Partition of India: 'They would have slaughtered us'

- Published

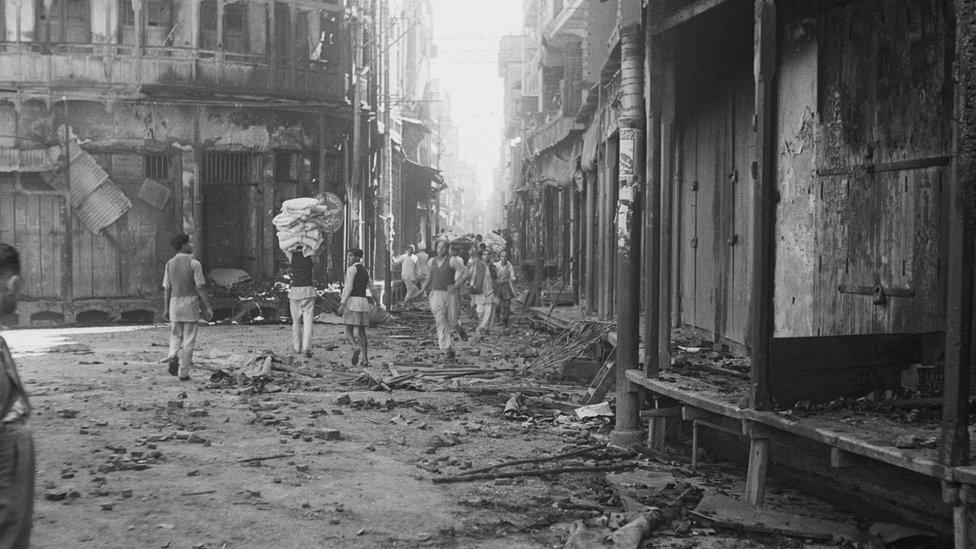

Indian soldiers walking through the debris of a building in Amristar in August 1947

When India was partitioned into two separate states in August 1947, the border between Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan was kept secret until the very last minute.

The Punjab was split down the middle and many people did not if they would be living in Pakistan or India.

The decision of the man drawing the line was not just an administrative formality, it was a matter of life and death.

One million died and 15 million were displaced as Muslims fled to Pakistan, and Hindus and Sikhs headed in the opposite direction.

Among those waiting to see if they would be on the right side of the boundary was Parduman Kohli, father of Still Game and River City actor Sanjeev Kohli.

Wrecked buildings after communal riots in Amritsar in 1947

Mr Kohli, who is now 83, was a 13-year-old Sikh living in Ferozepur in the Eastern Punjab, when he heard on the radio that India would be divided.

He says the idea of partition "sounded crazy".

"We lived together. I didn't see any reason for the partition," he says.

He was lucky that his town was put in India because if it had not, he says: "I could have been dead".

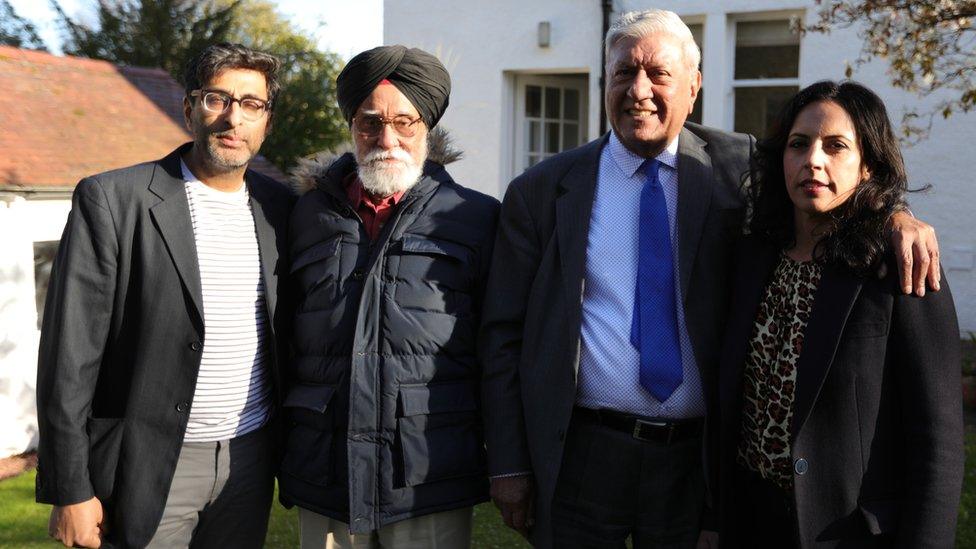

Sanjeev Kohli (left) and Aasmah Mir (right) found out about partition from their parents, Parduman Kohli and Arif Mir

Meanwhile, as a Muslim, Arif Mir, father of BBC Radio Four Saturday Live presenter Aasmah Mir, was equally fortunate that Raiwind, in western Punjab, became part of the new state of Pakistan.

He says: "We were scared but I think we were very naive. We didn't know what was in store.

"If Raiwind had been in India we would have been slaughtered because we were on our own, the police never came to help."

Mr Mir and Mr Kohli both experienced the chaos of partition and years later they ended up living and raising a family in Scotland.

Their Glaswegian children have been brought knowing very little about the turbulent events of 1947.

Still Game star Sanjeev with his father Parduman

For the BBC Scotland documentary, Partition: The Legacy of the Line, Sanjeev Kholi and Aasmah Mir spoke to their parents and other Indian and Pakistani people in Scotland who lived through one of the biggest upheavals in the history of mankind.

In August 1947, after almost 200 years, British rule was coming to an end, something many Indians, most notably Ghandi, had spent years campaigning for.

Britain had originally set a date of June 1948 for transferring power to an independent India but the potential for increased violence led the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, to bring the date forward.

Sanjeev Kohli and Aasmah Mir both have parents who lived through partition

Under pressure to reach a deal nationalist leaders including Nehru, on behalf of the Hindu Congress, and Jinnah, representing the Muslim League, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines - in opposition to the views of Gandhi, who wanted the country to be united.

The line deciding the new countries was drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe and, to avoid disputes and delays, it was done in secret and not published until two days after the actual partition had occurred.

Mohindra Dhall says: 'Our friends were butchered'

This led to increased panic and confusion as people tried to work out if they would be in the right country.

76-year-old Mohindra Dhall's family lived in Layallpur (now Faisalabad), which was on the Pakistan side of the border.

Although they were Hindus, they wanted to stay there, but reports of lootings and killings in the nearby villages forced them to leave.

Mr Dhall says they had just a few hours to pack up and leave.

They tried to get on a train to India but it was too crowded, with people on the roof and anywhere else they could find the tiniest space.

He says: "My father decided to come out of the train and we stayed back, only to hear the next day that whole train was completely butchered.

"Half of our friends from the village, who were on the train, got butchered."

Dr Salim Ahmed was also using the train but travelling in the opposite direction.

Dr Ahmed, who now lives in Paisley, was a 22-year-old medical student and he says he pretended to be a Christian, when he witnessed the horrific brutality being meted out on the railways.

"They came as a crowd," he says.

"They said 'Muslim, Muslim, Muslim' and they pulled them down from the train. They took the women and starting hitting them and started the massacre.

"The women were crying, 'my child, my child' but we couldn't help them.

"Little children, they took them and bang they killed them with a sword. They would just kill them on the ground."

Amrit Paul Kaushal recalls 'It was the first time I saw a killing'

Ghulam Malik Rabbani was a 12-year-old boy who found himself in a group of Muslim teenagers hell-bent on revenge after hearing rumours from across the border.

He says there were stories of Hindus killing and raping Muslim women.

According to Mr Rabbani, his 18-year-old brother was told to kill an old woman who was holding her baby grandson but he refused.

"That lady was killed by another person in front of us," he says.

In the peace of South Lanarkshire, 85-year-old Jaidev Hunna remembers the night he and his Hindu family left their home and took refuge with hundreds of others in a nearby college.

They thought they were safe until the arrival of the military, made up of Muslim soldiers.

Jaidev says: "We thought they had to protect us but at night they started shooting and killing all the Hindus.

"I was there and beside me were four or five bodies lying who had been shot and died.

"So I went in among the bodies and lied down, pretending that I am also dead. They came and checked the bodies and searched my pockets for money and then went away."

Reflecting now on the tumultuous events of 70 years ago Arif Mir, who is 82, admits that being part of such events as a 12-year-old had a lifelong effect.

He says: "When you are a young kid and you are frightened, it stays with you.

"The fright stays, the hatred stays, because it has been built into you. You will not trust one another because of the things that were done."

However, for Mr Kohli there was "badness" on both sides.

He says: "I still treat Pakistanis as my brothers. We grew up together, we lived together and I don't feel any animosity towards them."

Partition: Legacy of the line is on BBC Two Scotland on Sunday at 21:00.