How the early years shape a child's whole life

- Published

There is a growing recognition that what happens in a child's early years can affect their whole life for good or ill.

One charity active in the field - Early Years Scotland - is celebrating its half century at a conference of experts on Saturday.

So how have ideas changed over that time?

"He loves it, he's got his own wee friends here now," says one mum at an early years group in Glasgow.

She comes most weeks with her 21-month-old son.

Unlike the usual nursery set-up this "Stay, Play and Learn" session is about parents or other adults staying with the children.

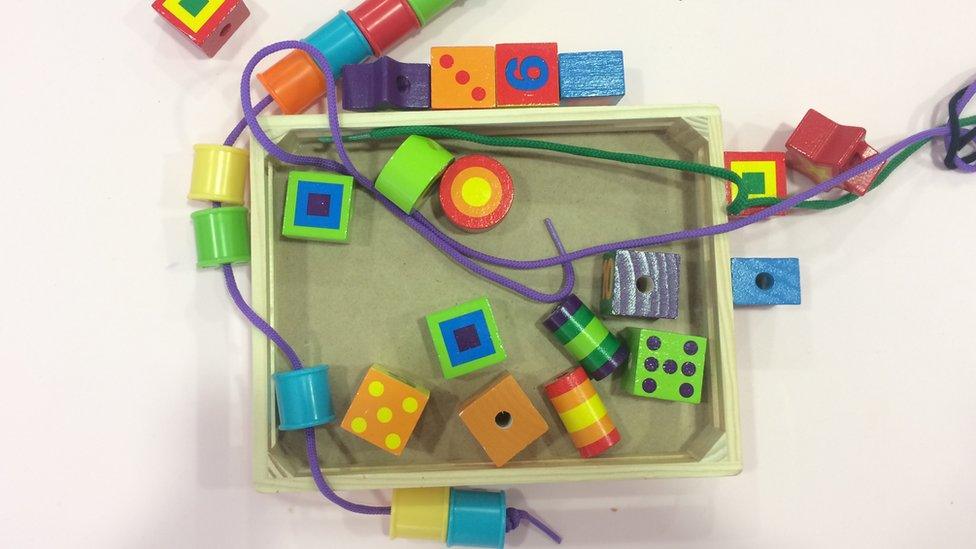

Among what is on offer, there are books, a little toy cooker, blocks and other toys.

Another of the mums, who is a regular with her two-year-old, says it is great for his social skills and getting him ready for his next stage at nursery.

"At least he won't be thrown into this big space without knowing how to behave towards other kids," she adds.

About 11 families come fairly regularly.

The aim is to give them ideas of things to do with their children at home, like today's session on making empire biscuits.

"It's amazing how many parents don't know these simple activities and how much learning goes on," says early-years practitioner Pauline Scott.

She adds that she has seen both adults and children grow in confidence.

"We've been talking about colours, ingredients, different simple activities you can do at home," she says.

"We know that what happens in the very earliest years, actually from pre-birth, can be a very strong predictor at that stage of what happens much later on," says Jean Carwood-Edwards, chief executive of Early Years Scotland.

She thinks that how we view the early years has really changed and much of that is down to the fact that we know so much more about the way children learn and develop.

That can be apparent by the time they start school.

"There are so many children that if they have had a less advantaged start they're already way behind in terms of their language development, in terms of their cognitive ability," Ms Carwood-Edwards says.

"The more we can do in the very earliest years with parents to try to give them the very best start the more difference it makes not just for the children at that stage, but for their lives."

The idea that a child's early years are important is not a new one, even though in previous decades there was not so much around for them.

Throughout Britain in the late 1960s and early 1970s pressure came from grassroots movements promoting more provision for young children.

It ended up with community groups opening up in church halls and the like.

"It began as a pressure on the state to provide more nursery education free and it ended up as an alternative," says Aline-Wendy Dunlop, emeritus professor at Strathclyde University.

'Incredibly rewarding'

Her career in early-years education began almost 50 years ago.

By the time the state did become engaged, she adds, there was a real variety of provision from private nursery schools, pre-school play groups and community groups.

It is a mix which endures to this day.

Work is already under way to increase free early learning and childcare but while lots has changed some argue that there more to done in terms of showcasing and promoting the sector.

Ms Carwood-Edwards says many people think of it as a "career that you do if you can't think of anything else to do, or you're not every academic," rather than something which is very diverse and can be "an incredibly rewarding".

She lays at least part of the explanation for this at levels of pay which in her view are "still far too low".

"I would go so far as to say that working in the early years sector is the most important job in the world, not that I'm biased, but I would say you really are shaping the future," she said.