Economy report: Could do better

- Published

At times of uncertainty about the economic direction of travel, it can help to take one's bearings.

That's not always easy for those watching the Scottish economy. The data available is either not that plentiful or not wholly reliable.

But by happy coincidence, a whole lot of information has been published in the past few days that makes this as good a time as any to do some stock-taking.

Here are a few of the things that caught my eye......

Job prospects - Unemployment's down, by 27,000 over the whole of 2016. After a rocky year, and economic growth at only a third the rate of the UK as a whole, the jobless rate is nearly back into alignment with the rest of the UK At a notch below 5%, that's pretty good, in the circumstances of the past decade. Or by any circumstances. Unemployment went up slightly in October to December, though the Scottish government preferred to focus on youth unemployment, which - according to this data - is the lowest of any European country other than Germany.

Flexible friends - So employment must be up? Well, no. It's down 20,000 during last year. Most of that change has been among men. That much was supported by the evidence of the monthly survey of recruitment consultants from Markit, external, which showed January was much weaker for permanent job starts. Contrast that with the whole of the UK, which saw a rise in the number of people in work last year of 302,000. More than half of them were women working full-time. The south of England has recently been an astonishing job creating machine, much of it fuelled by immigration and by a flexible labour market. Many of those bunched at the lower-paid end of the jobs market are not celebrating that flexibility, as the price they pay is in insecure working conditions. And quite a few of them are blaming immigrants for that plight.

Inactivists - How can we have a fall in the number in work, as well as the number out of work? With a shrinking labour market. There has been a striking rise in the number of people who are not in work, and not available for work. They're called "economically inactive". A lot are quite active, being students or looking after family, young and old. The number of early retirees has dropped a bit. And the Fraser of Allander Institute notes that there has been a significant rise in the number of people telling the labour market survey that they're ill, and for the long-term. That might have something to do with the way the welfare system works - or doesn't. When asked why they were economically inactive, the other group with rising numbers is "other". Statistics can be so frustrating.

Patchy work - The jobs picture is patchy. That ought to be no surprise. But those Fraser of Allander economists have delved into the numbers, external to see that Glasgow, Fife and Highland council areas each lost more than 10,000 jobs between 2007 and 2013. They found that more than half the 32 council areas had fewer jobs in 2016 than in 2007. North Lanarkshire, and the oily bits of the north-east and northern isles fared much better (this was before the oil price crashed). If there's any pattern, it is a weak pointer to relative problems for more rural parts of the country.

Real squeeze - Pay is rising, but will it soon be caught up by price inflation? We learned last week that price inflation reached 1.8%, while pay rises in the same year fell back to 2.6%. If that gap narrows and reverses, we're looking at falling real spending power. That makes for unhappy workers and cautious consumers.

Shop drop - After an uncharacteristically merry Christmas at the tills, Scotland's retailers reported that January was, at best, "dreich". That sort of redefines the word as a description of not just grey drabness, but of decline. The Office for National Statistics backed that up at a UK level, with poor consumer figures. The pound duly weakened.

Pay packet - But hang on. It's not so miserable. There are new figures, dug out by Scottish Parliament library staff, showing Scotland's pay has grown faster than any other part of the UK, external except Northern Ireland and north-east England. That leaves it in third position for median pay, after London and south-east England. This is a measure of the pay for the person in the middle of the full-time pay distribution, who has precisely the same number of people earning more and earning less. From 2008 to 2016, Scotland moved up from fourth to third position, just overtaking the east of England. Well, it's an improvement, at least - unless you're an inward investor looking for competitive wage rates. Scotland's median full-time pay stood last year at very nearly £28,000. That's £2,000 more than Yorkshire and Humberside.

Catching up - That's fine if the average worker is producing lots. "Productivity is growing at four times the rate of the UK," we've been told. Sounds good, except that it's four times very little. This matters, though, as productivity is the only way of improving levels of prosperity in a sustainable way. If we want to have more stuff, economically-speaking, we need to produce more per hour worked. Slightly more significant is that Scotland, in 2015, nearly closed the productivity gap with the rest of the UK. But again, there's a catch: the UK productivity performance has been very disappointing. As the chancellor has pointed out, it takes the average German worker four days to produce what the average British worker produces in five. New Scottish government figures suggest the sectors improving their productivity most include business services and finance. That's a very big sector, ranging from paper clip supply to asset management. A much sharper rise was noted in construction, but with a statistical health warning. Manufacturing is important, and has a symbolic power far beyond its share of national output. But productivity improvement there has not been impressive in recent years. The challenge of improving productivity remains probably the key challenge for the Scottish and British economies - though the Brexit negotiations could throw up even more challenging ones. The answers lie somewhere around investment in equipment and in skills, utilising the skills people have better, encouraging innovation, and - tying all that together - the quality of British management.

Exports ail - Scotland has a growing imbalance of exports and imports. Again, according to Scottish government numbers, we're importing a lot more, and failing to export enough, external. Manufacturing exports fell more than 5% in the year to last September. Whisky might have picked up last year, after its export growth stalled, and salmon is riding high on high prices (but watch out for those sea lice hitting supply). The weakened pound is not an opportunity to be missed for turning around that underperformance.

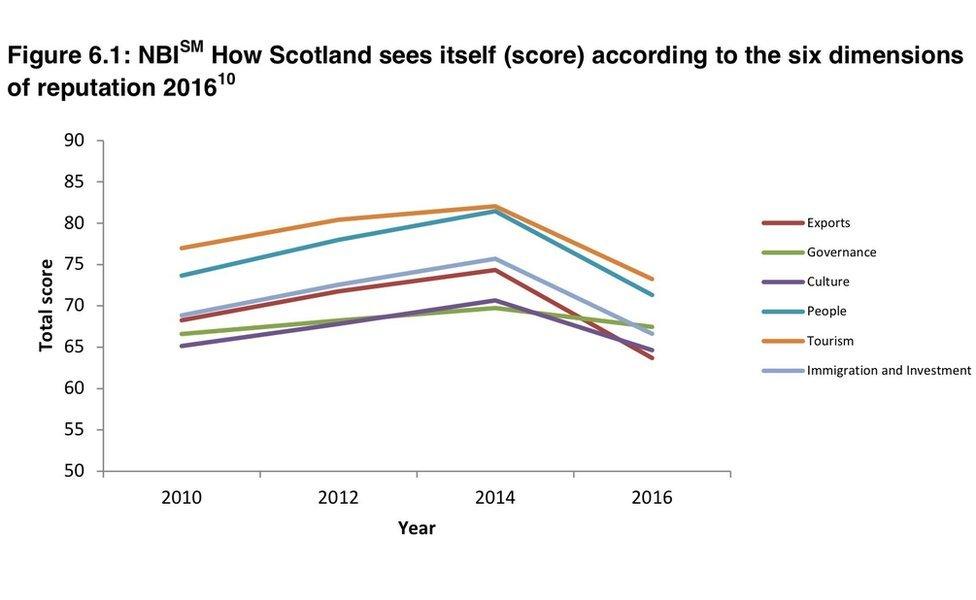

Mirror Mirror - Exporting was the worst of six factors considered in a regular survey of the way Scotland is perceived in the world. The country did much better in governance, and wasn't too bad at its tourism offer. It doesn't do so well in a category called "immigration and investment". These are the findings of something you've probably never heard of, snappily called the Anholt-GfK-Roper Brand Nations Index, external. Fifty countries are assessed on how they are perceived. Scotland contributes to the process, to see if the Scottish government is "improving Scotland's reputation". It's been asking the question since 2008. There's been an improvement, but it's a barely perceptible one. And looking at the change between 2014 and 2016 surveys, it's interesting to note that the UK as a whole gained a more favourable impression of Scotland, while Scots themselves did not. Now, you might think that any attempt to improve Scotland's reputation would do well to start with Scots' opinions of themselves. But while others remain relatively positive about Scotland, it seems that Scots have taken a look at themselves, and more of them don't like what they see. Having asked Scots about themselves every two years, the study concludes: "The attributes which declined most were willingness to live and work in Scotland, how welcome people feel in Scotland, and how friendly Scottish people are". It's probably best if I leave you to figure that one out for yourselves.