Royal Familiar

- Published

Let's start with the good news about RBS. Don't worry. This won't take long.

Er, it's not doing too badly at its drive to get more women into senior executive roles.

Um, it's had a bit of a windfall from Brexit, as currency volatility has seen business customers reach for its foreign exchange hedging products.

It's embracing the future of digital banking. Three-fifths of personal customers have accessed their products through digital or online options in the past 90 days.

One-fifth of customers only use those options. The customer app is the means of lodging 8% of loan applications. Four-fifths of business customer transactions are now digital.

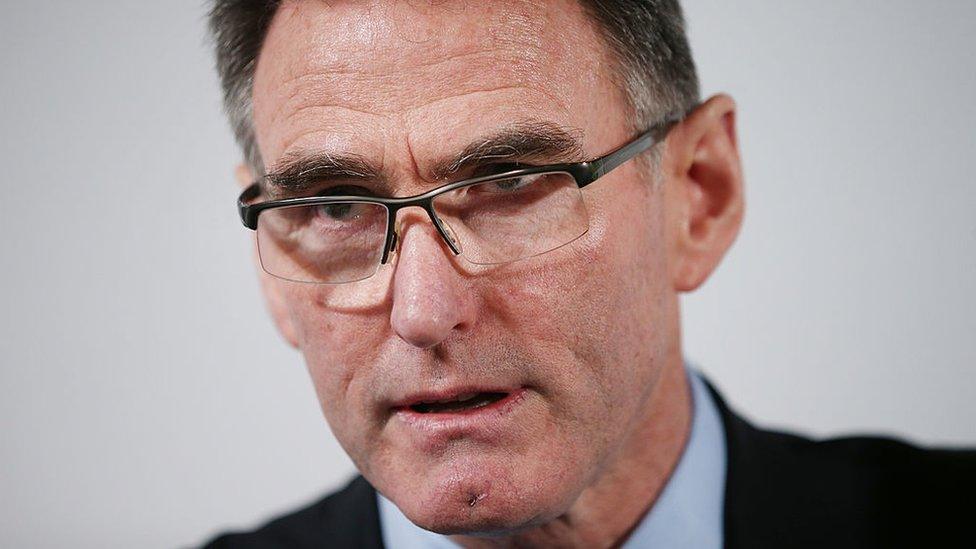

And to be fair, the core bank - the nice bits - has turned in a handy-looking operating profit of £4.25bn. It's "amazingly strong", says chief executive, Ross McEwan. It's not growing much, though - up 4%.

And that brings us to the, er, less good news. That profit is massively cancelled out by the ongoing nightmare of litigation, fines, investigations, restructuring, impairments, redress for mistreatment of customers, mis-selling financial products, and failed divestment efforts.

It's eight years since RBS was reporting a record loss of £24.1bn. That seemed bad. We didn't know that would be the first of ten mega-losses, totalling nearly £60bn, and that eight years later, the loss would still be at £7bn.

BBC business editor Simon Jack has been hearing from insiders about how things might have been done differently.

RBS chief executive Ross McEwan said last year that 2016 was going to be a "noisy year" for the bank

Mr McEwan said last year that 2016 was going to be a "noisy year" for such problems. He wasn't kidding.

The idea was that it would get the problems out of the way, making 2017 a much happier and less noisy year. But they go on - some unresolved, some bringing in new costs.

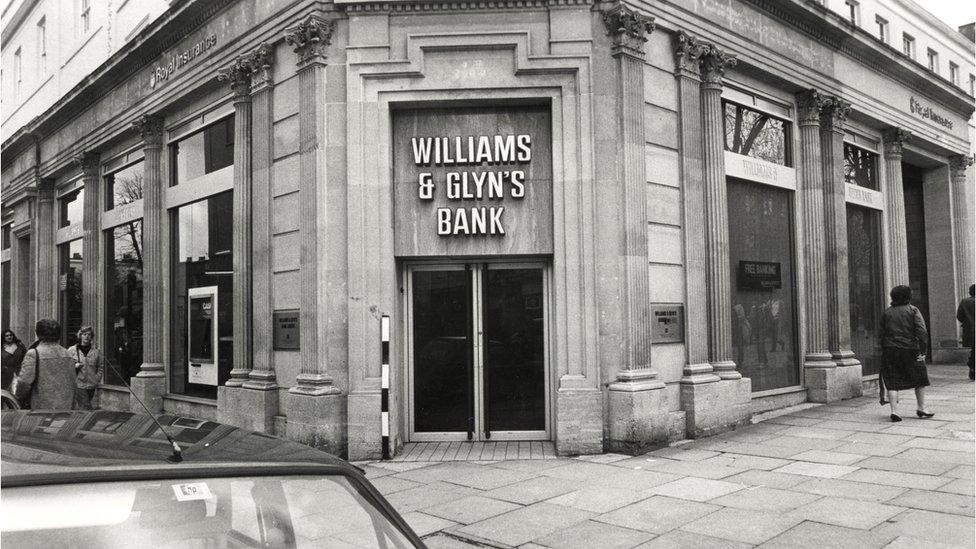

Williams & Glyn has turned into its latest horror episode. This is the division split off from the bank as a European Commission condition for the £45bn of UK state aid.

It's not RBS's fault, therefore, though it has to take some responsibility for botched execution.

Williams & Glum

The split seemed a good idea at the time, helping improve the amount of competition in the UK market. But it has been immensely expensive to clone and split the IT platform, at a time when these are becoming ever more complex.

It wasn't that attractive to potential buyers. Capital requirements have grown. And with interest rates low, generating poor returns, RBS had to conclude that it wouldn't be strong enough as a standalone bank to get a licence.

The Williams & Glyn brand disappeared in 1985, but the unit continues to be an important lender for small and medium sized businesses

The cost until last year was pushing up towards £2bn. Now, the plan has been abandoned. Instead, if the European Commission gives its approval, which looks very likely, RBS is writing a cheque for £750m, to go into an independent fund for smaller challenger banks to poach its customers.

But then, there's another £1bn of costs associated with the project in 2017. And a further £1bn across the next two years. RBS now has a division which it needs to re-integrate, with more than 300 surplus branches, many of which probably duplicate its core network. So sorting out that property portfolio is going to be 40% of the cost.

Vigorous cost-cutting

There has been a huge amount of work in slimming and simplifying the bank. But just like its Gogarburn headquarters, to the west of Edinburgh, its cost base is still geared to a much bigger operation. That is measured by the cost: income ratio - a key metric for any bank, watched closely by investors as a signal of efficiency.

It has come down from 72% to 66% in the latest figures. But the target is 50%, and Lloyds Banking Group - the other bail-out nightmare eight years ago - this week reported that it's already got there.

There are two ways of improving that ratio. One is to increase income, the other to reduce costs.

The options on increasing income are not looking that favourable as the economy slows. So the bank has returned to a vigorous programme of cost-cutting. It's down £3bn in three years. The pace slows a bit from now, but there are still £2bn to be cut within four years.

That almost certainly means job losses. A newspaper story recently speculated on 15,000 jobs, which looks credible.

Toxic

The cost-cutting targets and the aims for better return on equity are being pushed back a year, to 2020.

The resulting atmosphere inside RBS may be one reason why the bank is not reaching its targets on employee engagement.

And among other, non-financial targets, RBS is still struggling to win the trust of customers. That's particularly with Ulster Bank and the Royal Bank of Scotland brand now mainly confined to Scotland. NatWest seems to have avoided much of the toxic spill.

- Published24 February 2017