Future fuel quest takes a step forward

- Published

- comments

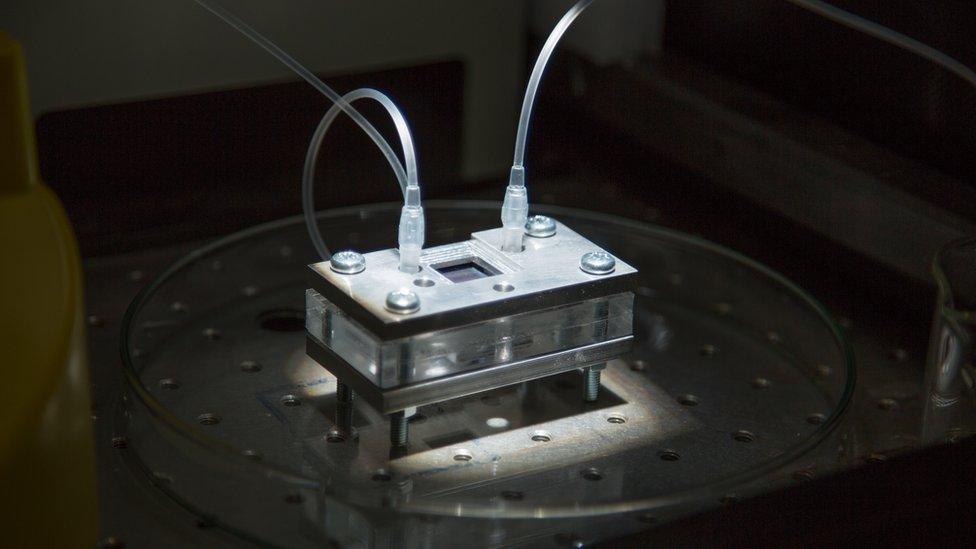

The new cells can produce hydrogen from water using far less electrictiy

A team of Scottish-based scientists has developed a new technique for creating hydrogen fuel.

Working at Heriot-Watt University, they've created a system that uses sunlight to create hydrogen more cheaply and efficiently than before.

Hydrogen is the lightest element in the Universe. A gas at room temperature, it burns with oxygen to give off heat and water vapour. (In air there are also small amounts of nitrogen oxide.)

Unlike carbon-based fossil fuels, there is no carbon dioxide (CO2) to add to the planet's climate concerns. It is that feature which has made it a prime candidate to be a major part of our future energy supplies.

Water splitting

But before what has already been dubbed the "hydrogen economy" can fully develop, it first has to be economical.

Hydrogen can be produced using fossil fuels, which adds to CO2 emissions.

Another, cleaner method appears simple: harvest energy from the sun using solar cells, then pass the resulting electricity through water. The water splits cleanly into hydrogen and oxygen.

It's called PEC - photoelectrochemical water splitting.

So far, so simple-sounding. But it is not particularly efficient. It costs twice as much to produce as energy from wind and biomass because you have to put a lot of energy in to get the hydrogen out.

One method of improving efficiency is to put the two electrodes into fluids with different values of pH - one acidic, one alkaline. But they must be kept apart by a membrane and that brings further problems.

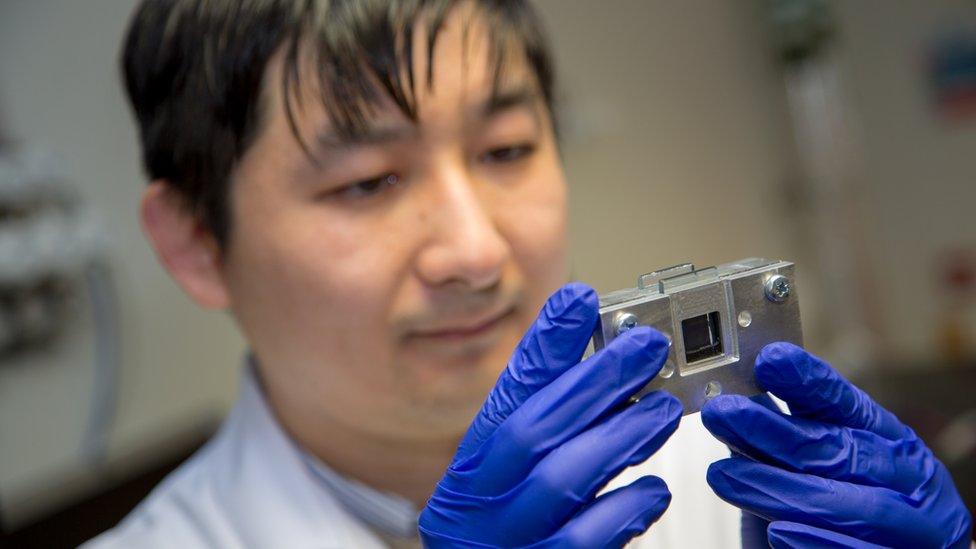

Now Dr Jin Xuan has developed a new type of PEC cell which he says "will use cheap, widely available materials that mean the technology can be easily scaled up to meet the growing demand for hydrogen fuel".

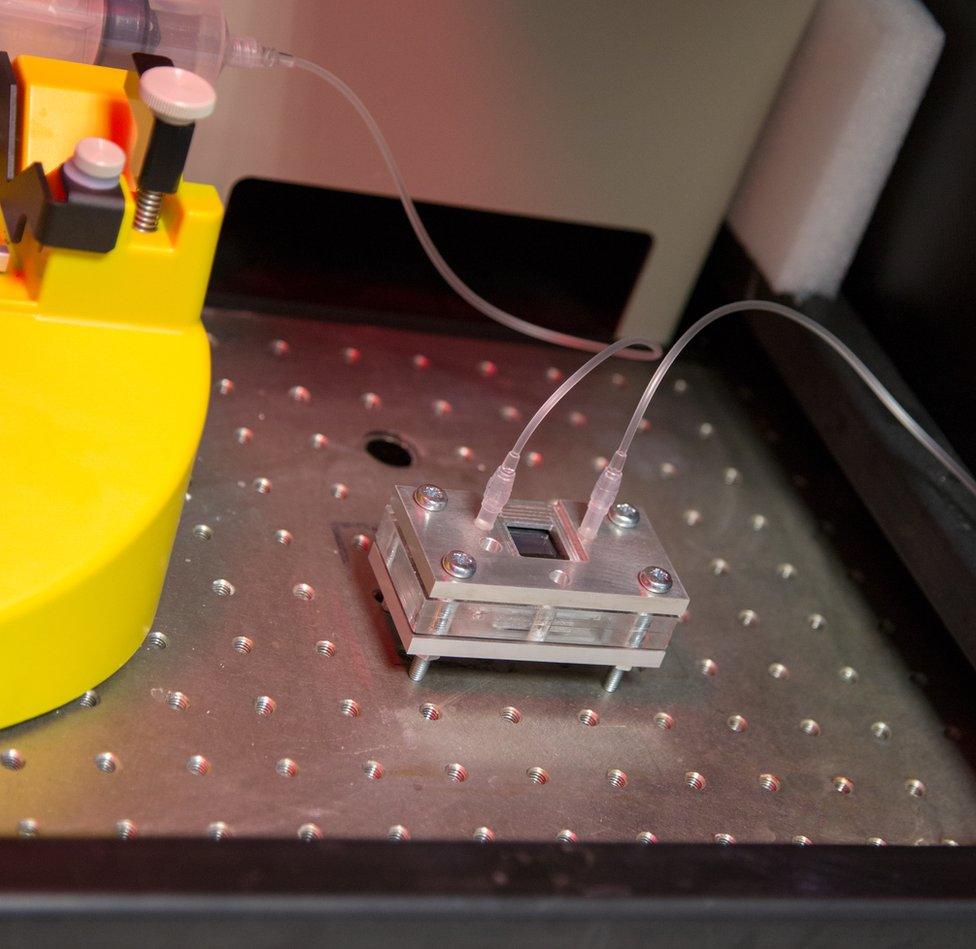

Dr Xuan - assistant professor of mechanical engineering and the associate director of the Research Centre for Carbon Solutions at Heriot-Watt - shows me the reactor. (It's a photoelectrochemical, not nuclear, one.)

It is about the size of a paperback book. A daylight lamp stands in Scotland's sometimes fickle sunshine.

On the top, solar cells produce the electricity which in turn unlocks the hydrogen and oxygen.

Before now, energy of at least 1.23 electron volts (eV) was needed to split the water. The new device has lowered that to just 0.35 eV.

Electrode design

It uses a much wider spectrum of sunlight where earlier cells could only employ the energy from ultraviolet rays.

At the heart of the process is a fundamental redesign of the electrodes that deliver the electricity into the water.

It's called a pH-differential design. A pattern of laser-cut channels each no thicker than a human hair creates a microsystem which makes one electrode acidic and the other alkaline without the need for a membrane.

It reduces the cost of PEC water splitting by about two-thirds and increases the solar-to-fuel efficiency by up to 20%.

The team is being funded by the UK's Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and is collaborating with researchers from Yale University's Energy Sciences Institute, the City University of Hong Kong and East China University of Science and Technology.

"We have already proved that this system has potential," Dr Xuan says.

"We've applied a similar design strategy in a number of energy devices, such as fuel cells and batteries."

There are still many hurdles to be overcome before hydrogen fuelled trains and cars become commonplace. One - almost literally - burning issue is the safest way to store large quantities of highly flammable gas.

Dr Jin Xuan believes the technology could be used to power whole communities

Heriot-Watt's reactor design is itself still in the laboratory. It will take more work before it can be scaled up and brought to market.

But Dr Xuan is already thinking about one specific way in which it could be used.

"My home is now in Juniper Green. It's a small village near the university," he says.

"If you can install centralised fuel cells there you can generate heat and electricity to power the whole community.

"I think our device will one day achieve this target."

What may one day work in Juniper Green could also work worldwide.