Scotland's economy: Mind the gap

- Published

Grim: the most common word used by those reflecting on the latest Scottish economic data.

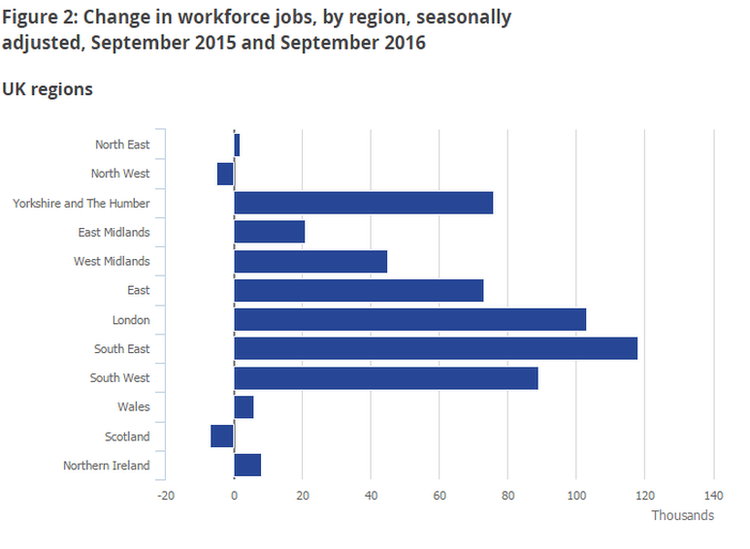

The job numbers could be worse, with unemployment on a downward trend, most recently at 5.1%.

But the most recent figures, for autumn, are worse than summer, when they could be a lot better. Across the whole of the UK, they are.

The British economy has been a job-creating dynamo as it clambered out of the Great Recession trench.

But much less so in Scotland.

In the year leading up to the September-to-November survey, published this week, unemployment fell by 12,000. That's good.

But of those aged 16 to 64, the number of people in work fell by 49,000, and the number inactive and not making themselves available for work was up by 59,000. That's not so good at all.

There have been some more promising numbers recently. For instance, a Bank of Scotland survey found the number of new business start-ups was down in Scotland, but by far less than the UK. Relatively good.

The Purchasing Managers Index for December, from the Bank of Scotland and Markit, edged above the point at which it returns from contraction of output to very modest growth. Good, but only just.

That's while the quarterly survey out today from the Scottish Chambers of Commerce is "finely balanced". Firms were more likely to be positive about the fourth quarter of 2016, except in the (very large) finance and business services sector.

So yes, there are signs of resilience about the Scottish economy that were not evident this time last year. But it is precarious.

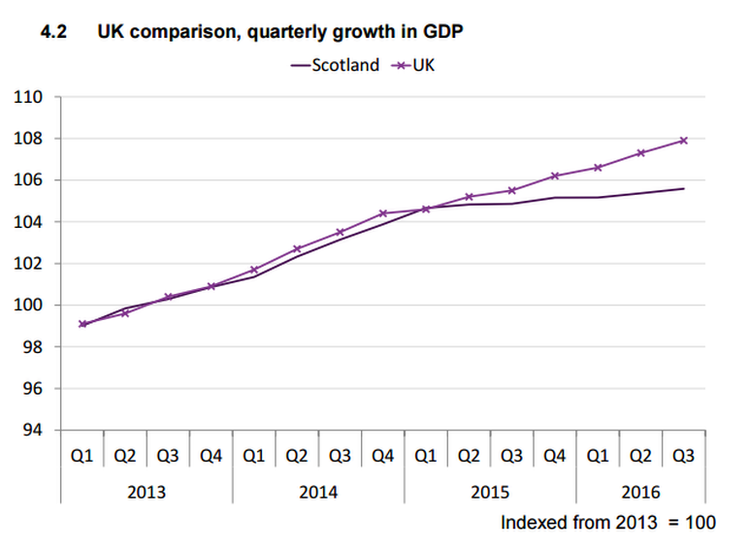

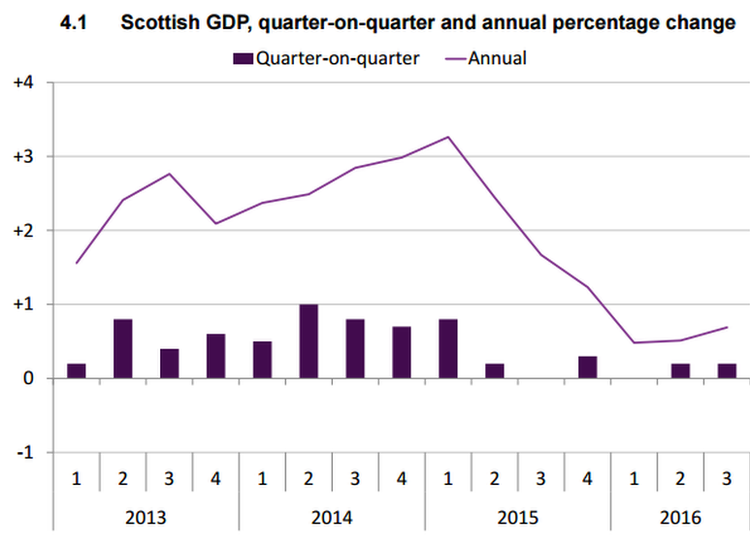

For two years, there has been a clear divergence in growth between Scotland and the rest of the UK. That's growth, as in Gross Domestic Product, and as measured by Scottish government statisticians.

Remember that gap matters far more when it translates into income tax revenue. If Scotland can't keep up growth, receipts will, over time, fall behind the amount that would otherwise have come from the Treasury.

And the weakness of the growth has begun to look quite sustained. Over the past six quarters, two have seen no growth, and three have seen a paltry 0.2% (the more positive figures for April to June last year have been revised downwards).

In the most recent quarter, and over the past two years, Scotland's economy has been growing at about a third of the rate of the UK as a whole.

The business view of this is becoming increasingly concerned and impatient. That is particularly as it watches Holyrood budget negotiations focus on options for increasing tax and shifting priorities across public sector spending.

Nurturing economic growth, which can be helped by decisions taken through the tax system, as well as training and infrastructure, does not seem to be getting the highest priority across the Scottish Parliament.

And amid the febrile atmosphere of Brexit, the UK government has less headspace or political capital available for the economy.

Indeed, this week's speech from the prime minister explicitly chose the curtailment of immigration over the optimisation of economic growth and prosperity (that's in the eyes of the vast majority of economists - other opinions are available from a smaller band of Brexiteer economists).

'Active growth'

The other response is to question whether Gross Domestic Product matters as much as economists say it should.

The Scottish government has a project running to find other good targets at which it can aim. The Office for National Statistics is trying to develop a wellbeing index, much of which seems to be aimed at subjective responses to surveys about sentiment.

Meanwhile, from Scots economist John McLaren comes a refinement of GDP, to "active growth".

An alumnus of the civil service and Labour government, he says we can better understand the underlying trends in the Scottish economy if the noise is stripped out of the statistics.

So no more "administration and defence". Although health, schooling and justice are highly important to the economy, their output is notoriously hard to measure meaningfully.

Gone too is finance, for which it has proven difficult to measure output with much accuracy.

And construction is seen, by this reckoning, as investment. It has also been a very important part of keeping Scotland out of recession over the past two years.

Sector services sluggish

What's left? "The private sector, day-to-day activity, including manufacturing and non-finance services," says McLaren - "the active elements of the economy rather than the 'passive' public services."

By that reckoning, the active economy grew at 6.6% between 2008 and 2015, slightly faster than the Scottish economy as a whole, but while the UK "active economy"' grew 12%.

Since the start of 2015, Prof McLaren says that active economy has contracted slightly, whereas for the UK, it has grown by more than 4%.

And adapting the most recent Scottish government figures for July to September, the active economy contracted slightly over the preceding quarter and by slightly more over the previous year.

The main explanation is that private sector services have been sluggish in Scotland - much less so south of the border.

The notion of measuring the "active economy" is not officially approved, or statistically road-tested. It isn't so easily comparable as straight-forward GDP. It dodges the challenge of trying to measure output from public services.

But it is another way of seeing that Scotland's economy is at best precarious, and seems to have deep-seated problems.