The pensioner who was a Bridge of Spies cold warrior

- Published

Frank Meehan has retired to Helensburgh on the west coast of Scotland after years as a Cold War diplomat

If you ran into Frank Meehan strolling along the banks of the Clyde estuary near his home in Helensburgh, you wouldn't notice much that was remarkable about him. He looks like any other pensioner enjoying a peaceful retirement.

But, now in his 10th decade, Frank can look back on a life spent at the heart of some of the most dramatic moments in the 40-year nuclear stand-off between the Soviet Union and the West.

Frank grew up in Clydebank, a town about eight miles west of Glasgow, famous for shipbuilding.

But he spent four decades as a US diplomat living, almost exclusively, behind the Iron Curtain in Communist Eastern Europe.

Frank was born in the US but grew up in Clydebank

As a teenager he survived the Clydebank Blitz, an aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe during World War Two, which killed 500 and destroyed thousands of homes.

"There was a bad attack on the shipyards in March 1941," he told me.

"I was 17. We were in a shelter and the bombing started quite far away but you could hear them getting closer. The house next door got incendiary bombed and was destroyed.

"I worked clearing the rubble of houses that had been burned. I carried a bricklayer's hod. I was not much good at that. Maybe that's what made me think of the Foreign Service".

The event that changed the course of his life was his call-up.

Frank had been born, in 1924, in the United States, during a brief period when his Scottish parents were living there.

This made him a US citizen, and in 1945 he was drafted for military service. As a young GI he was posted to occupied Germany.

Frank Meehan joined the US State Department as a diplomat after the war

Frank had a degree from Glasgow University and was already a fluent German speaker.

On a whim, he applied to join the US State Department as a diplomat - and got in. He became fascinated by Russia.

"I think once you get the Russia bug you never lose it," he said.

"It's the unknown that lures you when you're young, you know?

"I just thought 'what is this world?'

"'Who are these people who had almost collapsed under German attack and then fought their way from Stalingrad to Berlin?' I wanted to understand."

So Frank learned Russian too - and it became a lifelong passion.

He was based at the Moscow embassy in 1960 when Soviet forces shot down a top secret US spy plane and captured its pilot Gary Powers.

The U2 high flying spy plane developed by America

The US officially denied the existence of the so-called U2 spy programme. But the Soviets now had the proof.

Powers was put on trial and given a long prison sentence. The wreck of his plane was put on public display.

Frank was despatched by the US ambassador to go and take a look.

"I was pretty tense," he said.

The remains of the U2 spy plane flown by American pilot Gary Powers, which was shot down over Soviet airspace

"I thought there might be some kind of manufactured incident. But I went to the head of the long line of people waiting to view it and the Russian guard looked at my pass and grinned and said, in Russian, 'Be my guest! It's your plane after all!'"

Two years later, Frank was back in Berlin.

Moscow had offered to swap Gary Powers for a Soviet agent called Rudolf Abel, who'd been caught spying in Brooklyn.

Gary Powers, accused of espionage over Russia in his U2 airplane, on trial in Moscow

They asked for the release of a young American student called Frederic Pryor as part of the deal.

Pryor had been studying in East Germany and had been arrested by the Communist regime there and accused of espionage. Pryor now became Frank's responsibility.

This is the incident that was dramatised by Steven Spielberg in the 2015 film Bridge of Spies, starring Tom Hanks and Mark Rylance, as Abel.

"The swap [of Powers and Abel] was to take place on Glienicke Bridge," said Frank.

Frederic Pryor would be handed over at Checkpoint Charlie in the centre of Berlin.

"There were tense moments obviously," Frank said.

"When I was walking over [into East Berlin], I didn't know how the kid, Frederic Pryor, would be.

The Glienicke bridge in Berlin after US pilot Gary Francis Powers was swapped for Soviet spy Rudolf Abel in 1962

"He'd been in prison. I didn't know whether he'd be well, whether we'd get him out, whether I would be able to get out myself."

Frank found Pryor sitting in a car with an East German intelligence agent called Wolfgang Vogel, whom Frank knew. The two would become lifelong friends.

Frank recalls: "Vogel said 'Frank we're not ready. Get in the car and wait'.

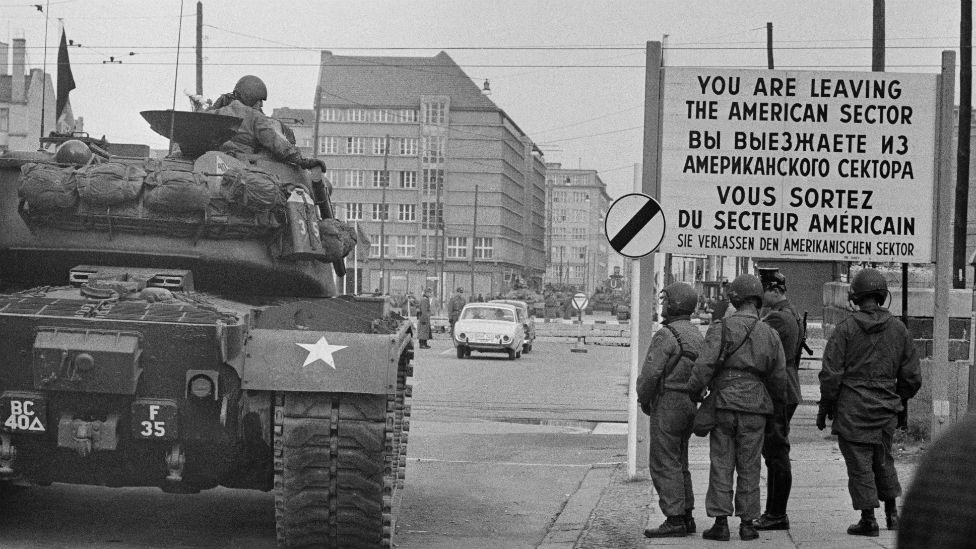

American tanks and troops at Checkpoint Charlie, a crossing point in the Berlin Wall

"He was waiting for word from the bridge that the Powers-Abel swap had taken place.

"We were in the car waiting. I was getting more and more nervous.

"The car was surrounded by a group of East German goons, security people.

"Eventually one of them came over to me and said 'It's OK'. And Vogel said 'Frank - you can go'."

Frank walked Frederic Pryor the few dozen yards that separated east from west Berlin - and from captivity to freedom.

Had he seen the film, Bridge of Spies?, I asked.

"Oh yes it's very good. As you'd expect."

Is it accurate? A wry diplomatic smile. "Oh yes. Mostly."

Frank became US ambassador in Czechoslovakia and then, in 1980, in Poland.

Friends and relatives of striking workers listen to the news given by Lech Walesa outside the gates of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk

His arrival in Warsaw coincided with the birth of Solidarity, the democracy movement that had emerged from protests and strikes by workers at the Gdansk shipyard.

The movement's leader, a shipyard electrician called Lech Walesa would become one of the great figures of 20th Century European history. In the early 80s he was a dinner guest at Frank Meehan's table.

Frank said: "Walesa was very smart. Politically very clever. Moderate, too, and careful.

"He had to deal with militants in his own movement and he had to try to control them so that they didn't push things too far too quickly. He was very good at that. I was impressed."

Lech Walesa, leader of the Polish trade union, Solidarity, on strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in 1980

Luck wasn't on Frank's side. He was on a working visit to Washington DC when, in the winter of 1981, the Polish Army declared martial law and seized power.

Frank's bosses at the State Department wanted him back in Warsaw immediately. But the coup leaders had sealed the borders.

He laughs about it now but at the time it was no laughing matter.

"If there's going to be a revolution in Eastern Europe and you're the ambassador, you'd better be in the country," he said.

"I was told to get back in quickly.

"I flew to Berlin and travelled overland to the East German-Polish border. The embassy sent a van for me. Travelling back [after the coup] was sad. Everything had changed."

Polish General Jaruzelski who declared martial law as Secretary of the Communist Party to crush the Solidarity movement

We look back now and see that moment as the beginning of the end for Communism in Europe. But it didn't seem so to those who, like Frank, lived through it.

He said: "It's one of the great mysteries as I look back on it and on my own work.

"I still have difficulty understanding exactly what happened to the Russians - why they decided to pack in and leave Eastern Europe. It's to me an inexplicable decision".

But it's a decision that still shapes our world.

Frank Meehan is as engaged now with world affairs as he ever was. He has never shaken off his Russia bug.

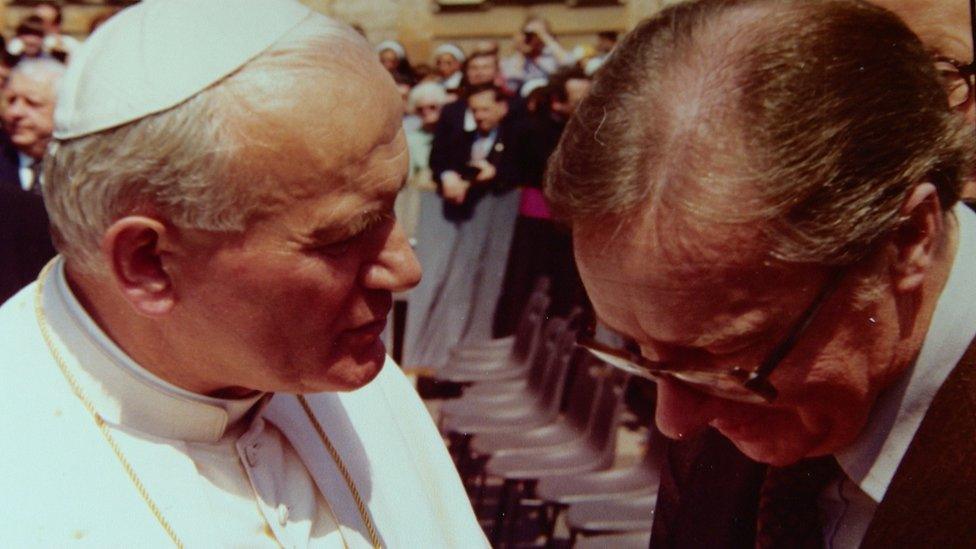

Frank met Pope John Paul II in his role as a US ambassador

"What strikes me about Russia today is the tremendous sense of loss they have - of power and position," he said.

"That explains Putin's hold over them. But Putin can't last forever. The more I look at Russia today the more I'm reminded of the last days of the Czars, Russia between 1900 and 1917."

And I asked him about his unusual dual identity.

Does he feel Scottish or American?

"Oh no I'm an American. I love Scotland and I came back to retire here because it's what my wife wanted."

His wife Margaret died two years ago.

He told me: "When we came here, we worked out that this was our 23rd home since we were married.

"When you've dragged your wife around Eastern Europe for all that time, you owe her something.

"But I miss America. I'd love to be in Washington now watching what's going on there up close."

Scotland's Cold Warrior will be shown on BBC One Scotland on Monday 3 April at 19:30.