The Scots who fought in the battle for Jerusalem

- Published

General Allenby marches in Jerusalem in 1917

At noon on 11 December 1917, British commander General Allenby marched in to Jerusalem after overthrowing the Ottoman Empire and becoming the first Christian to control the Holy City in 730 years.

Thousands of Scottish soldiers played a key role in the push across the territory then known as Palestine towards the city, which is held holy by three major religions.

Having secured it, Allenby approached the Jaffa Gate outside Jerusalem and dismounted from his horse.

He and his senior officers entered on foot out of respect.

It is said that many wept for joy and priests embraced but Allenby was aloof and unmoved.

General Sir Edmund Allenby (1st Viscount Allenby) in Jerusalem in a Vauxhall staff car

TE Lawrence, or Lawrence of Arabia, was among the officers - wearing a borrowed uniform rather than his customary Arab garb.

He is a well-known figure - but Britain's fight against the Turks at the beginning of the final year of World War One is not a well-known story.

It's called the "forgotten war" and doesn't feature in our typical view of Tommies on the Western Front stuck in trenches.

General Edmund Allenby in conversation with an Army officer in Palestine

The Ottomans had controlled the region for more than 400 years in a brutal and repressive regime.

The military success in overthrowing them came at a price.

Overall, the British Empire troop death toll was about 28,000.

The 52nd Lowland Division - whose soldiers were mainly drawn from central and southern Scotland - was among the Scots units who played a key role in the battles that led to Jerusalem.

Of the 11,000-strong division, 920 were killed, 304 reported missing and 4,306 were wounded.

And this was a Territorial Army unit - the men in it were not career soldiers.

A British group were taken on a tour of the route fought by the 52nd Lowland Division

A century after the operation, Colonel AK Miller, the former British military attaché to Israel, has been leading a group of Scots, many with connections to the troops who fought, on a tour of the route they followed.

Colonel Miller, the former Commanding Officer of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, said it was a campaign of "fast manoeuvre".

It was very different to the warfare of stalemate in the World War One trenches of France and Belgium.

He said: "They advanced from the Suez Canal to Tel Arsuf, north of modern-day Tel Aviv, in doing so, crossing from the coast to the Judaean hills and back."

The troops laid miles of railway track each day as they advanced

I made my own "advance" with the tour, as we drove from Jerusalem down to near Ein HaBsor.

In desert-like conditions, we found the remains of a railway the British built to bring vital supplies north up the line and, of course, the wounded back down the line.

Colonel Miller stood on the vast, sandy embankment constructed 100 years ago.

The railway was built in desert-like conditions

He explained that more than a mile a day of railway track was built

"I think that would challenge most railway companies these days to do anything similar," he said.

"The last part of this line - about 7km (4.35 miles) - was actually built in the direct lead-up to the battle and they were almost laying it as they went into action."

Colonel Miller's wife Carol is seeing the area where her grandfather operated

Colonel Miller's wife Carol is seeing the area where her grandfather, Lieutenant Kenneth McLelland MC, operated.

He was in the Royal Engineers (Signals Service).

She said: "He died very sadly in 1938 as a result of wounds he endured here.

"So actually, to come out here - and I've done a lot of research, I've looked at the photographs - so I can just envisage what it would have been like for him.

"Looking at the small little truck that he used to take along the railway line with signalling equipment and thinking about the kilts, the heat - it is alive."

Lieutenant Kenneth McLelland was in the Royal Engineers (Signals Service)

The modern-day tour party then leaves the dusty remains of the railway track and climb on board their air-conditioned bus.

We head to Black Arrow viewpoint at Melfasim - but there is a problem.

A young Israeli Defence Force private is manning a checkpoint with his equally young colleague.

A marked police car is there with flashing lights and a barrier is across the road.

Turned back

"You can't go any further," he said.

"Hamas snipers are operating from Gaza this afternoon."

The tour bus and the BBC crew are turned back but we are signalled to stop again.

The guards ask: "Where is the BBC from? My colleague thinks America but I think the UK."

The youthful pair from the defence force were probably a similar age to the young men sent from Scotland to fight and die in Palestine.

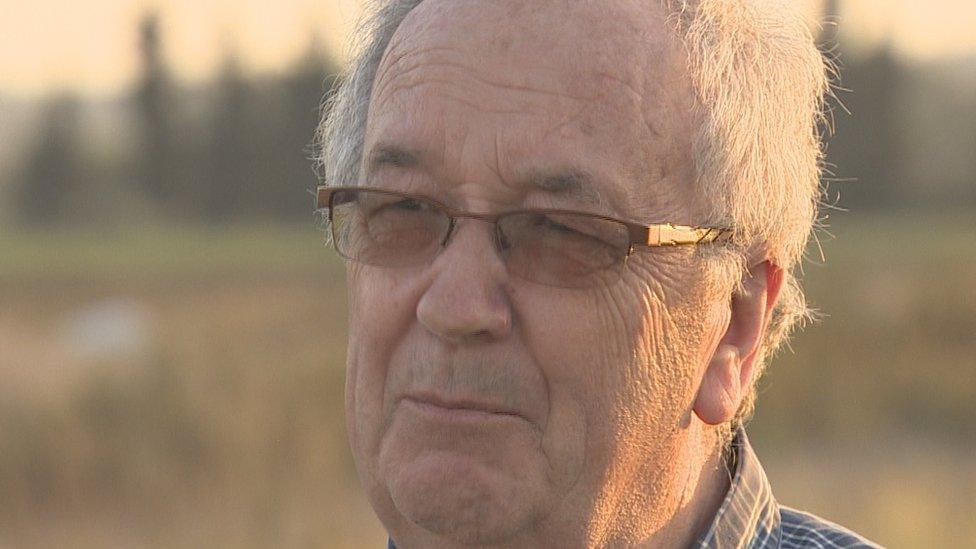

Walter Dunlop said his father-in-law had fought in Palestine

The "Jocks", as they were known in army parlance, had a tough fight at "Sausage Ridge" after the allies' success in the third Battle of Gaza.

A line of trees on a seemingly imperceptible incline proved to be much higher than thought as Turkish machine guns strafed the men.

On the tour, Walter Dunlop stopped there and spoke to us about his father-in-law, Corporal John Robertson.

Corporal John Robertson never said a word to his wife about his experiences

"He never said a word to his wife and his daughter about his experiences here in Palestine and, from what I understand of the gruelling march through the desert, the casualty lists - it was so bad that it traumatised many," he said.

Nevertheless, the Empire Expeditionary Force pushed on and the Gaza to Beersheba line held by the Ottomans collapsed on the Allies' third attempt to break through.

Another victory at Junction Station saw the Turks withdraw north and the British pursued them - but the going was tough.

Rough track

On the approach to Jerusalem, they marched 69 miles in nine days and that included four battles.

Animals were critical to the supply lines, with camels carrying water along a rough track that was an old Roman road.

More than 150,000 beasts were pressed into service. Mesh netting helped them cross the desert tracks.

The men had to march with only two days' worth of rations for three days as they approached the final, decisive battle on the road to the Holy City.

A synagogue and a mosque sit on top of a hill, a commanding position overlooking the route north from Jerusalem.

Kept on going

This is Nebi Samuel - it's said to be the tomb of the Samuel from the Old Testament - many have fought here, including the Crusader King, Richard the Lionheart.

Colonel Miller said: "It's said that Nebi Samuel has been the pathway to Jerusalem on 23 occasions throughout history.

Of the World War One Scottish troops, he said: "Their boots were worn out, their clothes were in shreds - in fact, the best of them were in kilts because they were a bit hardier but they never gave up and they kept on going."

Captain Ian Bell from Edinburgh saw his best mate killed at Nebi Samuel

It was a melancholic victory for Captain Ian Bell from Edinburgh, though.

Scrambling up the hill with Captain Bell was his friend Lieutenant John Hutchison, who came from Leith.

Lieutenant Hutchison was shot in the back and died later in the military field hospital.

Captain Bell wasn't allowed to see his mate to say goodbye.

Captain Bell's son Robin found Lieutenant Hutchison's grave

Now, 100 years on, I meet Captain Bell's son Robin in the Jerusalem War Cemetery and we find Lieutenant Hutchison's grave.

Robin, who is now 84, approaches and salutes smartly.

His wife Pattie lays a small rose.

It's possibly the first time in a century that any flower has been laid at this headstone as the Bells haven't been able to trace the lieutenant's family members.

Robin and Pattie at the grave of Lt Hutchison

After paying his respects, Robin said: "It was a very moving experience to find the grave of one of the dozens and dozens of soldiers of No.1 company that were killed in the war.

"It made my father have survivors' guilt, I think.

"He was quite affected by it all - although he didn't talk about it."

Act of Commemoration at Mount Scopus

The grave at Mount Scopus overlooks Jerusalem but on a ridge near the Old City there's another memorial.

St Andrew's Church and Hospice was built to remember the Scottish soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice.

It blends western and eastern architecture and is an oasis of calm in a tense city, with a sweet smell coming from the flowers as you go up the drive and a Saltire fluttering on the tower matching the bright blue, Jerusalem sky.

General Allenby laid the foundation stone of St Andrew's Church in 1927

General Allenby laid the foundation stone here in 1927.

The minister is the Rev Páraic Réamonn and he turned my attention to the present day.

Inside St Andrew's Church of Scotland Church

Speaking about Jerusalem, he said: "Allenby did see this place very definitely as a place of three faiths and hoped that they would co-exist together in peace - but that's not how it is.

"This is a place of conflict and it is a political conflict in its essence and until we find way of creating political arrangements that accommodate and include and embrace all the people who live here - there will be no end to the conflict."

The Dome of the Rock, an Islamic shrine located on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem

From the Kirk, you can see the Jaffa Gate where Allenby marched in.

The Citadel overlooks it - it's now the Tower of David museum.

Its chief curator showed me the ruins of the different rulers of the city - from King Herod, through to the Ottoman Empire and then to the British - who changed the place from a barracks into a museum.

Dr Eilat Lieber at the Tower of David Museum

Dr Eilat Lieber explained how the impact of the 1917 occupiers is still felt.

She said: "To bring the British rules to the city was to bring the west to the east and to talk about infrastructure, education - even today, Israeli law is based on the British one, the transportation based on the British one."

The Scottish soldiers helped the general achieve his aim of securing Jerusalem - but his ultimate hope of peaceful co-existence is a distant dream for many - unrealistic and perhaps even unwanted for others.

The Dome of the Rock and Mount of Olives in Jerusalem

For people like Carol, Walter and Robin, Jerusalem is place that continues to feature in the news - but for them and many others it's a place that holds memories of those who served.

In an undated, fundraising pamphlet for St Andrew's Memorial Church, probably from the late 1930s, the Reverend Dr Norman Maclean described Israel as "twice Holy ground" - the place that was the Holy Land but that also contained the burial grounds of Scots soldiers.

In a drive to raise money, an elderly man in a little country church offered the clergyman £100 after he'd mentioned the St Andrew's appeal during a service.

Dr Maclean said: "That is too generous of you."

The man simply replied: "No, I have a son lying among the hills of Judea".

That brings home the sacrifice of Scots soldiers with St Andrew's described by Dr Maclean as a "fitting memorial".