How do head teachers spend the pupil equity fund?

- Published

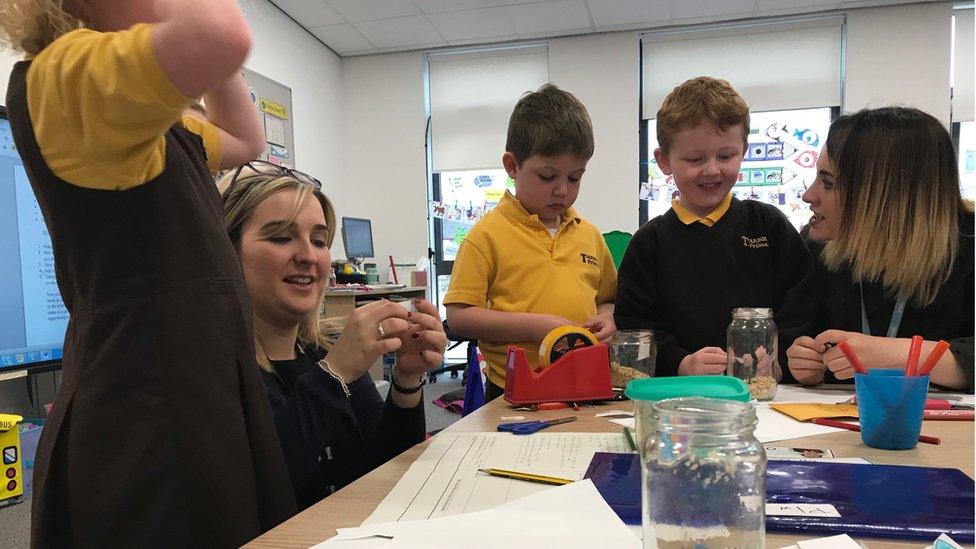

P1 teacher Jennifer Wallace (left) and early years practitioner Megan Hainey (right)

Money earmarked to improve the academic performance of disadvantaged children goes directly to head teachers but how do they choose to spend it?

Another school day gets under way at Tarbolton Primary.

The 193 pupils now occupy a brand new building replacing the loved but leaky old schoolhouse.

They have been in the new premises for around a year, roughly the same amount of time the Scottish government's £120m Pupil Equity Funding (PEF) scheme has been in place.

The scheme came from the desire of Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish government to close the poverty-related gap in educational achievement.

PEF aims to give children from poorer homes the same life chances as those in more affluent areas.

The actual cash allocation under the policy of £1,200 per child is based on the number of children qualifying for free school meals.

So Tarbolton Primary got £72,000 in 2017/18, and will get a little more in 2018/19, about £20,000 more than the national average.

The policy manifests itself in different ways in different schools and here in South Ayrshire it is head teacher Jackie Blair who decides how to spend the cash.

Head teacher Jackie Blair says she knows what her school needs

She says that as a head teacher she knows her school inside out.

"You know where you want that money to go and you know where you think that money can make a big difference," she says.

"So to be able to work collegiately with your staff and make decisions locally is massive."

Ms Blair is using the money to focus attention on the first three years of school, seeking to set solid foundations for the future.

One example is funding an early years practitioner to support class teachers.

Ms Blair says that the school had always managed to raise pupil attainment but it could often take until the final year of primary to see the results.

"What we want to do is make that difference earlier because if we can do that, where might they be by the time they get to primary seven?"

Education Secretary John Swinney said boosting schools was the government's "defining mission"

Teaching about the fish in the sea and some big words to go with them is Primary 1 teacher Jennifer Wallace who says the in-class back up from an early years practitioner makes a huge difference across the ability spectrum.

Ms Wallace says: "I think a lot of people have the perception that because all pupils are starting primary so they are all at the same level.

"That's absolutely not the case.

"It depends on home life, it depends on experiences in nursery and it depends on how engaged they are in learning."

The primary one teacher says: "We are able to reach all learners because you have got that extra pair of hands in class, which then further raises attainment."

Running around in the playground is important to let off steam, but play itself has been identified as something PEF money can help with in terms of socialising, confidence and imagination.

Early years practitioner Megan Hainey uses everyday objects like sticks and even cardboard boxes to help play and learning.

Ms Hainey: "The cardboard box can become a microwave one minute then it's a rocket.

"It's just about getting the children to use their imagination and they absolutely love it.

"We feel that's had a good impact when it comes to doing the imaginative writing."

The notion of play and activity goes even further.

Deputy head Helen Ross says new ways of improving pupil confidence can be tried

Deputy head Helen Ross says using pupil equity funds to take 14 children, some as young as primary 2, who struggled to integrate into school life, on a four-day residential course had a big impact back in school.

She says skills learned from activities such as abseiling fed right back into the classroom.

Ms Ross says: "They became very confident, responsible, working together very much as a team.

"That comes back into the classroom and the relationships they have with their peers when they are back in the class and the attitudes and relationships they have with adults in the school also."

The first minister launched the Scottish Attainment Challenge three years ago in February 2015.

The SNP hopes the policy will help reverse a sharp decline in Scottish education's international ratings, from organisations like PISA.

But opponents such as the Scottish conservatives see the policy as a fig leaf covering up fundamental problems in areas such as teacher recruitment, retention and training, pointing out that the profession has 3,500 fewer teachers than when the SNP came to power almost 11 years ago.

Head teacher Jackie Blair says: "I personally haven't had an issue with staff recruitment.

"I think you have to recognise it is not having 100 teachers, it is having 50 particularly good teachers.

"I think that when you can give staff the resources the money and the autonomy to do what they can do best then that's when you are going to get the good results.

"I don't think it is just about filling the gaps with a body.

"It's about filling that gap with the correct person and using the money for training and resources to allow people to do the job they love is more important."

Here at Tarbolton Primary staff say PEF has made a difference and is helping to close the attainment gap.

They also seem to like the fact that in a profession full of prescription about what they have to do there is an area where they can decide for themselves.

Whether other factors like teacher numbers and recruitment are an issue more widely is a matter for politicians to argue about.

At the end of the school day the children head home happily oblivious to government policy.

And that's probably just how it should be.

- Published30 January 2018

- Published24 July 2017

- Published11 May 2017