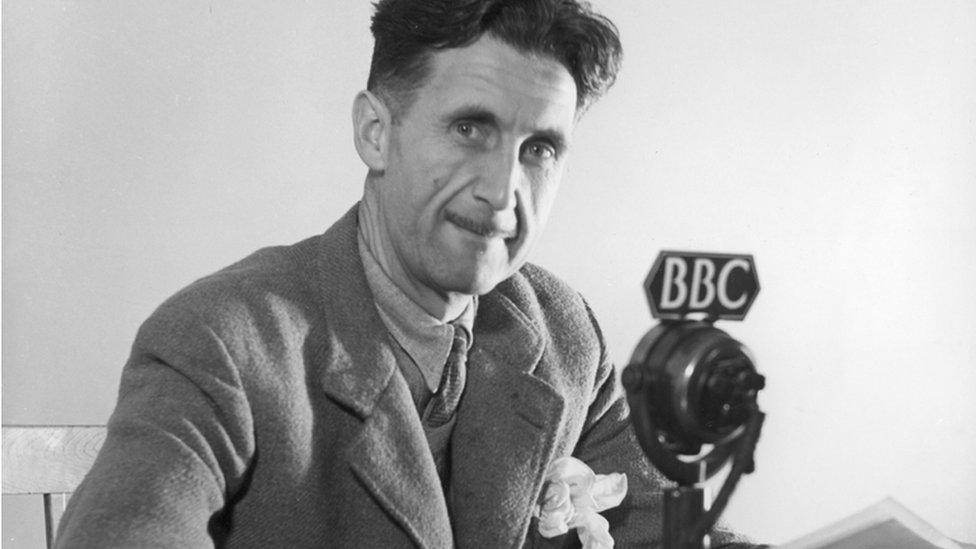

The Scottish island where George Orwell created 1984

- Published

George Orwell escaped to a remote Scottish island to create his final masterpiece - the dystopian classic 1984.

Going into the Corryvreckan whirlpool is a heart-stopping experience even when conditions are relatively benign.

It hits quite suddenly as you are passing through the narrow stretch of sea between the islands of Jura and Scarba.

One side of the boat drops away and you find yourself sitting on the deck.

Then the other side goes and you are grabbing on to the guard rail to stop yourself sliding in the opposite direction.

Orwell's boat got into trouble in Corryvecken on the way back from a picnic

It must have felt something like this when George Orwell found himself in the throws of the Corry on the way back from a picnic on the west side of Jura.

But for him, it was so much worse than being knocked about a bit.

The outboard motor was wrenched off and his young nephew, Henry, attempted to row them towards a rocky islet of Eilean Mor.

As they got close, the boat capsized.

Orwell emerged from underneath it and managed to drag himself and his young son on to the rocks.

He and his companions had been extremely lucky.

After that it was just a question of waiting until a passing fisherman spotted them and took them home, shaken, no doubt, but unharmed.

Orwell dragged himself and his son on to the rocky islet of Eilean Mor

I have come to Jura to walk in Orwell's footsteps on this beautiful Hebridean island, which lies off the Argyll coast.

He was here to escape the daily grind of journalism and to find a clean environment which doctors thought would help him recover from a dangerous bout of tuberculosis.

But what did he find here and did the island lifestyle have any impact on the masterpiece he was to create - 1984?

The road to Barnhill

The ferryman, Duncan Phillips, ties up at what he describes as a pier, but which is in fact just a big lump of concrete with an old rusting ladder driven into it.

He points to a track leading over rising ground to the south and tells me Barnhill is about half an hour in that direction.

I set off up the track, the sea on my left, a sloping hillside full of old oaks and other native species on the other.

All I can hear is the trickle of water in the burn alongside the track and birdsong from the trees beyond.

Barnhill is on the east side of the island

At the top of the hill, Barnhill comes into view in a hollow of land on the east side of the island.

Behind it is the Sound of Jura stretching away towards the hazy coastline of Argyll.

Relics from the past

Rob and Scofie Fletcher, who own the house, are expecting me.

The kettle goes on the Aga and I ask if there are any relics in the house from the time that Orwell lived here with his young adopted son, Richard.

Rob knows the history of the house because it was his grandparents who rented it to Orwell back in the 1940s.

He thinks for a minute and then suggests we take a look at the bath upstairs.

The bath at Barnhill is the same one Orwell used

It's a solid cast iron affair with big claw feet and deep, deep stains from the peaty water delivered by the house's private supply.

We stand for a moment imagining the famous author marinating in the bath like a steaming cup of strong tea.

Battering out the novel

Down the corridor is Orwell's bedroom.

It was here that he completed the manuscript for 1984.

He had been unable to get a typist to the island to batter out a fair copy of the novel for his publisher.

So he had to do it himself.

Sitting in bed, powered by cups of tea, hand-rolled cigarettes and perhaps the occasional mug of gin.

Hard place

Rob runs his finger across the wall above the bed.

It is damp with condensation.

He says: "If you're staying here in the wintertime and there's condensation running down the walls and you're just trying to get by on a daily basis and feed yourself and look after your family and look after your children, it seems like a hard enough place to operate.

"But if you throw in trying to write a very important book, I really don't understand how he managed to combine all those things. And managed to get the book finished when he was terminally ill."

It is a sobering thought. That this classic of dystopian literature actually killed the man who wrote it in these beautiful but harsh surroundings.

Orwell's adopted son, Richard Blair, doesn't remember it quite like that.

He was just turning two when he arrived on the island in 1946.

I spoke to him at his home in Warwickshire and asked him what were his strongest impressions of his father from that time.

"First of all of course, smoking," he says.

"The clickety-click of his typewriter in the bedroom.

"He would get up, have breakfast, then he would go to his bedroom, and he would write or type for the morning.

"He would then come down and have lunch with us.

"His voice was quite weak and slightly high-pitched.

"But that of course was the consequence of being shot through the neck in Spain. And he had this incessant cough which he'd had since childhood."

In January 1949, Orwell's condition had worsened so much, it was decided that he needed treatment on the mainland.

But as Orwell's sister, Avril, drove them down the rough track to the ferry, one of the big old saloon's tyres blew out.

Richard and his father were left in the car while Avril and a family friend, Bill Dunn, walked back to Barnhill to organise a repair.

Richard says: "We were just sitting there as you can imagine on a dark afternoon in wintertime, in January, and to while away the time he would tell me little stories.

"I think he probably made the stories up as he went along. I remember being given a sweet of some sort. And there we sat and waited for them to come and fix the car and we went on down to Ardlussa where I think he spent the night."

Orwell's death

These were the last moments that Richard spent with his father on the island.

He and Avril and Bill stayed on Jura through the rest of 1949.

He was taken to see Orwell in a sanatorium in the Gloucestershire later that year.

But he was back on Jura when his father's death was an item in the 8 o'clock news on the Home Service.

I asked Richard Blair if he thought Orwell's experience of Jura influenced the book which he eventually produced.

He told me that the tranquillity of the island did enable him to focus on his work in a way that would not have been possible in London.

Orwell himself said in his letters that he might have written a better book if he had not been so unwell.

Perhaps the simple fact is that Jura was only a brief respite from the ill health that was inevitably going to kill him.

But it was a respite which gave him just enough time to write the book he'd been planning for several years.

1984 did not end up as a great unfinished last work.

It was an accomplished masterpiece of story-telling and propaganda against totalitarianism.

Despite the hardship and the death of his father, Richard Blair's memories are of the freedom and happiness he felt living on Jura and exploring the island.

Seventy years later, he describes it as his spiritual home.

And whenever his own life comes to an end, he wants his ashes scattered on the Gulf of Corryvreckan.

He tells me with a smile: "Corryvreckan will finally get its due one day."