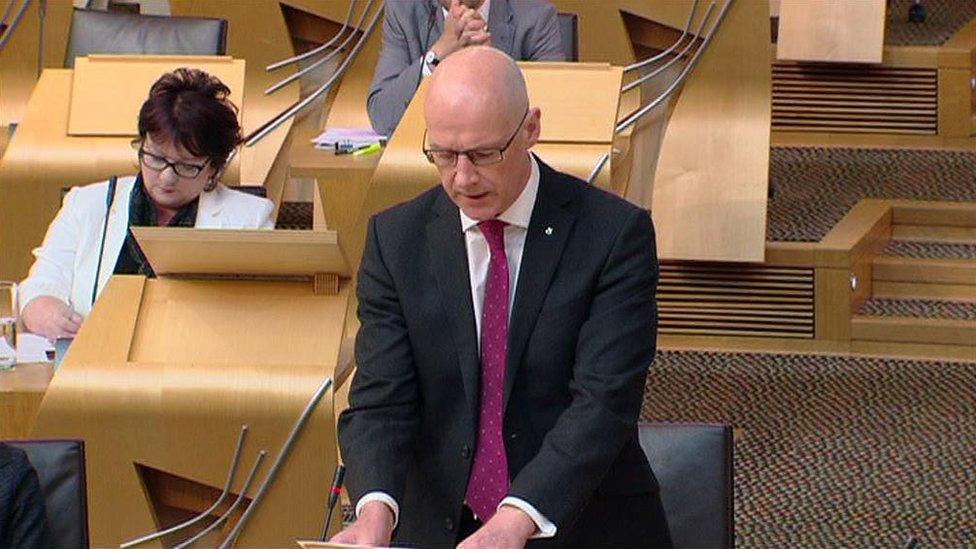

John Swinney defends education reforms

- Published

Mr Swinney is to speak at an event in Glasgow

Scotland's education secretary has insisted that he will press on with reforms in the country's schools.

In a speech in Glasgow, John Swinney said the government plans to give schools and teachers more freedom.

He also said that empowering schools will be at the heart of the next phase of reform.

The government plans to give more powers to head teachers and parents but there are still few details about what this will mean in practice.

Some heads wonder whether they will simply be given official responsibility for things they already do in practice through local management structures or - despite government reassurances - fear extra bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, some in local government fear they will have less control over education and that the changes could actually lead to more centralised control - a claim the government denies.

Governance changes

The government has also made it clear that the governance changes will not lead to grammar schools, or schools leaving local authority control completely.

Mr Swinney made his speech at the Scottish Learning Festival in Glasgow, a major event attended by teachers, heads and others in education.

He said that empowering schools and freeing teachers to teach is at the heart of Curriculum for Excellence and of the next phase of school reform.

Mr Swinney said he recognise the challenge this poses to the teaching profession but told the audience there will be no return to the era of prescription and top-down diktat.

The Curriculum for Excellence was introduced in Scotland's schools in 2010

Curriculum for Excellence was always designed to try to give teachers the freedom to take the approaches to learning which they felt were right for their school or class.

Mr Swinney argued that the next stage of teacher empowerment - the reforms to school governance - will build on the freedom that CfE provides.

Speaking ahead of the event, he said: "When Scotland set out to reform our school curriculum, a critical question was how we break free of the top-down diktats that dominated Scottish school education. Teachers were teaching to the test and children were not receiving the broad knowledge and skills they needed.

"We chose to free our teachers to teach, to be free to educate our young people and prepare them for a world that is ever-changing.

"It was a decision that asked a lot of our teachers. CfE is founded on teacher-led learning. That liberated teachers from the prescription of the past but it also asked them to take on the challenge of shaping the curriculum as best fits the individual children in their classrooms.

"It was a decision based on our faith in teachers' professionalism, dedication and expertise."

'Right decision'

He added: "That's why I have no doubt that it was the right decision. We will not go back to an approach that was designed for a previous era and that, bluntly, would leave our young people ill-prepared for the modern world.

"Instead, we will go further. We will give schools and teachers more freedom.

"Through our new reforms, we will put more powers in the hands of head teachers and give teachers even greater freedom to teach. And we will back that up with more professional development and more professional support.

"We will press on with reform. We will keep faith in our teachers. And, together, we will build a school education system designed to equip our children for the future."

The government's critics have highlighted the lack of progress improving literacy and numeracy standards, some difficulties filling vacancies and Scotland's worst-ever performance in the respected international Pisa table as evidence of failures in education policy.

Disadvantaged backgrounds

Supporters point to exam results, an OECD report highlighting Curriculum for Excellence's potential and the fact few teenagers are not in education, work or training as evidence of progress - although they accept progress needs to be made in many areas.

One priority for the government is to help more children from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds do better at school and gradually increase the proportion who go to university.

Schools already receive extra money straight from the government which head teachers can spend on whichever schemes they believe might help raise attainment.

Government supporters argue reforms to school governance will make it easier for head teachers do what they think is best for their local circumstances, although critics say changes to governance alone will do nothing to improve performance.

New standardised assessments currently being introduced in primary schools and the early years of secondary are designed to make it easier to show which schemes to raise attainment are working best.