UK fracking not viable, claims Edinburgh geologist

- Published

- comments

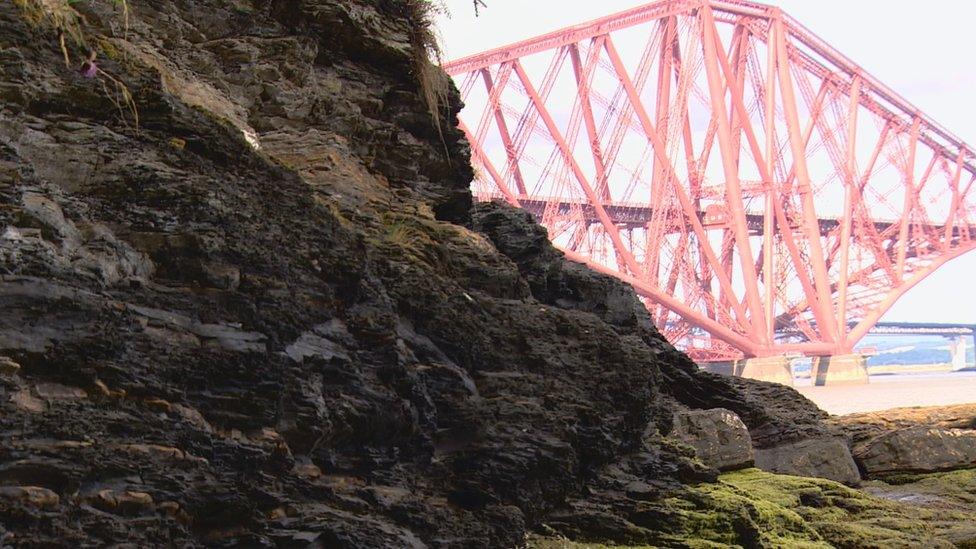

Exposed Lothian oil shale can be seen near the Forth Bridge

Fracking for gas will not work in the UK, according to research carried out at Heriot-Watt university.

Prof John Underhill said the geology of the British Isles will not support it. The fracking debate, he has claimed, is 55 million years too late.

Prof Underhill is Heriot-Watt's chief scientist and professor of exploration geoscience.

He said the rocks containing shale deposits in the UK are riddled with fractures.

They are "like a pane of shattered glass" and will make large scale fracking unviable.

Chemicals and oil products giant Ineos said it was pleased a Scottish University was "engaging in the science" of fracking.

However, it believed there was insufficient data to draw clear conclusions and more core sampling from between 5,000 to 8,000 feet needed to be carried out.

The energy industry has been fracking for decades.

Hydraulic fracturing, to give it its proper name, involves pumping a fluid - usually water plus additives - into rocks containing hard to reach energy deposits.

The water pressure fractures the rocks, the additives keep the fractures open just enough for the oil or gas to emerge and be captured.

It's a commonplace procedure offshore in the North Sea oil industry.

Prof Underhill doubts if the UK's geology makes it suitable for fracking

The present day debate about whether or not to frack has been inspired by the American experience of onshore fracking of underground shale deposits to produce gas.

Fracking's proponents say it has lowered energy prices and made the US self-sufficient in gas.

Its opponents raise deeply held environmental concerns, among them water contamination, waste and gas escapes.

The pattern of that debate has been mirrored here in the UK.

Wrong, says Professor Underhill. Both sides should have asked a geologist first.

Rocky outcrop

He takes me to the shoreline just below the Forth Bridge at South Queensferry.

We're going looking for oil and gas and it doesn't take us long.

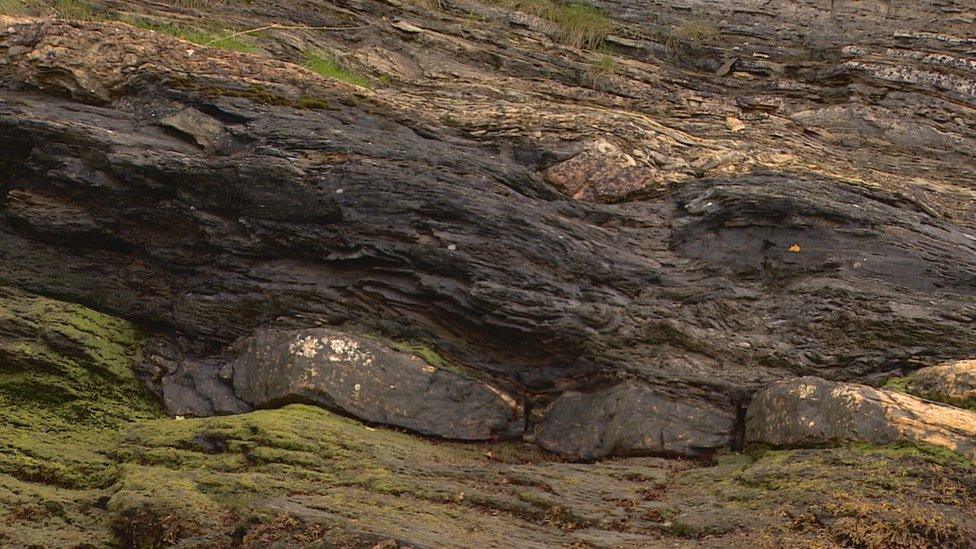

Out of the bank of the Firth emerges a rocky outcrop.

Among its many strata, a band of inky black rock.

Flakes of the rock break off easily when you touch them. Were you to heat them, oil and gas would emerge.

Oil shale seams can be seen in many parts of central Scotland, including South Queensferry

This is where the West Lothian Shales come to the surface.

Deposits like these are what excite fracking's supporters. Just not here at the surface.

Successful gas extraction requires shale to be underground at just the right temperature and pressure.

That's how it happens in the US. A drill digs deep, then turns to push and frack horizontally along the shale deposit.

And that, according to Prof Underhill, is what can't happen here.

Because Britain is broken, geologically speaking.

Tilting islands

Fifty-five million years ago the rocks on which the British Isles stand were pushed up against continental Europe.

They began to tilt, with the biggest uplift in the northwest.

The Western Isles contain the UK's oldest exposed rocks. They were once 3km deeper than they are now.

The southeast was lifted much less, which is why the geology beneath London is far younger.

Subjected to enormous forces, the rocks didn't just lift but folded and fractured.

Fracking has been credited with bringing cheaper energy to the United States

The professor produces a map showing what lies beneath.

A tracery of black lines show where fault lines shatter some of the UK's biggest shale deposits: West Lothian, Bowland Shale in Lancashire, the Weald Basin.

"For extraction to occur," he says, "you need a simple geology in the subsurface.

"So you can drill and then drill horizontally for long distances with confidence. Not go up, down, around.

"If you've got a fractured subsurface and something that's uplifted, you've switched off the kitchen in which oil and gas is generated - and you've broken the rock so it's not continuous."

Prof Underhill's assessment is unlikely to kill the fracking debate here. But energy prices could make smaller scale extraction viable in some cases.

It could mean the debate shatters into more localised controversies.

But it raises another important question: where are our future energy supplies to come from?

The UK ceased to be self-sufficient in gas earlier this century.

Now we depend on imports to keep us topped up.

Ineos' operations director, Tom Pickering, highlighted that the UK was importing more than 50% of its gas.

He added: "The opportunity to find it beneath our feet and safely produce it is an economic prize we think is worth understanding through this science."

Mr Pickering went on: "Gas is a building block as well for the basic plastics and chemicals that make the technology that harvest renewable sources.

"So, this is not about renewables verses fossil fuels, this is actually about gas being one part of an energy mix and exploring whether or not, and we don't know, because the 3D and the samples that we would like to take across the UK will give a guide to whether this is a real prize or it is not."

While the Scottish government has imposed a moratorium on shale exploration, UK ministers have been looking to shale gas to bolster the energy mix.

Without it, how will we keep the home fires burning?

Heriot-Watt University says Prof Underhill's work on hydraulic fracturing has been done in his capacity as the university's chief scientist. It says his work at its Shell Centre for Exploration Geoscience is independent of Shell and is also supported by government research councils and other funding agencies. He has not received any research funding for activities associated with hydraulic fracturing.

- Published31 January 2017