'We spent almost two years sitting on a jury'

- Published

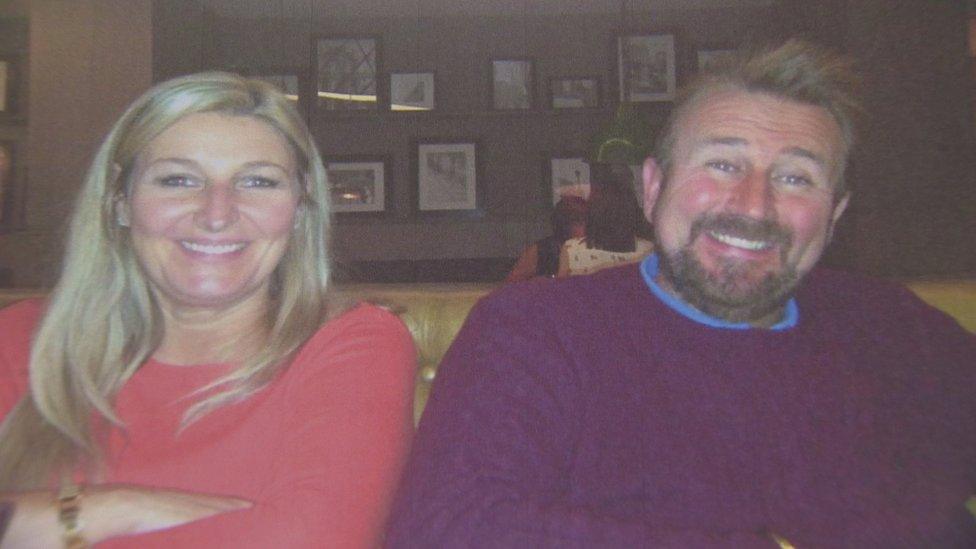

Paul, and his fellow jurors, Julie, Anne-Marie and Emma - who did not want to be fully identified - spoke to the BBC about their long spell in court

Two years ago, four ordinary people were brought together by a letter requiring them to report for jury service. They, and eight others, became the longest-serving jurors in UK criminal history.

The experience of sitting in silence for long periods and the responsibility of following a complex fraud trial has affected them all deeply and left some of them struggling to adapt to their normal lives.

However, the four agree that despite those struggles, they are glad to have sat on the jury.

It is rare for jurors to discuss their experiences and they are barred by law from talking about what went on in the jury room.

But Julie, Anne-Marie, Paul and Emma have agreed to talk about their 20 months in the courtroom.

In order to protect their identity, we are only using their first names and only Paul agreed to be photographed from the front.

What was the trial?

Edwin McLaren (right) with his wife Lorraine were charged with property fraud

The jurors first met when the trial of Edwin McLaren and his wife Lorraine for property fraud began at the High Court in Glasgow in September 2015.

It was a complex case with 29 charges and the jurors were told it would last up to six months.

When it finally finished on 16 May this year, the court had sat for 320 days over 20 months.

Guilty verdicts were returned on McLaren, who was said to be the brains behind the scheme, and he was jailed for 11 years. His wife Lorraine was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison.

The trial is thought to have cost about £7.5m.

Over its course, the jury was reduced from the original 15 for a Scottish criminal trial to 12, the lowest number it can operate on.

Julie - 'I'm not properly back at work yet'

The trial took place at the High Court in Glasgow

According to her fellow jurors, Julie was the liveliest in the initial stages.

But after nearly two years sitting on the jury, she has found it hard to slot back into her old life.

The 37-year-old returned to her job in a travel agency when the case finished, but quickly found herself struggling.

Julie says: "I went back and did two days training and then I went two days into the shop. I've never been back since. I've not given it up yet.

"I am going through the doctor and trying to get back into it. I'm still struggling. I just felt like I could not even hold a conversation."

Julie describes herself as a "people person" and says she got to know everybody at the court, including the lawyers and the admin staff.

The other jurors says she was the "cheeriest" of them all when they started out, but she now finds joining conversations difficult.

"You were sitting in a room listening to evidence but you didn't communicate. I'm really struggling with communication now."

Julie adds: "There should be more psychological support made available for jurors who sit through long trials.

"The judge did a great closing speech and he couldn't have thanked us any more but it was 'thank you and goodbye'," she says.

"That was hard, because we were like - 'what do we do now?'

"We've got the counselling number, but that also goes out to people who have sat on a jury for two days or a week.

"I just think that for that length of case there should be more support, with one-to-one counselling sessions, even before we left the court."

Paul - 'I thought it would never end'

"We got a letter at the start saying it was going to last six months," says Paul. "We didn't think it would go for that long."

But the complex trial and its many charges dragged on well past its expected finish date.

"I thought it was going to last forever," Paul says. "It just kept on going."

Paul, a 51-year-old civil servant, also says he has had trouble going back to work.

"I've had to be retrained," he says.

"I'm still not into the swing of things yet. I'm not talking much when I go to work.

"I think I was always talking before this trial, and now I am just sitting at my seat not really saying much."

For the first few weeks after the trial finished, Paul says he was surprised to find he missed it.

He found himself walking down to the High Court building in Glasgow and going into the nearby shops.

Despite his difficulties, Paul defends the principle of trial by jury.

"I think they should be tried by lay people - normal people - but I think 20 months is far too long for a trial," he says.

Emma - 'It gave me the chance to reflect on my life'

Emma worked in a fast food restaurant before she sat on the jury, and while she was away missed out on the chance of getting promoted to assistant manager.

However, since the trial finished the 26-year-old has decided to leave her job and take a different path.

She says: "While I was on the jury, I had time to reflect and I'm actually going to college now to study social sciences."

Emma says she suffered emotionally during the trial and was glad of the support from her fellow jurors.

She says: "I felt lost at times."

"We've been such a support to each other, we got each other through it."

Like Julie, she thinks there should have been more support offered.

"There was nothing there for us," she says.

"We couldn't speak to anybody about it. I think there should have been somebody there with us because of how long it was."

The length of the trial was almost unprecedented, but it was the fact that no-one had any idea how long it would last that had the worst effect.

"That was one of the problems for us all," Emma says.

"We couldn't look forward to it finishing because we never knew. We could never see the end of the tunnel."

Anne-Marie - 'If one needed the toilet we all went'

Anne-Marie, the oldest of the jurors to speak to the BBC, has also struggled with returning to her work as a civil servant after the trial.

The 57-year-old says: "I've worked in the same place for 40 years, but I feel as if it is alien to me."

Like all the others she feels the experience of having "our lives taken over for 20 months" has changed her.

She says: "It was a totally different way of life for 20 months, and then the day it finished you are back to what is supposed to be normal and it is difficult to adjust.

"Nobody realises the impact it has on everybody's lives."

For Anne-Marie, the hardest thing was no longer being part of a group of 12 who had spent so much time together for 20 months.

"Sometimes you are in that room together for hours on end. The jury are never told what is happening.

"Even when we were sat on the jury if someone needed the toilet we all went. We did everything together."

"The routine of going in every morning, and it's the same people in the same room, and you leave at night and you know it will be the same tomorrow.

"To be on my own now at work, it just feels strange. I've worked there for many years but I don't feel I belong there at the moment."

Anne-Marie said she had been back at work for nine weeks but was still retraining.

She says: "Everyone is very nice. It is nothing to do with work, it is just me personally. I don't feel I belong there any more."

During the lengthy trial, three of the jury dropped out, leaving the final 12 knowing that the trial would collapse if any of them gave up.

Anne-Marie says: "My husband was quite ill for part of it and they did give me time off for hospital appointments, but you felt you didn't want to ask because we wanted to be there, we wanted it to carry on, we wanted to get to a conclusion because we'd all gone so far.

"We wanted to see it to the end. It was an added responsibility when it went to 12."

Anne-Marie and the others all agree that lessons could be learned from their experiences for any future long trial.

But she says: "There will never be lessons learned because they won't come back and ask us."

- Published16 May 2017