Illegal to be gay - Scotland's history

- Published

Gay Pride Edinburgh 2016

Scotland prides itself on being one of the most progressive countries in Europe on issues of sexuality and gender identity but for gay men it was not always such an open-minded place.

Homosexuality among men was illegal in Scotland until 1980.

Same-sex contact between women had never been targeted in law and was not illegal. Scottish society just chose to believe lassies did not do that kind of thing.

When the Sexual Offences Act was granted royal assent on 27 July 1967 it applied to England and Wales only, Scotland, along with Northern Ireland, was excluded.

England and Wales can now mark 50 years since the historic reforms which partially decriminalised homosexuality between two consenting men in private over 21 years of age.

But Scotland took 13 years to adopt the same legislation into Scots Law.

Why did it take so long and what effect did it have on the men who lived through that period?

Nick and Phil's story

"Making a law that says that something is legal doesn't necessarily change attitudes"

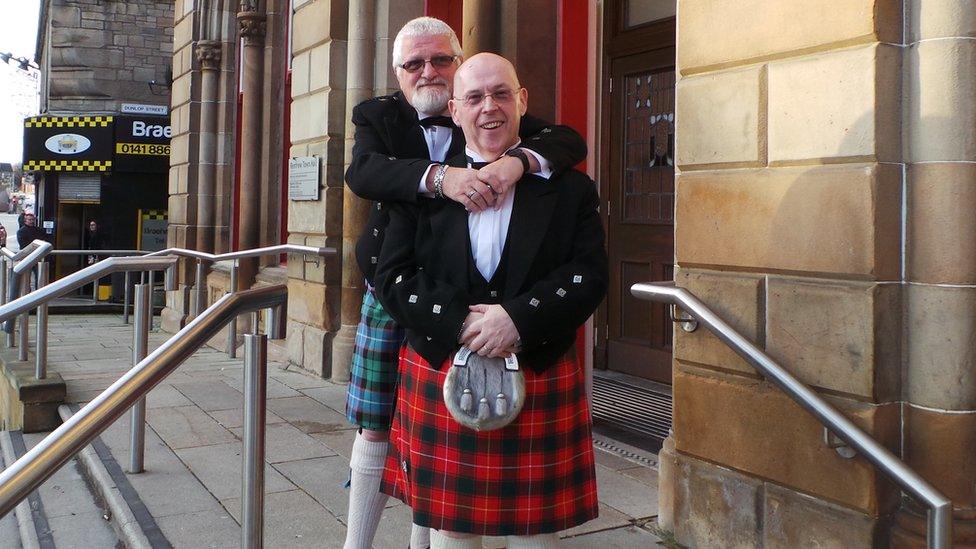

Nick Mitchell and Phil Duffy converted their civil partnership to marriage on the first day it was allowed by law, 16 December 2014. So they believe they are the longest-married gay couple in Scotland.

Nick, 71, grew up in England and moved to Scotland to be with his partner Phil, 64, in the early 2000s. Both men were secondary school teachers and struggled to reconcile their public and private lives.

"In the 90s and in the 80s, I could be quite aggressive, quite angry, quite frustrated," recalls Phil.

"I think I suffered a kind of trauma. Even though the law changed in Scotland in 1980, I was getting messages 'you're wrong, you're diseased, you're this, you're that'.

"So I shut my mouth. And suppressing all that, natural urges and so on, does have an effect on you."

Nick (left) and Phil (right) converted their civil partnership to marriage in 2014

Phil adds: "Making a law that says that something is legal doesn't necessarily change attitudes.

"So when the law changed in 1967 in England and Wales, and in 1980 in Scotland that didn't necessarily make it any different.

"I don't think it actually came into my conscious mind that the law made it legal to be gay or homosexual.

"And when I eventually came out, when I met Nick, and I had to tell family and friends, I was amazed with the reaction.

"'It's about time you told us', 'What were you worrying about?'

"If I had been told that message, or the opportunity had been there for that message to be given to me earlier, then I wouldn't have suffered all those years."

Aversion therapy

Nick talks about moving to London in his younger days where he was raped by another man.

The episode left him shaken and seeking answers. Voluntarily, he sought medical treatment to address his sexual attraction towards men.

"I was an in-patient for two weeks in what I assume was the mental ward. I sat in the chair and there was a projector behind me and fixed to the left arm of the chair was a button.

"The rules were quite simple. If a picture of a woman came up on the screen then I knew I wouldn't get an electric shock.

"If a picture of a man came up on the screen, and I pushed a button, I might not get an electric shock.

"But if I just sat there and looked at him I knew my arms would be flung up in the air. The pain was pretty excruciating.

"I'm very sad about it. I can feel myself, sort of..."

At this point in the interview Nick pauses to fight back the urge to cry.

He continues: "It's just so cruel."

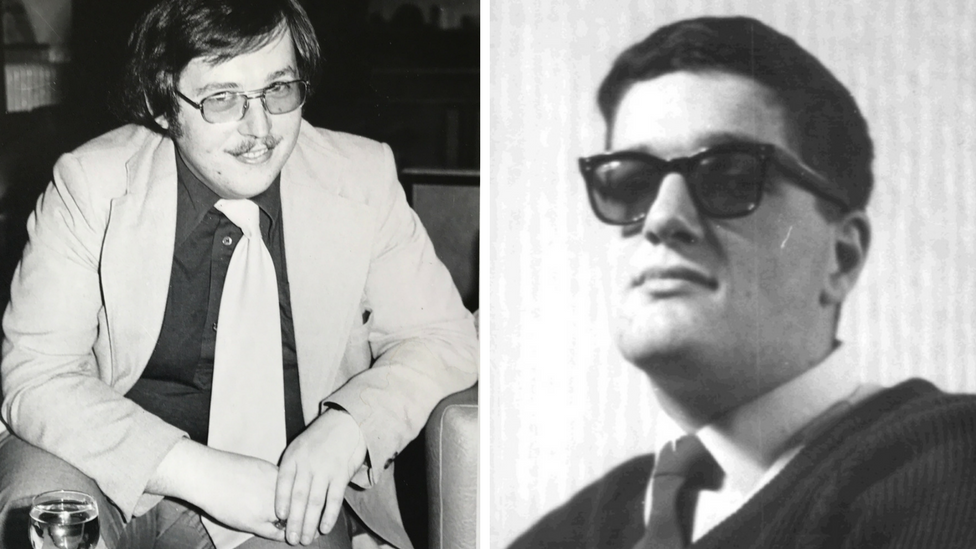

Phil (left) in the 1980s and Nick (right) 1960s

Police entrapment

Witness testimonies of the period also tell stories of police entrapment.

Nick explains his brush with the law.

He says: "I was so frustrated and lonely and isolated and all those things that single people go through, and more so when you feel you're outside of society, that I did what many gay men have done and that is I used to use toilets to try to find some sort of contact.

"One day I was trapped by the police, which was a normal procedure for the police. I was arrested. I could have died, I didn't know how to cope with it. Ended up in court - I tried to lie my way out of it and failed totally. I was so naive. And I was fined.

"There was nobody I could talk to, there was nobody I could share it with either, how I felt beforehand or afterwards having gone through court and been condemned and that went on for years, because every time I would go for a post, especially here in Scotland, I would have to fill in one of these forms to have my record checked."

Stories like Nick and Phil's are familiar ones for gay men who grew up in 20th Century post-war Britain. A great deal of fear and hostility was directed towards gay people.

After the war an increase in prosecutions for homosexual crimes in England and Wales drew the attention of government.

The Wolfenden Committee

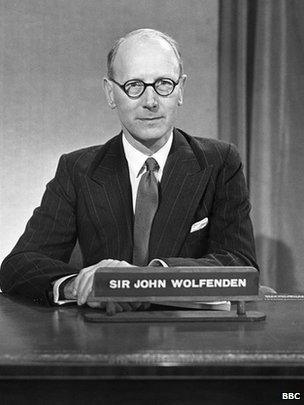

Sir John Wolfenden on the BBC in 1957

Sir John Wolfenden was asked by the Home Office to form a committee to advise on how laws around homosexuality might be reformed. The Wolfenden Committee commenced in 1954. Religious groups, legal representatives from the home nations, civic leaders and legislators all gave evidence to the committee.

The Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution in Great Britain finally submitted its report in 1957.

It recommended that the criminalisation of homosexuality impinged civil liberties.

It in no way condoned or sanctioned same-sex relationships, or indeed same-sex sex.

Wolfenden's report recommended that homosexual sex was a private issue of personal morality.

It also advised that young people and vulnerable adults be protected from homosexual activity.

The report condoned the use of medical treatment for homosexual impulses and behaviour.

Cabinet did not take any of the recommendations of the report forward at the time.

However the work of the committee was a milestone moment in public discourse on homosexuality.

Ten years later Leo Abse MP sponsored reform to the Sexual Offences Act.

A free vote in the commons meant that eventually the recommendations of Wolfenden were enshrined in law in England and Wales.

However Scotland and Northern Ireland were exempt from the reform.

Scottish opposition

"There's a lot of resistance to Wolfenden in Scotland"

Dr Gayle Davis is a social historian from the University of Edinburgh. She co-authored a book on sexuality and Scottish governance through the period 1950 to 1980.

Dr Davis says that Scotland was exempt from the 1967 Sexual Offences Act for reasons grounded in the attitudes of Scottish civic society, the influence of the church and also the Scottish criminal justice system.

She says: "There's a lot of resistance to Wolfenden in Scotland, there's really a great deal.

"Law in fact can be quite resistant - lawyers themselves.

"And one of the reasons, kind of ironically, is because they argue Scotland has, basically, a more lenient legal system anyway.

"It's actually much more difficult to be prosecuted for homosexuality in Scotland than it is in England and Wales and therefore let's not touch it. we don't need to interfere."

Polls in the media

A Daily Record poll in 1957 indicated that 85% of Scots surveyed, opposed the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report.

Around the same period in 1957 a poll conducted by the Daily Mirror, south of the border, showed a much more even split where 51% opposed decriminalising homosexuality.

Dr Davis adds: "Then also it's seen as, well we know Scottish people just don't approve of homosexuality, that's what the churches keep telling us.

"That's what these polls, when they're occasionally taken, do seem to tell us.

"So there's also a strong sense that, whether or not gay people are being apprehended, that actually we fundamentally don't want to publicly state that it's acceptable."

During her research Dr Davis learned about some of the therapies being used to treat gay men convicted of homosexual crimes.

The treatments - which convicted men had to consent to - included chemical castration or oestrogen therapy.

The controversial treatment, often attributed to the infamous suicide of World War Two code-breaker Alan Turing, was sanctioned in Scotland.

She says: "In some places electroconvulsive therapy was used, ECT.

"My understanding it was not used in the Scottish prison system.

"But it could be used in homosexual cases and it certainly has been used in the past.

"One of the interesting ones in Scotland is oestrogen therapy and it's interesting because it wasn't seen as legal in England and Wales.

"And actually Wolfenden mentions this, that maybe it should be, or could be used, in other areas. But in Scotland it is being used in the Scottish prison system."

James Adair - voice of dissent

A Scottish voice who opposed decriminalisation of homosexuality in Scotland was James Adair OBE, a former Procurator Fiscal of Glasgow and Edinburgh.

He sat on the Wolfenden committee and formed the only dissenting voice. His minority report was printed in the Scotsman on 5 September 1957.

Mr Adair was quoted as saying: "The presence in a district of, for example, adult male lovers living openly and notoriously under the approval of the law is bound to have a regrettable and pernicious effect on the young people of the community".

In the Glasgow Herald of 27 May 1959 Adair was reported as having addressed The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland as a commissioner from the Presbytery of Glasgow.

He urged the assembly to disapprove of what was suggested by the Wolfenden committee regarding any amendment to the law in Scotland.

Adair advised that any legal changes would make "sinning for the sake of sinning" no longer unlawful.

The Assembly's firm opposition warned that legislation which sought to legitimise homosexuality would only increase "this grave evil".

21st Century Scotland

Marching at Edinburgh's gay pride parade in 2016

Dr Davis says that, MPs such as Robin Cook were influential in motivating change in Scotland through the 1970s and 1980s.

It was also thanks to the work of pressure groups like, the Scottish Minorities Group, external, who took a case to the European Court of Human Rights, which led to Scottish law finally levelling with that of England and Wales through the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980.

Much has changed in Scotland.

The practices and views of the past seem unrecognisable today.

However it is an uncomfortable fact that Scotland did lag behind other parts of the UK quite substantially on its legal position on homosexuality - a stance which the Scottish government now describes as discrimination.

A spokesperson from the Scottish government's justice division says: "Until relatively recently, the criminal law in Scotland discriminated against same-sex sexual activity between men. Such laws clearly have no place in a modern and inclusive Scotland."

Police Scotland are in the top twenty of Stonewall's equalities index and march regularly in gay pride events in Scotland

The Scottish government has plans to introduce a scheme which would allow some gay men to have historical convictions, no longer considered illegal, to be removed from criminal records. This scheme is expected to be available this year.

The government's statement continues: "The justice secretary announced in October 2016 that the Scottish government will introduce legislation to provide an automatic pardon to people who have been convicted of offences for same-sex sexual activity that would now be legal.

"We will also establish a scheme that will allow men who were convicted as a result of actions that are now legal to have those convictions disregarded and have them removed from central conviction records. In these instances a person will be treated as not having been convicted of that offence.

"Scotland is now widely recognised as one of the most progressive countries in Europe on LGBTI rights. This summer, we are focussing particularly on making progress for transgender and intersex people by reviewing and reforming gender recognition law so it is in line with international best practice."

Progress still to be made

A Stonewall T-shirt worn at Glasgow Pride 2014

Stonewall Scotland, external campaigns for equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people. In a statement it says that although significant progress has been made, there is still room for improvement in some areas.

It says: "It's important to remember how far LGBT rights have come for LGBT people across Britain since partial decriminalisation in England and Wales in 1967.

"We've seen anti-LGBT laws repealed and laws which protect the LGBT community introduced. However, we must also use this time to think about the challenges that still lie ahead.

"While LGBT people might almost be equal in law, lesbian, gay, bi and trans people continue to face discrimination.

"LGBT people can find themselves excluded, or face verbal and physical abuse, whether at work, at school, in sport, in faith or within local communities.

"Trans people are disproportionately affected by discrimination and abuse.

"Overseas, same-sex relations are illegal in 72 countries, and punishable by death in eight.

"We all have a part to play in ensuring all LGBT people are accepted without exception and all we can hope is that, in 50 more years, we will have lots more progress to look back on."

- Published28 November 2015