It's not the economy, stupid - is it?

- Published

How much will the economy feature in this election?

The Westminster election on 8 June will be about lots of things. They always are. But as a national debate, my hunch is that it is likely to be mainly focused on Brexit and who gets to occupy 10 Downing Street.

The wisdom of James Carvel, the Ragin' Cajun' strategist for Bill Clinton back in 1992, was that the electoral battleground "is the economy, stupid". And so it goes in most campaigns.

But the economy seems less likely to be decisive this time. For most of Britain, it's not doing that badly, particularly the jobs market. But inflation is rising.

And in Scotland, growth has stalled. The economy may even have been in recession this winter. It could be more of an issue in Scotland, if the political parties wish to prioritise it.

For a UK election, though, the economy looks more likely to feature in the context of these two dominant themes; what will Brexit mean for the economy, and what are Jeremy Corbyn's economic priorities?

Corbynomics

The Labour leader has begun the campaign with a statement that makes no mention of Brexit.

It would be astonishing if he is allowed to keep it that way. His preference will be to talk about the economy and the workplace. His opponents will also want to talk about his plans, but in very much less positive terms. (My additional hunch is that the Daily Mail and The Sun are about to draw on every one of the dark arts in targeting the Labour leader. It won't be pretty.)

The Labour programme, so far, includes a big boost to public spending and setting up a national and regional public investment banks. It wants labour market reforms, worker protection, stronger trade union rights, and a £10 minimum wage, with "in-sourcing" of public services and transport from the private sector.

Phillip Hammond wanted to raise National Insurance for self-employed workers

The Corbyn programme calls for house-building and protection of tenancy rights. (Only some of these would apply north of the Border.)

Corbyn's opponents will either target his past record of backing for controversial causes, or his future plans. The last two Tory campaigns have pitted Conservative deficit-reduction plans against Labour's.

We can now see that there wasn't that much difference between them. Since the last Westminster election, and post-Brexit referendum, the Tories have all but adopted a profile for delaying deficit reduction that is similar to both Labour's and the SNP's in the 2015 campaign.

But against a Corbyn leadership, there will surely more difference between the two candidates for Prime Minister. Both sides will want to emphasise that.

Fewer constraints

What, then, of the Conservatives? Theresa May wants a mandate for her Brexit negotiations. She wants a bigger majority. Her opponents say that's an opportunity to harden the Brexit process.

But as Simon Jack explains, the markets are among those interpreting it as a means to soften it - to face down hardliners in her own party.

A fresh May manifesto could also give her a mandate for other items on her agenda. Take National Insurance, for instance. Phillip Hammond wanted to raise that for self-employed workers, but had to execute an abrupt and humiliating U-turn when his own party revolted against such a blatant breach of David Cameron's 2015 manifesto.

The promise not to increase rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT could be weakened by 8 June.

Likewise the triple lock on pensions - a promise to raise the state pension to whichever is highest from price inflation, average pay or 2.5%. To Phillip Hammond and to most demographers, that looks expensive, and he indicated that he wanted to revisit it for the next manifesto. He was assuming at the time that he was talking about 2020.(That budget, in hindsight, must go down as the least election-oriented in modern times.)

The House of Commons will formally hear the request for 8 June election

It's reported that Theresa May was not enthusiastic about the detail put into the 2015 Conservative manifesto. She may wish to constrain herself less, and she may have the opportunity to do so.

The opinion polls suggest that the Conservatives have room for manoeuvre. They don't face the same Europhobic threat from UKIP as in 2015. And they don't face a threat from Labour in the centre ground.

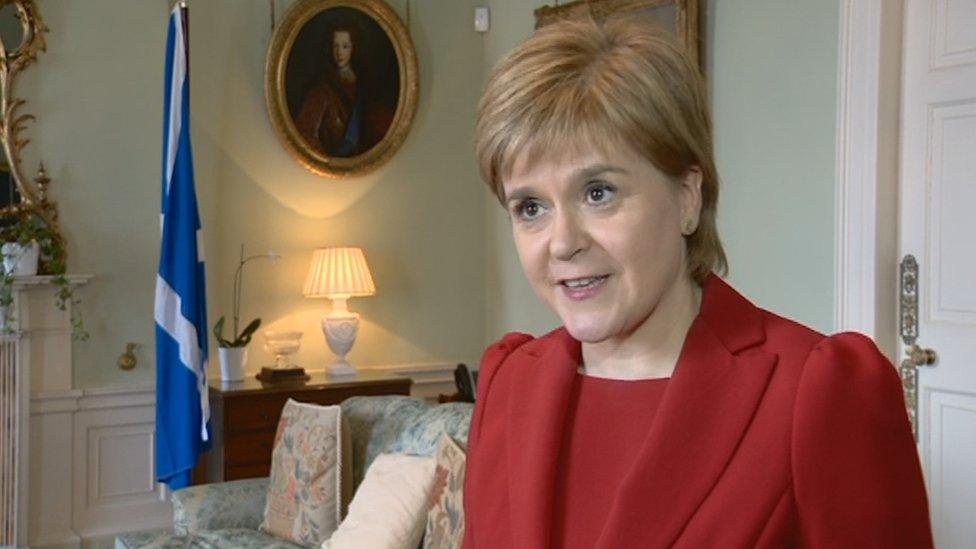

In Scotland, they can hope voters will send more than David Mundell to Westminster. They are claiming some momentum from last year's Holyrood result.

Could Theresa May offer further devolution of financial powers to deflect debate away from the SNP's pressure for a second independence referendum?

We now know Mrs May is more of a gambler than she seemed. Let's see if she's also willing to gamble with the economic chapter of the manifesto.

- Published18 April 2017

- Published18 April 2017