'There is hope for compulsive hoarders'

- Published

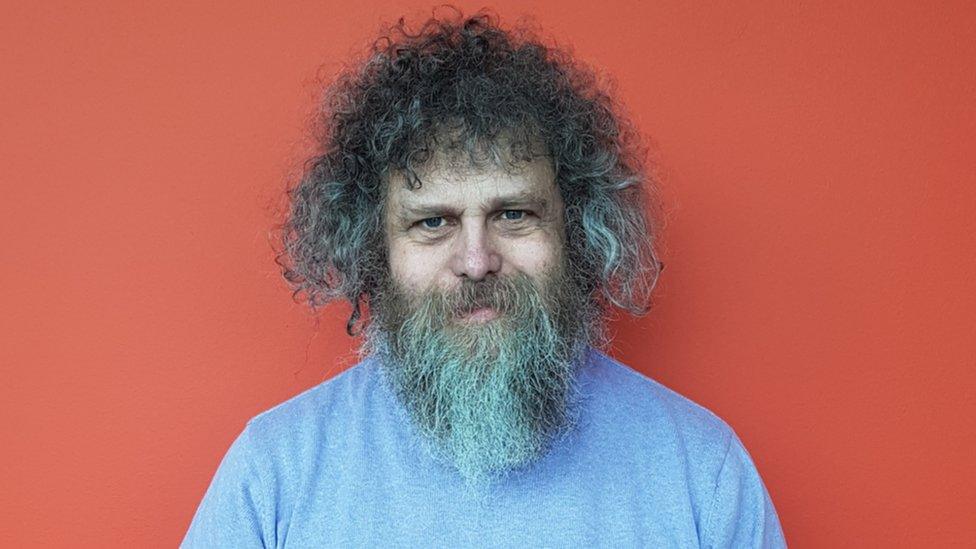

David Woods has a weakness for books, magazines and DVDs. Until recently the rooms in his home in Edinburgh were filled-to-bursting with a collection he had amassed over many years.

But David is not a collector - he has a problem with compulsive hoarding.

It became so bad that the clutter in his hallway made it difficult to get through his front door, and a "big mountain of stuff" in his bedroom meant he couldn't get to his bed.

Now, with the help of Linda Fay, of cluttering and hoarding specialists LifePod, David's home has become a much safer place to live.

She told BBC Radio Scotland's Kaye Adams' programme that David was struggling with day-to-day life until he began working with LifePod.

"In David's bedroom there was no floor space, you couldn't get to his bed, she said. "There was a big mountain of stuff in the middle of his room. I say stuff - it was books, magazines, DVDs.

"Even in the hallway, trying to get in the front door is difficult because you are manoeuvring round stuff."

And she said one support worker had been a regular visitor to the home for more than a year before she realised he had a fire place in his living room.

"Just moving around the house was difficult," she added.

David said he hoarded possessions to "fill a void" and it was a difficult habit to kick.

'Childish approach'

He admitted that he didn't even read many of the volumes he collected. "It's very difficult to know what to start with because there's so much stuff," he said.

"What am I going to read? What if I read the wrong thing? It's choices. There's a thing inherent in people that hoard that their brain doesn't work very well with making decisions or choices."

But it took a long time for him to admit that he had a problem.

"I don't think I realised it till after we'd been working with LifePod strangely enough," he said. "Even until that point I was quite recalcitrant. I was thinking I was perfectly normal to have so much stuff.

"If... I was somebody who had who had a big house and a lot of money, because of the books that I have, I would be seen as an eccentric. Because I don't have a big house or a lot of money, I'm seen as being mad. There's a difference between the two things.

"I think I still denied it until about six months in and we worked for three years.

"And there are still occasions when I go 'Oh, what's the problem? Why can't I have this stuff?' It's a very childish approach to things."

What is hoarding disorder?

Hoarding disorder is defined as the urge to acquire unusually large amounts of possessions and an inability to get rid of those possessions - even when they have no practical usefulness or monetary value.

According to the NHS, someone with a hoarding disorder might:

Keep or collect items that may have little or no monetary value, such as junk mail and carrier bags, or items they intend to reuse or repair

Find it hard to categorise or organise items

Have difficulties making decisions

Struggle to manage everyday tasks, such as cooking, cleaning and paying bills

Become extremely attached to items, refusing to let anyone touch or borrow them

Have poor relationships with family or friends

LifePod helped David to reduce his hoard, and to re-organise the possessions he wanted to keep.

He said: "I look through stuff and think why have I got this huge text book from 1972 about microbiology? Oh yeah, I was going to do some art work with it. Yeah, right, really?

"Because that's the other problem, it's really easy for someone who's a hoarder to justify everything and you have to take a step back."

The microbiology book was thrown out.

He said he felt a "lightening" after removing the clutter from his home - like a burden had been lifted.

Both his kitchen and bathroom are now clear, his living room is "half-clear" and he can now get into his bed.

But he admitted that it was at times a difficult process.

'Message of hope'

"There may well have been swearing, I may well have thrown people out of the house," he said.

But it has taken much more than a big spring clean to tackle David's hoarding problem.

LifePod's Linda Fay said: "Hoarding is a chronic illness so you're not going to cure it overnight, you're probably not going to cure it at all.

"It's learning to develop strategies and techniques to make it easier for people.

"Our focus is always on making people safer at home and relatively more comfortable. It's not about getting rid of all the stuff."

There can be a positive outlook for people who hoard, said David.

"The message is that there's hope for people to deal with the problem, as long as there's patience and compassion put into place."

Details of organisations offering information and support with mental health are available here, or you can call for free, at any time to hear recorded information on 08000 564 756.

- Published23 April 2018