The university that broke the mould turns 50

- Published

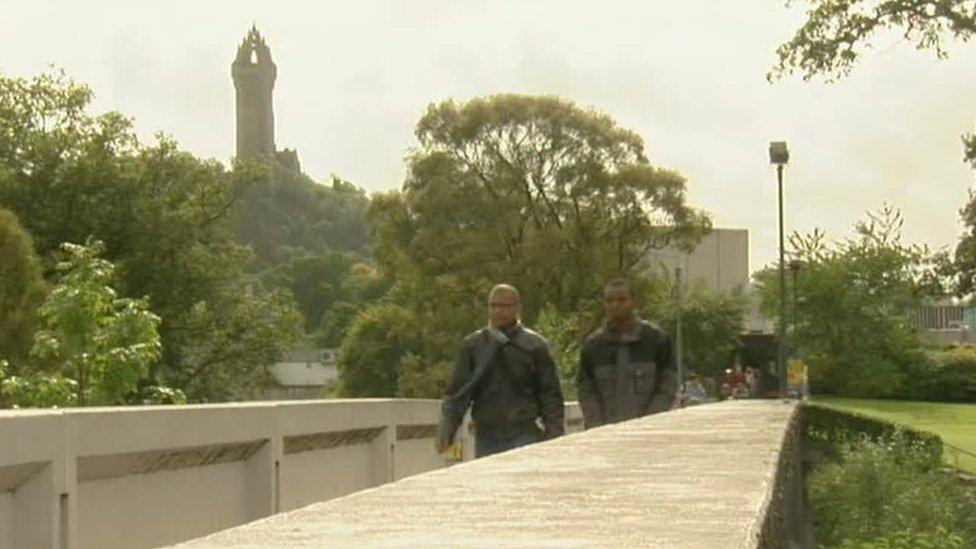

Stirling University is now 50 years old

Fifty years ago this week Stirling University became Scotland's first brand new university for more than four centuries.

During the 1960s a new wave of universities were established in Scotland as part of a great expansion of higher education across the UK.

Strathclyde University, Heriot-Watt and Dundee grew out of existing institutions but Stirling was different.

The others had a back story - for instance Strathclyde's reputation in science and engineering built on the work of the Royal College of Science and Technology.

But Stirling, as a brand new institution, had to work hard to make its reputation from scratch and its whole set-up was an alternative to the existing structure.

For example, it was the first Scottish university to pioneer a "semester" system for students - one which is now adopted by others.

Initially it was probably seen as the most radical of Scotland's universities.

An incident in 1972 in which some students jeered the Queen when she visited caused a national uproar and cemented this reputation.

One student from the early days recalled the difficulties which led to extra stress for undergraduates and the anger when the Queen visited.

He spoke of unfinished campus residencies which meant some students had to live as far away as Callander, the scarcity of course books in the library and the pressure which the then novel semester system led to - especially how coursework and essays counted towards final marks.

It took years for the university to overcome its difficulties but its radical edge faded as it became a more established institution.

Expansion of universities

The drive for new universities came from a report published in 1963 which was commissioned by the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan and chaired by the economist Lord Robbins.

It recommended an immediate expansion of universities and that all Colleges of Advanced Technology should be given the status of universities.

As a result of this, the number of full-time university students across Britain was to rise from 197,000 in the 1967-68 academic year to 217,000 in the academic year of 1973-74.

The Robbins Report also concluded that university places "should be available to all who were qualified for them by ability and attainment".

It said the institutions should have four main objectives essential to any properly balanced system:

instruction in skills

the promotion of the general powers of the mind so as to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women

to maintain research in balance with teaching, since teaching should not be separated from the advancement of learning and the search for truth

and to transmit a common culture and common standards of citizenship.

These were broad principles which Stirling was to follow. Indeed Lord Robbins was to be Stirling University's first chancellor.

Several sites were considered for the new university including Perth, Falkirk and Inverness before Stirling and its campus on the edge of the town was picked.

Until the 1960s there were just four universities in Scotland - Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and St Andrews - although several other institutions had the power to award degrees.

Actually going to a university was, in many respects, seen as a privilege.

For many years, a certain rivalry existed between Scotland's ancient and modern universities - in truth each institution had its strengths and weaknesses.

Another great expansion of higher education came in the early 1990s when many former polytechnics were granted university status.

Stirling has often performed well in studies of the so-called "pre-1992" universities.

As a general rule, the ancient universities still rank higher in international studies but it is hard to claim that so-called ancient and modern universities do not generally enjoy parity of esteem within the UK.

Stirling University today has some 14,000 full time and part-time students. It is no exaggeration to say that the institution has changed the character of the city of Stirling itself.

Indeed so many of the aims of post-war policy and the factors which led to Stirling University's foundation sound familiar.

The number of Scots going to a university - whether one of the ancients, one created in the 1960s or a former polytechnic - is around a record high.

All universities are expected to work hard to widen access and help youngsters from disadvantaged areas get into higher education.

But on Stirling's golden jubilee, it is worth reflecting on the role played by an institution which quickly became a respected part of Scottish public life and whose graduates - from the author Iain Banks to former first minister Jack McConnell - have contributed to society.

- Published12 October 2012