Rummaging in the basement

- Published

Hurricane Energy likes to make a bit of an impact. Why else name your oil prospects after RAF bombers and fighter aircraft?

Prospects are turning into finds, or what the industry likes to call "plays".

Hurricane now claims to have found more oil in the past 10 years in UK waters than any other company.

The secret to its success is not luck, but looking at rock formations where the others don't.

It's a reminder that this industry is one for niche players as well as the big majors, which are active extracting hydrocarbons from the Shiehallion and Foinaven fields not far from Hurricane's activities.

Robert Trice, chief executive of Hurricane from its Surrey base, has experience of working within the majors, and is now applying that to finding new reserves in untested geological formations.

Giant sponges

The jargon is "fractured basement reservoirs". No, they wish to emphasise, this is not about fracking.

This is about very hard rock, such as granite, or the Lewissian gneiss from which the Outer Hebrides are formed. And very old it is too - some of the oldest in the world.

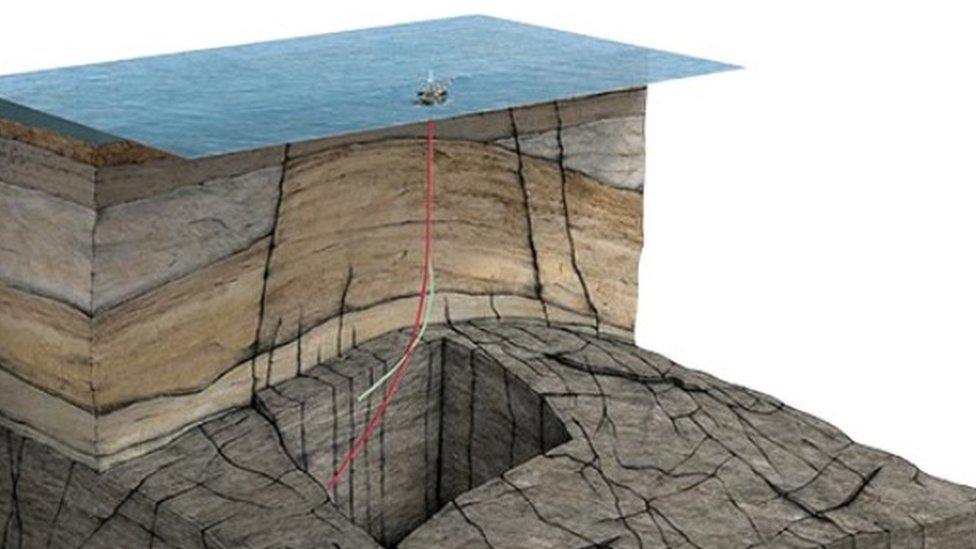

It isn't permeable like sedimentary or sandstone rock, from which much of the North Sea's oil and gas is extracted. That has the hydrocarbons trapped in porous rock. When geologists talk about reservoirs, they don't mean giant subsea pools but giant sponges.

However, Hurricane is going after oil and some gas that is trapped in the fissures created by movement in the rock. Seismic activity, such as earthquakes, over billions of years fractures rock, and oil and gas can fill the gaps created in those billions of tiny spaces.

Drill bit

The best prospects seem to be where there is an upsurge in rock, creating a ridge, in which hydrocarbons can be trapped. This provides the "basement" for the sandstones from which most hydrocarbons are extracted.

So in the case of the Hurricane Energy find in the Halifax prospect, west of Shetland, it drills in around 150m of Atlantic ocean, down more than 1000m beneath the seabed to reach the "closure" which tops the hard rock formation, and after that the drill bit continues for more than 1100m.

It is down that column of rock that it has found extensive fracturing. The company didn't have time or the budget to retain its drilling rig lease and extract much oil, but it did find the fractured geology looks promising for lots of oil to be trapped.

And because it looks so similar to the nearby Lancaster field, the geologists reckon they are looking at a single rock formation covering a large area.

Egypt to Vietnam

Just how big and how much oil is hard to tell. They're not giving numbers, and if they did, they'd have very wide margins of error.

The Lancaster discovery, first made in 2009 covers around 15km by 5km. It is estimated to have between 62 million and 456 million barrels of oil in it.

Before committing the funds to developing, these fields will require more appraisal. And without the comparisons that are more easily made with extensive experience in sedimentary rock, the estimates are trickier to make.

Drilling through granite and other hard rocks is tough. It requires new understanding of how drill bits and water behave.

There is some experience with fractured basement reservoirs from onshore South America to China, to offshore Egypt and Vietnam.

Hurricane and its boss, Dr Trice, reckon the seas around Scotland and Norway have "prolific" opportunities to explore similar rock formations.

Shore thing

Worth noting, on a closer commercial frontier, is the slippery stuff finding itself into a fast-widening range of cosmetics and foodstuffs.

I was served up a seaweed and lime salad dressing on Sunday, just as the Scottish government was about to set out its approach to regulating the seaweed industry. (A lot more lime than seaweed was evident, but very nice it was.)

Seaweed holds a lot of potential, and could be an important source of biofuels. Its advantage over land-based biofuels is that it doesn't displace other food production. Not yet, anyway. It depends how popular that salad dressing becomes.

Seaweed farms can operate on the same basis as mussel beds, in long strands. The Scottish government is all for small to medium-scale seaweed farms, on certain conditions.

It isn't encouraging large-scale cultivation - not without an understanding of the potential impact of algal blooms, collision risks and other coastal impact.

The conditions are mainly about location. Seaweed should only be harvested away from sewage outflows. It is not known, yet, how well aquatic plants handle nasty toxins. So it is best to locate it in waters where shellfish are already harvested and monitored.

Commercial exploitation of seaweed is nothing new. Kelp was big business in the Hebrides and Orkney in the 18th century, in the supply chain for chemical and soap manufacturing.

That was until changed trading relations with Europe brought cheaper imports. Sounds familiar?

- Published28 March 2017