it was constructed it was 50m in height.

Stormiest conditions

The Queensferry Crossing is the longest three-tower, cable-stayed bridge in the world.

Designers said wind shields along each side of the bridge were tested against the stormiest of conditions.

Before it opened, Mike Glover, technical director for the Queensferry Crossing Project, told BBC Scotland's Brainwaves programme one solution considered had been a solid barrier to stop the wind getting through.

However, he said that would have changed the dynamics of the bridge "quite dramatically and not positively".

"So what you have to do is create a wind screen which accepts the fact that air pressure will come through," he said.

"You are creating a permeable screen through which some of the air comes but the rest is scooped up and over the bridge."

Waves and spray lash the shoreline beneath the Queensferry Crossing

Bridge expert Alan Simpson, a past chairman of the Institution of Civil Engineers Scotland, external, said the barriers were "more like a thick hedge than a wall".

Other more modern long bridges in the UK, such as the Second Severn Crossing, opened in 1996, have some wind shield protection, usually on either side of the bridge towers. But the Queensferry Crossing has wind shields across its full length.

Mr Simpson said: "The wind on the Forth is so strong in comparison to the other major bridges. We are talking about a bridge at the same latitude as Labrador in Canada."

Building a major bridge at such northerly latitudes and in such an hostile environment was a difficult test for its designers. But they had not reckoned with the circumstances that created icicles on the cables.

The Queensferry Crossing (left) has been far more resilient than the old Forth Road Bridge (right)

Ice build-up of this kind has not been an issue on the other Scottish cable-stayed bridges, Erskine on the Clyde and Kessock, near Inverness.

Transport Secretary Michael Matheson also pointed out that the ice accumulation was not a problem during the so-called Beast from The East, one of the worst weather events to hit the country in years.

He said it was a very "limited set of circumstances" that led to the problem.

Mr Matheson said the bridge operators were looking at the problems experienced by similar bridges around the world in a bid to mitigate against the risk.

One of the suggestions is "collars" released down the length of the cables to clear ice accumulations, which have been fitted on the Port Mann Bridge in Vancouver, Canada.

"One of the challenges is that there is no single solution." the transport secretary said.

"They all have to be designed and developed on the very specific circumstances that the bridge is experiencing."

In the meantime, the politician said work was being taken forward to introduce ice sensors in the coming months.

However, he said: "Ice sensors will not prevent ice and snow building up on certain occasions. They are there to provide a warning."

Time will tell whether this leads to more closures in the future.

- Published11 February 2020

- Published27 August 2017

- Published30 August 2017

- Published15 November 2016

- Published11 January 2017