The night Robert Burns' skull was taken for a walk

- Published

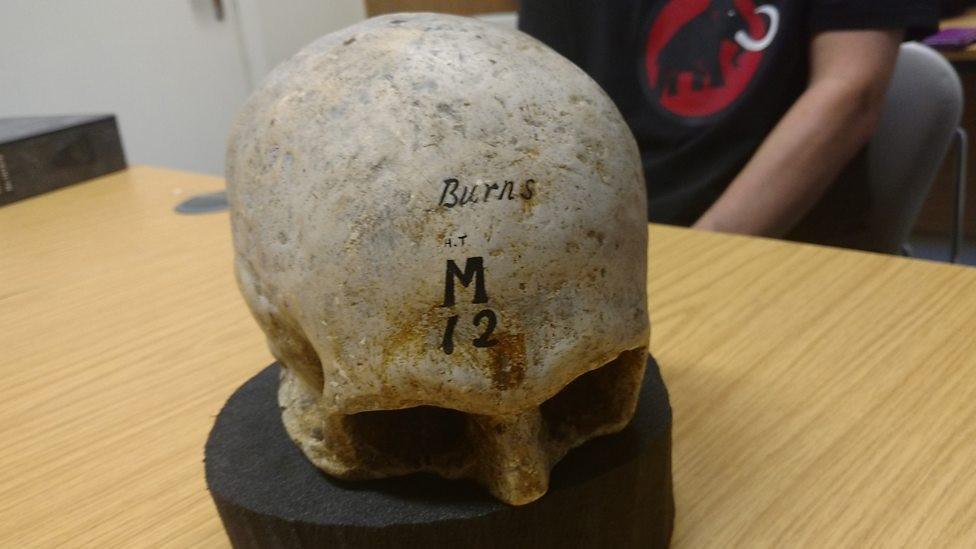

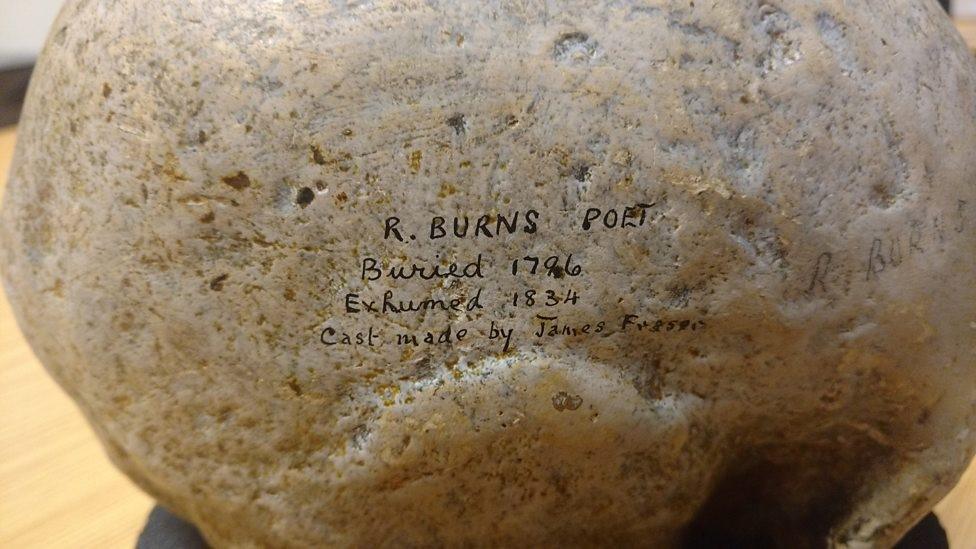

A cast of Robert Burns' skull is kept at the University of Edinburgh

One night almost 40 years after his death, the skull of Scottish poet Robert Burns was taken from his crypt by a group of Dumfries locals with a strange interest.

The men, led by newspaper editor John McDiarmid, were keen advocates of phrenology - a now discredited pseudo-science that believed you could read deep truths about someone's personality from plotting the bumps on their head.

McDiarmid and others were keen to study the skull of the ploughman poet - a man who was thought of as a natural genius and whose personality was well-known throughout the world.

Dr Megan Coyer, of the University of Glasgow, tells the BBC Scotland programme The Death and Resurrection of Robert Burns: "The phrenologists were interested in Burns because he was such an important character in the public imagination and therefore they wanted to see if the bumps on his skull would match up to his public persona."

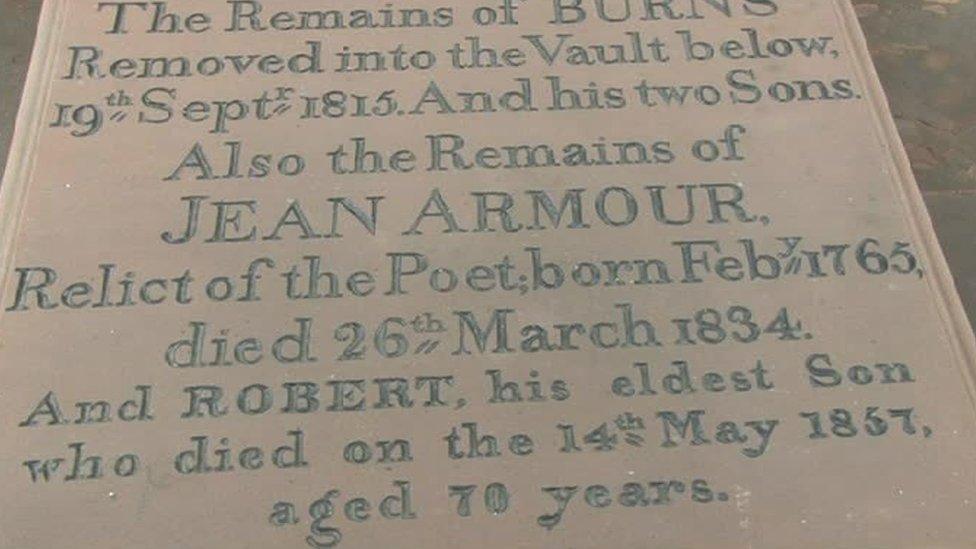

However, the Bard's widow Jean Armour was not thought to be keen to allow the phrenologists to disturb her husband's resting place because his remains had already been moved once before.

Burns' body was moved to his mausoleum in 1815, 19 years after his death

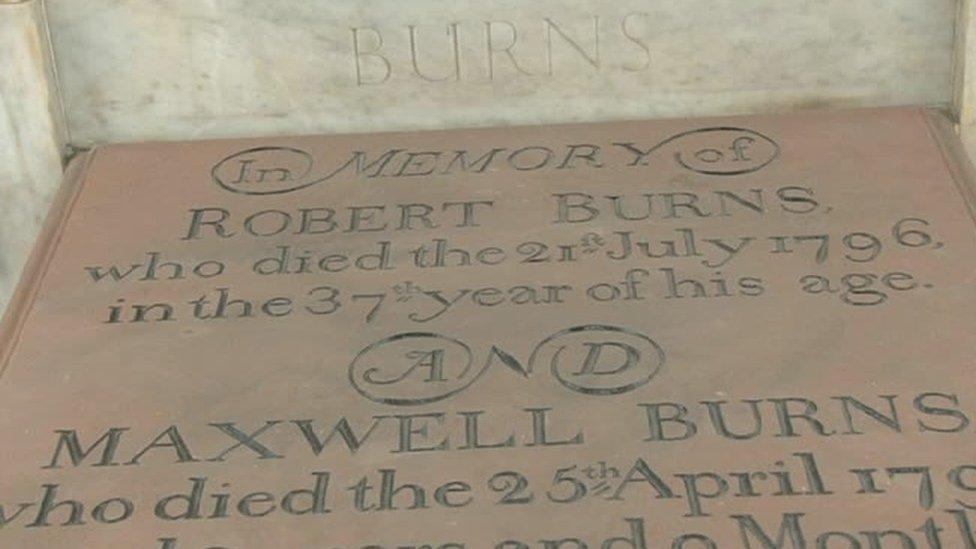

When Burns died in Dumfries in July 1796, he was not buried in the imposing mausoleum that currently stands in the town's St Michael's kirkyard.

The bright, white, rock star tomb, with its pillars and domes and its marble figure of Burns at the plough, was erected 19 years after his death, following a long fundraising effort.

His widow was disgusted by the gruesome exhumation of the poet's body, and the remains of two of his sons, to the relocate them to the new monument.

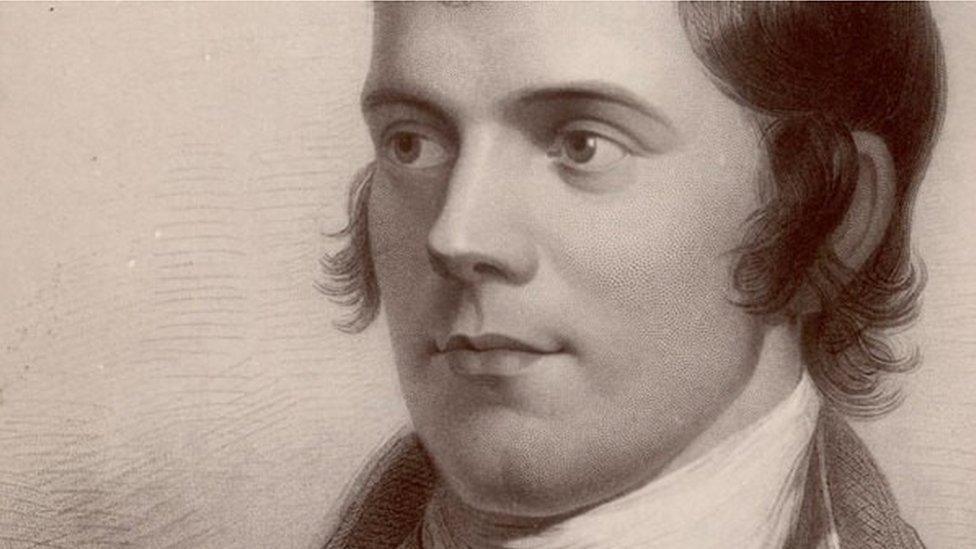

Robert Burns' poems and his life story were known throughout the world

Dumfries Courier editor McDiarmid wrote an account of removing Burns from his original resting place.

He told how when the workmen tried to lift the original wooden coffin "the head separated from the trunk, and the whole body, with the exception of the bones, crumbled into dust".

The newspaper editor may have been accurately describing the scene but he was not there at the time.

He arrived in town two years after the event and must have cursed his luck at missing out on getting his hands on Burns's skull for a phrenological study.

The Burns mausoleum features a marble statue of the poet at his plough with the muse above him

It was not until Jean Armour died in 1834 that another opportunity arose to get a plaster of Paris cast of the skull.

McDiarmid realised the crypt of the mausoleum was going to be opened and he appears to have obtained permission from Jean's brother to take a cast of the skull.

Burns' widow Jean Armour died in 1834, 38 years after the poet

The group carrying out the plan comprised of six men plus their assistants, and by the end of the night the Provost, the Dean of Guild and rector of Dumfries academy as well.

Historian Louise Yeoman says: "They don't want to be seen and they don't want a mob to assemble and say 'here they are violating the poet's grave, we are going to stop them'.

"They make their first attempt at 7pm but there are too many people about.

"At 10pm in come our boys again over the walls, sneak up to the mausoleum with the keys, they go down into the vault with a ladder and a muffled lantern so people don't see the light."

The Burns Mausoleum took many years to fund

Ms Yeoman says that according to Burns' experts who reconstructed the process, McDiarmid had thought he would be able to take a plaster cast of the skull in the vault but he realised he couldn't.

So he popped it into a linen bag and walked it up the high street to Queensberry Street where the plasterer James Fraser worked.

The historian says: "They make a mould and from that they take a cast of the skull."

Dr Coyer adds: "There are several persons involved, one of which is the surgeon Archibald Blacklock and according to the published accounts he, very scientifically, handles this skull.

"He also apparently tries his hat on it out of awe, because the skull is so large he wants to know if his hat can fit on it or not.

"The workmen around him then all apparently try their hats on Burns's skull as well."

The freshly-cast skull was rushed to Edinburgh, to George Combe, the master of phrenology, who prepared a report on Burns' personality.

Phrenologists believed the brain was made up of 27 individual "organs" that determined personality and these could be measured by studying the shape of the skull.

Combe's report rated Burns for a number of character traits based on the size of the "organs".

A figure of a mouse appears in marble on the Burns mausoleum

Dr Coyer says one of Burns' organs that was very large was his organ of philoprogenitiveness, his ability to produce and care for children.

Along with a high score for benevolence, the phrenologists said this explained his love for weak and helpless creatures displayed in poems such as To a Mouse and On Seeing a Wounded Hare.

Dr Coyer says: "A lot of it is just talking about the poetry and the life and trying to make sense of this scientific analysis in relation to Burns' well-known public character and his written work."

This was a "risky" strategy, she says, because Burns was so well-known that if their findings had been at odds with his public persona it would have made phrenology look like a fraud.

"So they work very hard to make sense of these materials," she says.

The cast of the skull at the University of Edinburgh is likely to be one of the originals

David Price, professor of developmental neurobiology at the University of Edinburgh, says the phrenology report is an example of "confirmation bias".

He says that instead of the scientific philosophy of trying to prove your hypothesis wrong, the phrenologists wanted to confirm their prior beliefs.

The anatomical museum of the University of Edinburgh has a cast of Burns' skull which is likely to be one of the original copies made that night in 1834.

Examing it, Prof Price says it is a "typical skull of a Caucasian adult".

"There is nothing about it which is particularly striking," he says.

"It has an enlarged occipital lobe at the back. It is apparently pretty intact.

"It is unremarkable, essentially, much probably like my skull."

- Published25 January 2018

- Published24 January 2018