The Purpose: SNP’s economic record at 10 years

- Published

The SNP has now been in power for 10 years

It was Friday 4 May 2007, at 5.20pm, when the Scottish parliamentary result for the Highlands and Islands result was finalised. David Thompson filled the last vacant seat. The SNP had one more MSP than Labour.

On that tiny margin, Alex Salmond built a minority administration. Ten years later, and now dominant in Scottish politics, how does the Scottish National Party's economic record look?

I've been asking that question for a forthcoming book of essays: 'The Nation Changed? The SNP and Scotland 10 Years On'. This is a shortened version.

For eight years of a new devolved parliament, the economy had been a problem for the Scottish National Party.

Without government experience, the party was perceived as untested and risky. Little of the business community was on board. And the economy was changing. Scotland had moved on from a narrative of post-industrial collapse.

The economy's relatively strong performance required a shift in SNP strategy. No longer could the party claim that Scotland was being left the poor relation.

Alex Salmond pictured not long after the 2007 election

The immediate challenges were easily overcome by changing the mood music. The SNP had turned positive. If the economy could no longer be portrayed as being kept behind the UK by Westminster decision-making, it could be portrayed as failing to reach its potential for doing better than the UK.

Salmond talked of an "arc of prosperity" in which smaller countries, from Ireland to Iceland to Norway, were storming ahead confidently on strong growth rates.

The party choreographed a series of big name endorsements during the 2007 campaign. Most notable was Sir George Mathewson, architect of what was then the rampant Royal Bank of Scotland.

Less high-profile, but influential in winning corporate hearts and minds, were the energetic efforts of Jim Mather and Andrew Wilson - a successful businessman and inspirational salesman, along with a smart economist.

They took a PowerPoint roadshow around any business audience that would watch it. They emphasised the opportunities for cutting corporation tax, to emulate Ireland's Celtic Tiger.

Alex Salmond vented his anger at the closure of a Diageo bottling plant

In retrospect, we know the economy was about to enter recession as the SNP took power. And the intentions of boosting the growth rate, to join the Celtic Tiger in Ireland, were about to be overwhelmed by the financial crisis. Scotland's two banking giants required a massive government bail-out.

The Salmond administration put in place policies that could help support the economy through the crisis. Where it could boost infrastructure spending, it did, shifting some funds from revenue spending.

The new government was focused around its objectives, and above all, with a capital P, was the Purpose of growing the economy.

'Soften the blows'

A dominant narrative for the SNP administration was the benchmarking of Scotland's performance against the UK as a whole.

While ministers sought to highlight difference, through much of the downturn, Scotland was more like the UK average than any other part of Britain, particularly and ironically the outlier that is London.

When it looked better, there was credit to be taken. When it looked worse, Westminster's austerity measures got the blame.

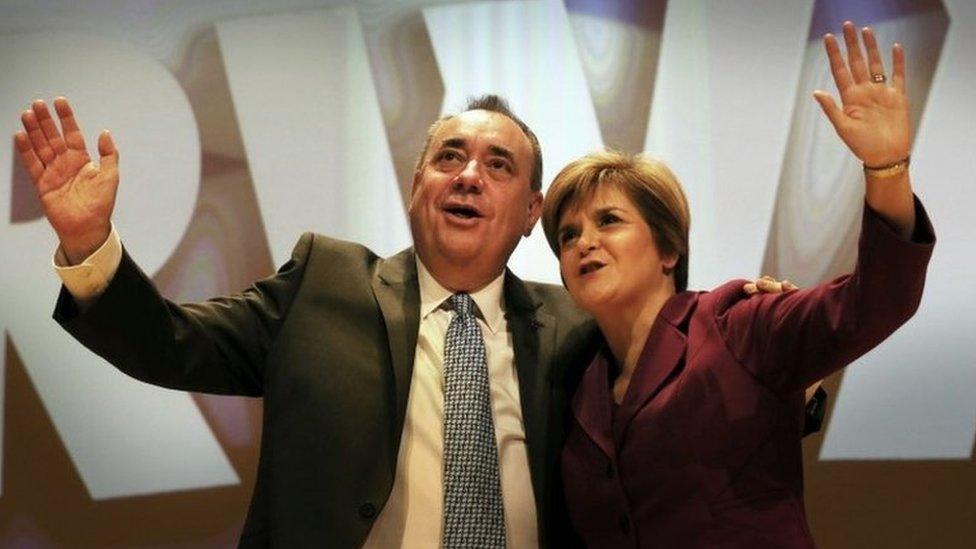

Nicola Sturgeon is said to have a different approach to Alex Salmond

With economic events beyond its control, the priority was to have a plan, to look competent and to look busy. It helped that the economy was the subject that most absorbed the first minister's attention.

Those around him say he typically took a broad brush to policies around public services, or simply delegated. But he had a sharp focus on getting his economic policy right. The same people note that Nicola Sturgeon has the reverse approach.

Important to this was talking positively about the "re-industrialisation of Scotland", building on its potential in renewable energy. Scotland could be "the Saudi Arabia of renewable power", including wind, tidal, wave and CCS - carbon capture and storage.

Oil price plunge

Policy also sought to soften the blows from plant closures. The public spending on infrastructure - motorway upgrades, the Queensferry Crossing, the Borders railway - delivered an improbably large boost to construction sector statistics.

The food and drink sector had a strong showing, and tourism handled the downturn with flexibility. Scotland retained a relatively strong rating as a destination for inward investors.

Notable episodes that worked less well start with Diageo and its Kilmarnock bottling plant, where the first minister vented his anger at its closure - a campaign doomed to failure that exposed the tensions of a government leader in opposition mode, and alienating one of the country's biggest inward investors.

The drop in the price of oil was a challenge for the Scottish government

A significant shift in economic policy with the arrival of the Salmond administration was a shake-up for Scottish Enterprise.

It was stripped of much of its established role, and under Jim Mather as enterprise minister, it was re-oriented to backing only the companies with high-growth potential - at first, around 2000 of them.

This took it out of the political football arena, at least until 2016. Newly appointed as economy and work secretary, Keith Brown was then given the task of finding an answer to the country's sluggish rate of economic growth. He set about the enterprise agencies.

The solution remains a work in progress.

Through much of the decade, the oil and gas sector provided a bulwark against volatility and a shortage of confidence elsewhere.

Brexit referendum

But just as the rest of the economy was getting back to a more stable performance, the oil price tanked. It is the best explanation for a sharp divergence in the performance of the Scottish economy from that of the UK as a whole.

This was both an economic and a political challenge for the Scottish government, with the depth of the plunge only becoming clear in the wake of the 2014 referendum.

That campaign had "baked" high oil revenues into the optimistic public finance forecasts. But with the oil price plunge, the chances of a tax bonanza to fund Scottish public services, to plug the deficit and to build up a Norwegian-style national wealth fund, had to be re-thought.

With independence and control being debated, it was not until the Brexit referendum that issues of economic nationalism arose, but it came from England.

Alex Salmond had sought to defend ScottishPower against a Spanish takeover while he was in opposition. But in his first day in government, he went to Longannet power station to meet Iberdrola's chairman, Ignacio Galan, and the issue of protecting strategic corporate assets never arose again.

It's tempting to draw conclusions about 10 years. But this is only a milestone. So what can be said about the story so far?

One is that the initial challenge of establishing a reputation for competence and working with the business community was a quick victory. The party's opponents will tell a different story, but they struggle to match the SNP for that reputation now.

The test the administration set itself of making economic growth its single, unifying Purpose, with that capital P, has not been as clear a success.

That is partly because Scotland had already reached the SNP's growth target of matching the UK level, before the SNP took office.

Such plans were swept aside by recession and the global financial crisis. Over 10 years, the Fraser of Allander Institute notes that growth of GDP has averaged only 0.7% per year, and growth of GDP per head has averaged only 0.2%.

With four more years of this parliament and hopes to hold office for much longer, the SNP can maintain its active and pragmatic approach to economic management.

It has recently gained new powers over income tax, which explicitly link economic growth to the amount of funds available for public spending. That makes the economic choices harder and sharper. Economic developments have rendered the case for independence tougher to make.

Meanwhile, other economic pressures continue, or are closing in: the productivity puzzle, expectations that inequalities can be reduced, political pressures against globalisation, the robotics challenge to employment, the decline of offshore oil, the shortage of housing, skills shortages if EU workers are excluded, and the financial questions of how to adapt public services to demographic change.

There's plenty still to be done.

A Nation Changed? The SNP and Scotland Ten Years On, edited by Gerry Hassan and Simon Barrow, is to be published Luath Press in June.